- The Open University

- Accessibility hub

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

About this free course

Become an ou student, download this course, share this free course.

Start this free course now. Just create an account and sign in. Enrol and complete the course for a free statement of participation or digital badge if available.

4 The importance of critical thinking and analysis in academic studies

The aim of critical thinking is to try to maintain an objective position. When you think critically, you weigh up all sides of an argument and evaluate its strengths and weaknesses. So, critical thinking entails: actively seeking all sides of an argument, testing the soundness of the claims made, as well as testing the soundness of the evidence used to support the claims.

Box 1 What ‘being critical’ means in the context of critical thinking

Critical thinking is not :

- restating a claim that has been made

- describing an event

- challenging peoples’ worth as you engage with their work

- criticising someone or what they do (which is made from a personal, judgemental position).

Critical thinking and analysis are vital aspects of your academic life – when reading, when writing and working with other students.

While critical analysis requires you to examine ideas, evaluate them against what you already know and make decisions about their merit, critical reflection requires you to synthesise different perspectives (whether from other people or literature) to help explain, justify or challenge what you have encountered in your own or other people’s practice. It may be that theory or literature gives us an alternative perspective that we should consider; it may provide evidence to support our views or practices, or it may explicitly challenge them.

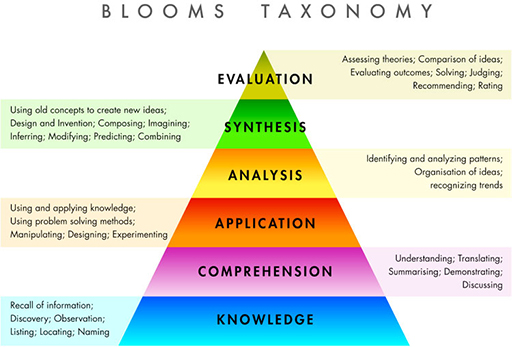

You will encounter a number of activities and assignments in your postgraduate studies that frequently demand interpretation and synthesis skills. We introduced such an activity in Session 1 (Activity 3). Part of this requires use of ‘higher-order thinking skills’, which are the skills used to analyse and manipulate information (rather than just memorise it). In the 1950s, Benjamin Bloom identified a set of important study and thinking skills for university students, which he called the ‘thinking triangle’ (Bloom, 1956) (Figure 1). Bloom’s taxonomy can provide a useful way of conceptualising higher-order thinking and learning. The six intellectual domains, their descriptions and associated keywords are outlined in Table 1.

This figure shows a pyramid with the following words, from top to bottom: evaluation (assessing theories; comparison of ideas; evaluating outcomes; solving; judging; recommending; rating), synthesis (using old concepts to create new ideas; design and invention; composing; imagining; inferring; modifying; predicting; combining), analysis (identifying and analysing patterns; organisation of ideas; recognising trends), application (using and applying knowledge; using problem solving methods; manipulating; designing; experimenting), comprehension (understanding; translating; summarising; demonstrating; discussing), knowledge (recall of information; discovery; observation; listing; locating; naming).

- Onsite training

3,000,000+ delegates

15,000+ clients

1,000+ locations

- KnowledgePass

- Log a ticket

01344203999 Available 24/7

What is Critical Reading? A Comprehensive Guide

Critical Reading refers to the process of actively analysing, questioning, and evaluating a text to understand its deeper meaning, and assess its credibility. This blog explores the art of Critical Reading, delving into the essential steps, invaluable tips and numerous benefits. Continue reading to learn more!

Exclusive 40% OFF

Training Outcomes Within Your Budget!

We ensure quality, budget-alignment, and timely delivery by our expert instructors.

Share this Resource

- Creative Writing Course

- Report Writing Course

- Attention Management Training

- English Grammar Course

In today’s world, where information is abundant, and opinions are everywhere, distinguishing truth from noise is crucial. The key to this is Critical Reading—a skill that goes beyond just skimming through text. It’s about questioning every claim and understanding the deeper message behind the words.

Whether you’re tackling complex academic papers or everyday news, mastering Critical Reading helps you think independently and stay sharp. This blog explores the secrets of effective Critical Reading, highlighting its benefits and offering essential tips. Dive in and transform how you engage with the written word.

Table of Contents

1) What is Critical Reading?

2) The Importance of Critical Analysis

3) Key Steps in Critical Reading

4) Tips to Develop Critical Reading Skills

5) Advantages of Critical Reading

6) Critical Reading Tools

7) Conclusion

What is Critical Reading?

Critical Reading, also known as critical analysis, is the careful reading of a text by asking yourself functional questions to understand and assess the text's merits comprehensively. Analysing texts and finding answers to these questions enables you to gain clarity of what you're reading.

The ability to read critically is a skill that most people develop throughout their lives by examining pieces of text to determine the key ideas they represent. The main purpose of Critical Reading is to focus on these three elements:

1) What the author says

2) What the text describes

3) How the reader would interpret the text

The Importance of Critical Analysis

The ability to read critically is helpful in a diverse range of jobs and can even significantly improve how one processes information outside of work. As you hone this skill, it's easier to determine what the author is expressing in their research or literary work and understand their viewpoint.

Additionally, it enables you to harness your own outlook to come up with accurate and logical arguments for and against the author's viewpoint. We will explore the specific benefits of Critical Reading later in this blog

Key Steps in Critical Reading

Now that you better understand the importance of Critical Reading, it's time to explore the "how." Critical Reading is an active process that necessitates a fair amount of effort but also needs a good structure for the best results. Here are the essential steps to consider:

1) Determine the Text's Recipient: One of the first steps in critical analysis is determining the target recipient. Some authors address their works to the public, such as when writing a novel. Other times, they may write for a highly specific audience, for example, when creating manuals or industry reports. By looking into the author's intention and potential audience, you can better understand the purpose of the text you are evaluating.

2) Read Normally: On the first read, go through a couple of paragraphs to get a general feel for the topic and core idea. This will prepare you for the next step.

3) Read Again With Deeper Focus: Carefully read each sentence, with the goal of understanding the main concepts and attention to details. Don't hesitate to repeat this step until you feel ready to move forward.

4) Take Notes: Note down the important aspects of the text and any specific detail that stand out. Write down any questions you feel you might answer later.

5) Understand Every Word for Context: Look up unfamiliar words and research any technical concepts or historical events mentioned in the text to understand the context better.

6) Analyse the Purpose of the Words: Pay attention to the kind of words being used. Put yourself in the author's shoes and imagine why those particular words are being used to express these ideas. Is the author trying to persuade you to believe in a concept or philosophy, or are they just trying to entertain you?

7) Practice Metacognition: Challenge the author's ideas and concepts and decide why you agree or disagree with the author's point. Try to imagine a better way for the writer to present those ideas. This can include pointing out inconsistencies or providing additional materials supporting the author's claims.

8) Come to Your Conclusions: Once you are comfortable with the mental process by which you filtered all the information, decide:

a) Whether that particular text was to your liking

b) Whether you enjoyed reading and analysing it

c) What you learned

d) How much do you agree with the writer's ideas and how they expressed them?

Acquaint yourself with comprehension, techniques, and problems of reading in our Speed Reading Course - Sign up now!

Tips to Develop Critical Reading Skills

Once you are acquainted with the crucial steps to perform a Critical Reading, you may need some tips to develop Critical Reading skills. These tips will ensure you don’t feel overwhelmed by complex arguments and engage with the content thoughtfully

Define a Purpose for Reading

Before reading a text, establish your purpose. Whether your objective is to gain a general understanding, extract specific information, or critically analyse the content, clarifying the objective sets the stage for effective Critical Reading.

Preview the Material

Start by previewing the text to get a firm handle on its structure, headings, and key points. This initial scan builds a roadmap, providing insights into the author’s organisation and core ideas. Also, pay special attention to introductory and concluding paragraphs for any overarching themes.

Ask Questions and Predict

Based on your preview, formulate questions about the text. These questions could include:

a) What is the author’s main argument?

b) Are there biases or assumptions?

Engaging in predictive thinking is important as it helps anticipate the author’s next moves.

Read Actively and Annotate

Make annotations as you progress through the text. Highlight critical phrases, note down questions, and record your reactions. Annotation transforms the reading process into a dynamic dialogue which facilitates later review.

Identify the Main Idea

Find out the central theme of the text. Recognising the author's primary message provides a focal point for understanding supporting details and assessing the author’s argument.

Assess Source Credibility

You can assess the source's reliability by considering the publication’s reputation, the author’s qualifications, and potential biases. Critical Reading involves discerning what is said, who is saying it, and why. This step ensures you are dealing with trustworthy information.

Make Connections

Connect the text to your existing experiences and knowledge. Try to draw parallels to personal experiences and recognise discipline patterns. Making connections contributes to a holistic understanding of the text.

Reflect and Summarise

Pause periodically to reflect on the material. You can summarise key points and assess the text's overall impact. Reflection reinforces your understanding and allows for deeper engagement with the content.

Engage in Criticism

Critical analysis evaluates the material's strengths, weaknesses, and broader implications. It asks questions about the author’s assumptions, considers alternative viewpoints, and evaluates the soundness of the arguments presented.

Synthesise Information

Synthesise the information derived from the text with your existing knowledge. This step involves:

a) Integrating fresh insights into your mental framework

b) Developing a cohesive understanding of the subject matter

This is the culmination of Critical Reading, turning information into knowledge.

Advantages of Critical Reading

Critical Reading plays a key role in reader development and boasts many benefits. Although reading simply for pleasure is rewarding, Critical Reading takes things to new heights. Let's explore the main advantages of practising critical analysis:

1) Better Communication: Depending on your profession and role, written communication may be necessary for your team's success. Critical Reading can help you understand colleagues' suggestions and evaluate their ideas' potential. This can substantially improve your collaborative work, especially with a remote team that rarely conducts in-person meetings.

2) Better Logical and Problem-solving Skills: Critical Reading encourages you to actively reflect on a text's meaning and evaluate it in the context of your profession. You can improve your problem-solving and logical thinking skills by gaining a deeper understanding of the problem and its surroundings. Consequently, you may require less time to find innovative solutions to any workplace challenges.

3) Better Memory: Putting extensive thought into a text helps you memorise more details from what you have read. This is possible because assessing written information using specific criteria creates unique connections in your memory. Additionally, it can make it easier to instantly recall facts and even statistics, which can be handy in case you are preparing for a professional assessment or public speech.

4) Overall Mental Development: Critical Reading involves regular use of judgment and logic to make accurate and realistic conclusions. This can directly impact the development of your other skills, such as critical thinking, which is an extension of critical analysis. The combination of these abilities can serve as an effective foundation to facilitate any learning efforts and improve your overall mental development.

Master your skills for data synthesis and impactful storytelling in our comprehensive Report Writing Course – Register now!

Critical Reading Tools

Critical Reading is quite complex and can be time-consuming. But with the right strategies and tools, it can become much easier over time. Reading tracking apps such as Goodreads and Bookly can make the Critical Reading process more effective and less intimidating. These apps help readers keep track of their reading habits.

Additionally, in the context of a classroom where Critical Reading is of utmost importance, there are several tools available to ease the process:

1) Pre-reading Tools: Students must activate their prior knowledge before diving into a text and set a purpose for reading. Teachers can use platforms such as Padlet or Jamboard to create digital boards where students can post questions related to the topic.

2) During-reading Tools: Teachers can use tools such as Google Docs or Kami to create editable text versions, allowing students to highlight, comment, or insert notes.

3) Post-reading Tools: After reading a text, students need to summarise, synthesise, and evaluate what they have learned. Teachers can utilise tools such as Book Creator or Adobe Spark to create multimedia presentations or digital books that showcase the students' understanding and analysis of the text.

4) Collaborative Reading Tools: Critical Reading is not necessarily an individual skill; it can also be social. Tools such as Google Classroom or Seesaw can help teachers create online spaces where students can post their work, comment on other's posts, and offer and receive feedback.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Critical Reading is an empowering skill that increases one's ability to engage with texts on a deeper level. By questioning, analysing, and synthesising information, you can not only improve comprehension but also become a more informed thinker, capable of navigating the intricacies of the written word with confidence and deeper insight.

Are you facing creative writing challenges? Handle these challenges with ease in our Creative Writing Course - Sign up now!

Frequently Asked Questions

The primary purpose of Critical Reading is to engage deeply with a text in order to understand its meaning, assess its arguments, and evaluate its validity.

The three C’s of critical thinking are curiosity, creativity and criticism.

The Knowledge Academy takes global learning to new heights, offering over 30,000 online courses across 490+ locations in 220 countries. This expansive reach ensures accessibility and convenience for learners worldwide.

Alongside our diverse Online Course Catalogue, encompassing 19 major categories, we go the extra mile by providing a plethora of free educational Online Resources like News updates, Blogs , videos, webinars, and interview questions. Tailoring learning experiences further, professionals can maximise value with customisable Course Bundles of TKA .

The Knowledge Academy’s Knowledge Pass , a prepaid voucher, adds another layer of flexibility, allowing course bookings over a 12-month period. Join us on a journey where education knows no bounds.

The Knowledge Academy offers various Personal Development Courses , including the Creative Writing Course and the Speed Writing Course. These courses cater to different skill levels, providing comprehensive insights into 8 Powerful Tips and Techniques for Persuasive Writing .

Our Business Skills Blogs cover a range of topics related to critical analysis, offering valuable resources, best practices, and industry insights. Whether you are a beginner or looking to advance your Critical Reading skills, The Knowledge Academy's diverse courses and informative blogs have got you covered.

Upcoming Business Skills Resources Batches & Dates

Fri 20th Dec 2024

Fri 3rd Jan 2025

Fri 7th Mar 2025

Fri 2nd May 2025

Fri 4th Jul 2025

Fri 5th Sep 2025

Fri 7th Nov 2025

Get A Quote

WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

My employer

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry

- Business Analysis

- Lean Six Sigma Certification

Share this course

Biggest christmas sale.

We cannot process your enquiry without contacting you, please tick to confirm your consent to us for contacting you about your enquiry.

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry.

We may not have the course you’re looking for. If you enquire or give us a call on 01344203999 and speak to our training experts, we may still be able to help with your training requirements.

Or select from our popular topics

- ITIL® Certification

- Scrum Certification

- ISO 9001 Certification

- Change Management Certification

- Microsoft Azure Certification

- Microsoft Excel Courses

- Explore more courses

Press esc to close

Fill out your contact details below and our training experts will be in touch.

Fill out your contact details below

Thank you for your enquiry!

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go over your training requirements.

Back to Course Information

Fill out your contact details below so we can get in touch with you regarding your training requirements.

* WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

Preferred Contact Method

No preference

Back to course information

Fill out your training details below

Fill out your training details below so we have a better idea of what your training requirements are.

HOW MANY DELEGATES NEED TRAINING?

HOW DO YOU WANT THE COURSE DELIVERED?

Online Instructor-led

Online Self-paced

WHEN WOULD YOU LIKE TO TAKE THIS COURSE?

Next 2 - 4 months

WHAT IS YOUR REASON FOR ENQUIRING?

Looking for some information

Looking for a discount

I want to book but have questions

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go overy your training requirements.

Your privacy & cookies!

Like many websites we use cookies. We care about your data and experience, so to give you the best possible experience using our site, we store a very limited amount of your data. Continuing to use this site or clicking “Accept & close” means that you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about our privacy policy and cookie policy cookie policy .

We use cookies that are essential for our site to work. Please visit our cookie policy for more information. To accept all cookies click 'Accept & close'.

- Reading to Engage and Evaluate

- Effective Critical Reading

Audience and Purpose

Analysis Checklist

- Reading for Evaluation

As an effective critical reader you must be able to identify the important elements of a text and their function.

To analyze means to break a text down into its parts to better understand it. When analyzing you notice both what the author is saying and how they are saying it. Looking deeply into a text beyond the explicit information can tell you the intended audience, the author's agenda or purpose, and the argument. Clues about these areas are often found in the language the author uses such as the word choice, phrasing, and tone.

Look at this excerpt. Click each number button to learn more about evaluating this text:

How Is Asthma Treated?

Take your medicine exactly as your doctor tells you and stay away from things that can trigger an attack to control your asthma.

Everyone with asthma does not take the same medicine.

You can breathe in some medicines and take other medicines as a pill. Asthma medicines come in two types-quick-relief and long-term control. Quick-relief medicines control the symptoms of an asthma attack. If you need to use your quick-relief medicines more and more, visit your doctor to see if you need a different medicine. Long-term control medicines help you have fewer and milder attacks, but they don't help you while you are having an asthma attack.

Asthma medicines can have side effects, but most side effects are mild and soon go away. Ask your doctor about the side effects of your medicines.

Remember -you can control your asthma. With your doctor's help, make your own asthma action plan. Decide who should have a copy of your plan and where he or she should keep it. Take your long-term control medicine even when you don't have symptoms. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC), 2018).

Use of Second Person

The author uses the second person point of view, the "you" pronoun to address the reader. The use of second person point of view is informal and not often seen as scholarly writing.

Scholarly Voice

The author uses contractions like don't and avoids medical terminology and difficult vocabulary.

Talking Directly to Readers

The author seems to be talking directly to readers who are not in the medical profession, giving them advice on how to treat asthma and prevent attacks.

From this analysis we can interpret that the intended audience is individuals with asthma.

The tone, while informal, it is also authoritative and direct. Note and gentle, emotional, or anecdotal information that is included. The author does not highlight statistics about the high rate of asthma or the implications of leaving it untreated. In order to persuade, the writing is presented in an objective manner that supports awareness. From this analysis, we understand that the author's purpose is to inform in a very practical way.

Why does analyzing for audience and purpose matter?

The audience and purpose can tell you whether a source might be appropriate to use in your own research and writing.

For example, because this excerpt was written to inform the general public about asthma, it does not have the level of detail and evidence necessary for scholarly research.

It is also helpful to know from what point of view the author is writing so you can consider that when evaluating for potential bias. Another benefit of analyzing in this way is that you can apply what you learn to your own writing. For example, when reading an academic essay you may identify that word choice and tone are really effective in communicating with the academic community. You can then try a similar voice and tone in your own writing.

If you find it helpful to follow checklists, consider using this one to practice your analysis skills as you are reading.

Who is the intended audience?

What is the author's purpose?

How do the audience and purpose influence your reading?

Argument and Evidence

What is the thesis?

What are the main points that support that thesis, and how do those main points connect?

What evidence is used?

Language and Tone

What is the tone the author uses?

How does the author's use of language and tone support the audience, purpose, and argument?

- Previous Page: Reading to Engage and Evaluate

- Next Page: Reading for Evaluation

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Certification, Licensure and Compliance

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- Subject Guides

Being critical: a practical guide

Critical reading.

- Being critical

- Critical thinking

- Evaluating information

- Reading academic articles

- Critical writing

The purposes and practices of reading

The way we read depends on what we’re reading and why we’re reading it. The way we read a novel is different to the way we read a menu . Perhaps we are reading to understand a subject, to increase our knowledge, to analyse data, to retrieve information, or maybe even to have fun! The purpose of our reading will determine the approach we take.

Reading for information

Suppose we were trying to find some directions or opening hours... We would need to scan the text for key words or phrases that answer our question, and then we would move on.

It's a bit like doing a Google search and then just reading the results page rather than accessing the website.

Reading for understanding

When we're reading for pleasure or doing background reading on a topic, we'll generally read the text once, from start to finish . We might apply skimming techniques to look through the text quickly and get the general gist. Our engagement with the text might therefore be quite passive: we're looking for a general understanding of what's being written, perhaps only taking in the bits that seem important.

Reading for analysis

When we're doing reading for an essay, dissertation, or thesis, we're going to need to actively read the text multiple times . All the while we'll engage our prior knowledge and actively apply it to our reading, asking questions of what's been written.

This is critical reading !

Reading strategies

When you’re reading you don’t have to read everything with the same amount of care and attention. Sometimes you need to be able to read a text very quickly.

There are three different techniques for reading:

- Scanning — looking over material quite quickly in order to pick out specific information;

- Skimming — reading something fairly quickly to get the general idea;

- Close reading — reading something in detail.

You'll need to use a combination of these methods when you are reading an academic text: generally, you would scan to determine the scope and relevance of the piece, skim to pick out the key facts and the parts to explore further, then read more closely to understand in more detail and think critically about what is being written.

These strategies are part of your filtering strategy before deciding what to read in more depth. They will save you time in the long run as they will help you focus your time on the most relevant texts!

You might scan when you are...

- ...browsing a database for texts on a specific topic;

- ...looking for a specific word or phrase in a text;

- ...determining the relevance of an article;

- ...looking back over material to check something;

- ...first looking at an article to get an idea of its shape.

Scan-reading essentially means that you know what you are looking for. You identify the chapters or sections most relevant to you and ignore the rest. You're scanning for pieces of information that will give you a general impression of it rather than trying to understand its detailed arguments.

You're mostly on the look-out for any relevant words or phrases that will help you answer whatever task you're working on. For instance, can you spot the word "orange" in the following paragraph?

Being able to spot a word by sight is a useful skill, but it's not always straightforward. Fortunately there are things to help you. A book might have an index, which might at least get you to the right page. An electronic text will let you search for a specific word or phrase. But context will also help. It might be that the word you're looking for is surrounded by similar words, or a range of words associated with that one. I might be looking for something about colour, and see reference to pigment, light, or spectra, or specific colours being called out, like red or green. I might be looking for something about fruit and come across a sentence talking about apples, grapes and plums. Try to keep this broader context in mind as you scan the page. That way, you're never really just going to be looking for a single word or orange on its own. There will normally be other clues to follow to help guide your eye.

Approaches to scanning articles:

- Make a note of any questions you might want to answer – this will help you focus;

- Pick out any relevant information from the title and abstract – Does it look like it relates to what you're wanting? If so, carry on...

- Flick or scroll through the article to get an understanding of its structure (the headings in the article will help you with this) – Where are certain topics covered?

- Scan the text for any facts , illustrations , figures , or discussion points that may be relevant – Which parts do you need to read more carefully? Which can be read quickly?

- Look out for specific key words . You can search an electronic text for key words and phrases using Ctrl+F / Cmd+F. If your text is a book, there might even be an index to consult. In either case, clumps of results could indicate an area where that topic is being discussed at length.

Once you've scanned a text you might feel able to reject it as irrelevant, or you may need to skim-read it to get more information.

You might skim when you are...

- ...jumping to specific parts such as the introduction or conclusion;

- ...going over the whole text fairly quickly without reading every word;

Skim-reading, or speed-reading, is about reading superficially to get a gist rather than a deep understanding. You're looking to get a feel for the content and the way the topic is being discussed.

Skim-reading is easier to do if the text is in a language that's very familiar to you, because you will have more of an awareness of the conventions being employed and the parts of speech and writing that you can gloss over. Not only will there be whole sections of a text that you can pretty-much ignore, but also whole sections of paragraphs. For instance, the important sentence in this paragraph is the one right here where I announce that the important part of the paragraph might just be one sentence somewhere in the middle. The rest of the paragraph could just be a framework to hang around this point in order to stop the article from just being a list.

However, it may more often be that the important point for your purposes comes at the start of the paragraph. Very often a paragraph will declare what it's going to be about early on, and will then start to go into more detail. Maybe you'll want to do some closer reading of that detail, or maybe you won't. If the first paragraph makes it clear that this paragraph isn't going to be of much use to you, then you can probably just stop reading it. Or maybe the paragraph meanders and heads down a different route at some point in the middle. But if that's the case then it will probably end up summarising that second point towards the end of the paragraph. You might therefore want to skim-read the last sentence of a paragraph too, just in case it offers up any pithy conclusions, or indicates anything else that might've been covered in the paragraph!

For example, this paragraph is just about the 1980s TV gameshow "Treasure Hunt", which is something completely irrelevant to the topic of how to read an article. "Treasure Hunt" saw two members of the public (aided by TV newsreader Kenneth Kendall) using a library of books and tourist brochures to solve a series of five clues (provided, for the most part, by TV weather presenter Wincey Willis). These clues would generally be hidden at various tourist attractions within a specific county of the British Isles. The contestants would be in radio contact with a 'skyrunner' (Anneka Rice) who had a map and the use of a helicopter (piloted by Keith Thompson). Solving a clue would give the contestants the information they needed to direct the skyrunner (and her crew of camera operator Graham Berry and video engineer Frank Meyburgh) to the location of the next clue, and, ultimately, to the 'treasure' (a token object such as a little silver brooch). All of this was done against the clock, the contestants having only 45' to solve the clues and find the treasure. This, necessarily, required the contestants to be able to find relevant information quickly: they would have to select the right book from the shelves, and then navigate that text to find the information they needed. This, inevitably, involved a considerable amount of skim-reading. So maybe this paragraph was slightly relevant after all? No, probably not...

Skim-reading, then, is all about picking out the bits of a text that look like they need to be read, and ignoring other bits. It's about understanding the structure of a sentence or paragraph, and knowing where the important words like the verbs and nouns might be. You'll need to take in and consider the meaning of the text without reading every single word...

Approaches to skim-reading articles:

- Pick out the most relevant information from the title and abstract – What type of article is it? What are the concepts? What are the findings?;

- Scan through the article and note the headings to get an understanding of structure;

- Look more closely at the illustrations or figures ;

- Read the conclusion ;

- Read the first and last sentences in a paragraph to see whether the rest is worth reading.

After skimming, you may still decide to reject the text, or you may identify sections to read in more detail.

Close reading

You might read closely when you are...

- ...doing background reading;

- ...trying to get into a new or difficult topic;

- ...examining the discussions or data presented;

- ...following the details or the argument.

Again, close reading isn't necessarily about reading every single word of the text, but it is about reading deeply within specific sections of it to find the meaning of what the author is trying to convey. There will be parts that you will need to read more than once, as you'll need to consider the text in great detail in order to properly take in and assess what has been written.

Approaches to the close reading of articles:

- Focus on particular passages or a section of the text as a whole and read all of its content – your aim is to identify all the features of the text;

- Make notes and annotate the text as you read – note significant information and questions raised by the text;

- Re-read sections to improve understanding;

- Look up any concepts or terms that you don’t understand.

Questioning

Questioning goes hand-in-hand with reading for analysis. Before you begin to read, you should have a question or set of questions that will guide you. This will give purpose to your reading, and focus you; it will change your reading from a passive pursuit to an active one, and make it easier for you to retain the information you find. Think about what you want to achieve and keep the purpose in mind as you're reading.

Ask yourself...

- Why am I reading this? — What is my task or assignment question, and how is this source helping to answer it?

- What do I already know about the subject? — How can I relate what I'm reading to my own experiences?

You'll need to ask questions of the text too:

- Examine the evidence or arguments presented;

- Check out any influences on the evidence or arguments;

- Check the limitations of study design or focus;

- Examine the interpretations made.

Are you prepared to accept the authors’ arguments, opinions, or conclusions?

Critical reading: why, what, and how

Blocks to critical reading.

Certain habits or approaches we have to life can hold us back from really thinking objectively about issues. We may not realise it, but often we're our own worst enemies when it comes to being critical...

Select a student to reveal the statement they've made.

I have been asked to work on an area that is completely new. Where do I start in terms of finding relevant texts?

Ask for guidance:

ask your tutor or module leader

use your module reading lists

make use of the Skills Guides (oh... you are! Excellent!)

ask your Faculty Librarians

Take a look at our contextagon and begin to consider sources of information .

I don’t understand what I'm reading – It's too difficult!

If the text is difficult, don’t panic!

If it is a journal article, scan the text first – look at the contents, abstract, introduction, conclusion and subheadings to try to make sense of the argument.

Then read through the whole text to try to understand the key messages, rather than every single word or section. On a second reading, you will find it easier to understand more.

If you are struggling to get to grips with theories or concepts, you might find it useful to look at a summary as a way in -- for example, in an online subject encyclopaedia .

If you are struggling with difficult vocabulary, it may be useful to keep a glossary of key vocabulary, particularly if it is specialist or technical.

Remember, the more you read, the more you will understand it and be able to use it yourself.

Take a look at our Academic sources Skills Guide .

Help! There is too much to read and too little time!

University study involves a large amount of reading. However, some texts on your reading lists are core texts and some are more optional.

You will generally need to read the core text, but on the optional list there may be a range of texts which deal with the same topic from different perspectives. You will need to decide which are the most relevant to your interests and assignments.

Keep in mind the questions you want the text to answer and look for what is relevant to those questions. Prioritise and read only as much as you need to get the information you need (if it's a book, use the index; if it's an article, concentrate on the relevant parts).

Improve your note-taking skills by keeping them brief and selective.

If in doubt, ask your tutor or Faculty Librarians for guidance.

Take a look at the Organise and Analyse section of the Skills Guides.

I am struggling to remember what I have read.

To remember what you have read, you need to interact with the material. If you have questioned and evaluated the material you are reading, you will find it easier to remember.

Improve your active note-taking skills using a method like Cornell or Survey, Question, Read, Recite, Review (SQR3).

Annotate your pdfs and use a note-taking app .

Make time to consolidate your reading periodically. You could do this by summarising key points from memory or connecting ideas using mindmapping.

Consider using a reference management program to keep on top of reading, and mind-mapping software like Mindgenius to connect ideas.

Where did I read that thing?

Make sure you have a good system for taking notes and try to keep your notes organised/in one place, whether that is using an app or taking notes by hand. There is no right way to do this - find a system that works for you.

Logically label and file your notes, linking new information with what you already know and cross-reference with any handouts.

Make sure you make a note of information for referencing sources.

Where possible, save resources you have used to Google Drive or your University filestore , and organise these (e.g. by module, assessment, topic etc.).

Many of the above tips can be achieved with reference management software .

I have strong opinions about the argument being presented in the reading – why can’t I just put this side forward?

Truth is a complicated business. Core texts or texts by highly respected authors are an author’s interpretation, and that interpretation is not above question. Any single text only provides a perspective. Even a scientific observation may be modified by further evidence. Critical writing means making sure your argument is balanced, considering and critiquing a range of perspectives.

Read texts objectively and assess their value in terms of what they can bring to your work, rather than whether you agree with them or not.

If you agree or disagree strongly with an author, you still need to analyse their argument and justify why it is sound or unsound, reliable or unreliable, and valid or lacking validity.

Ignoring opposing views can be a mistake. Your reader may think you are unaware of the different views or are not willing to think the ideas through and challenge them.

Be careful not to be blinded by your own views about a topic or an author. Engaging actively with a text which you initially don’t agree with can mean you have to rethink or adjust your own position, making your final argument stronger.

Take a look at the other parts of the Being critical Skills Guides .

That's not right. Try again.

Being actively critical

Active reading is about making a conscious effort to understand and evaluate a text for its relevance to your studies. You would actively try to think about what the text is trying to say, for example by making notes or summaries.

Critical reading is about engaging with the text by asking questions rather than passively accepting what it says. Is the methodology sound? What was the purpose? Do ideas flow logically? Are arguments properly formulated? Is the evidence there to support what is being claimed?

When you're reading critically, you're looking to...

- ...link evidence to your own research;

- ...compare and contrast different sources effectively;

- ...focus research and sources;

- ...synthesise the information you've found;

- ...justify your own arguments with reference to other sources.

You're going beyond just an understanding of a text. You're asking questions of it; making judgements about it... What you're reading is no longer undisputed 'fact': it's an argument put forward by an author. And you need to determine whether that argument is a valid one.

"Reading without reflecting is like eating without digesting"

– Edmund Burke

"Feel free to reflect on the merits (or not) of that quote..."

– anon.

Critical reading involves understanding the content of the text as well as how the subject matter is developed...

- How true is what's being written?

- How significant are the statements that are being made?

Regardless of how objective, technical, or scientific the text may be, the authors will have made certain decisions during the writing process, and it is these decisions that we will need to examine.

Two models of critical reading

There are several approaches to critical reading. Here's a couple of models you might want to try:

Choose a chapter or article relevant to your assessment (or pick something from your reading list).

Then do the following:

Determine broadly what the text is about.

Look at the front and back covers

Scan the table of contents

Look at the title, headings, and subheadings

Read the abstract, introduction and conclusion

Are there any images, charts, data or graphs?

What are the questions the text will answer? Write some down.

Use the title, headings and subheadings to write questions

What questions do the abstract, introduction and conclusion prompt?

What do you already know about the topic? What do you need to know?

Do a first reading. Read selectively.

Read a section at a time

Answer your questions

Summarise or make brief notes

Underline or highlight any key points

Recite (in your own words)

Recall the key points.

Summarise key points from memory

Try to answer the questions you asked orally, without looking at the text or your notes

Use diagrams or mindmaps to recall the information

After you have completed the reading…

Go back over your notes and check they are clear

Check that you have answered all your questions

At a later date, review your notes to check that they make sense

At a later date, review the questions and see how much you can recall from memory

Choose a relevant article from your reading list and make brief notes on it using the prompts below.

Choose an article you have read earlier in your course and re-read it, applying the prompts below.

Compare your comments and the notes you have made. What are the differences?

Who is the text by? Who is the text aimed at? Who is described in the text?

What is the text about? What is the main point, problem or topic? What is the text's purpose?

Where is the problem/topic/issue situated?, and in what context?

When does the problem/topic/issue occur, and what is its context? When was the text written?

How did the topic/problem/issue occur? How does something work? How does one factor affect another? How does this fit into the bigger picture?

Why did the topic/problem/issue occur? Why was this argument/theory/solution used? Why not something else?

What if this or that factor were added/removed/altered? What if there are alternatives?

So what makes it significant? So what are the implications? So what makes it successful?

What next in terms of how and where else it's applied? What next in terms of what can be learnt? What next in terms of what needs doing now?

Here's a template for use with the model.

Go to File > Make a copy... to create your own version of the template that you can edit.

CC BY-NC-SA Learnhigher

Arguments & evidence

Academic reading can be a trial. In more ways than one...

It might help to think of every text you read as a witness in a court case. And you're the judge ! You're going to need to examine the testimony...

- What’s being claimed ?

- What are the reasons for making that claim?

- Are there gaps in the evidence?

- Do other witnesses support and corroborate their testimony?

- Does the testimony support the overall case ?

- How does the testimony relate to the other witnesses?

You're going to need to consider all sides of the case...

Considering the argument

An argument explains a position on something. A lot of academic writing is about gathering those claims and explaining your own position through their explanations.

You'll need to question...

- ...the author's claims ;

- ...the arguments they use — are their claims well documented ?;

- ...the counter-arguments presented;

- ...any bias in the source;

- ...the research method being used;

- ...how the author qualifies their arguments.

You'll also need to develop your own reasoned arguments, based on a logical interpretation of reliable sources of information.

What's the evidence?

Evidence isn't just the results of research or a reference to an academic study. You might use other authors' opinions to back up your argument. Keep in mind that some evidence is stronger than others:

You can get an idea of an author's certainty through the language they use, too:

Linking evidence to argument

- Why did the author select the evidence they did? — Why did they decide to use a particular methodology, choose a specific method, or conduct the work in the way they did?

- How does the author interpret the evidence?

- How does the evidence prove or help the argument?

Even in the most technical and scientific disciplines, the presentation of argument will always involve elements that can be examined and questioned. For example, you could ask:

- Why did the author select that particular topic of enquiry in the first place?

- Why did the author select that particular process of analysis?

Synthesis :

"the combination of components or elements to form a connected whole."

You'll need to make logical connections between the different sources you encounter, pulling together their findings. Are there any patterns that emerge?

Analyse the texts you've found, and how meaningful they are in context of your studies...

- How do they compare to each other and to any other knowledge you are gathering about the subject? Do some ideas complement or conflict with each other?

- How will you synthesise the different sources to serve an idea you are constructing? Are there any inferences you can draw from the material?

Embracing other perspectives

Good critical research seeks to be impartial, and will embrace (or, at the very least, address) conflicting opinions. Try to bring these into your research to show comprehensive searching and knowledge of the subject.

You can strengthen your argument by explaining, critically, why one source is more persuasive than another.

Recall & review

Synthesising research is much easier if you take notes. When you know an article is relevant to your area of research, read it and make notes which are relevant to you. Consider keeping a spreadsheet or something similar , to make a note of what you have read and how it relates to the task.

You don't need elaborate notes; just a summary of the relevant details. But you can use your notes to help with the process of analysing and synthesising the texts. One method you could try is the recall & review approach:

Try to summarise key words and elements of the text:

- Sketch a rough diagram of the text from memory — test what you can recall from your reading of the text;

- Make headings of the main ideas and note the supporting evidence;

- Include your evaluation — what were the strengths and weaknesses?

- Identify any gaps in your memory.

Go over your notes, focusing on the parts you found difficult. Organise your notes, re-read parts, and start to bring everything together...

- Summarise the text in preparation for writing;

- Be creative: use colour and arrows; make it easy to visualise;

- Highlight the ideas you may want to make use of;

- Identify areas for further research.

Critical analysis vs criticism

The aim of critical reading and critical writing is not to find fault; it's not about focusing on the negative or being derogatory. Rather it's about assessing the strength of the evidence and the argument. It's just as useful to conclude that a study or an article presents very strong evidence and a well-reasoned argument as it is to identify weak evidence and poorly formed arguments.

Criticising

The author's argument is poor because it is badly written.

Critical analysis

The author's argument is unconvincing without further supporting evidence.

Academic reading: What it is and how to do it

Struggling with academic reading? This bitesize workshop breaks it down for you! Discover how to read faster, smarter, and make those academic texts work for you:

Think critically about what you read...

- examine the evidence or arguments presented

- check out any influences on the evidence or arguments

- check out the limitations of study design or focus

- examine the interpretations made

Active critical reading

It's important to take an analytical approach to reading the texts you encounter. In the concluding part of our " Being critical " theme, we look at how to evaluate sources effectively, and how to develop practical strategies for reading in an efficient and critical manner.

Forthcoming training sessions

Forthcoming sessions on :

CITY College

Please ensure you sign up at least one working day before the start of the session to be sure of receiving joining instructions.

If you're based at CITY College you can book onto the following sessions by sending an email with the session details to your Faculty Librarian:

There's more training events at:

- << Previous: Reading academic articles

- Next: Critical writing >>

- Last Updated: Nov 14, 2024 4:37 PM

- URL: https://subjectguides.york.ac.uk/critical

COMMENTS

Critical analysis essentially involves reading and thinking widely about an issue in order to develop a deeper understanding of the topic. It is the detailed examination and evaluation of another persons ideas or work.

While critical analysis requires you to examine ideas, evaluate them against what you already know and make decisions about their merit, critical reflection requires you to synthesise different perspectives (whether from other people or literature) to help explain, justify or challenge what you have encountered in your own or other people’s ...

To read critically, you must think critically. This involves analysis, interpretation, and evaluation. Each of these processes helps you to interact with the text in different ways: highlighting important points and examples, taking notes, testing answers to your questions, brainstorming, outlining, describing aspects of the

Nov 26, 2024 · Critical Reading, also known as critical analysis, is the careful reading of a text by asking yourself functional questions to understand and assess the text's merits comprehensively. Analysing texts and finding answers to these questions enables you to gain clarity of what you're reading.

Jan 9, 2024 · Beyond basic comprehension, critical thinking empowers readers to synthesize, evaluate, and draw meaningful conclusions from scholarly texts. Through careful analysis, readers uncover...

Sep 1, 2024 · The model helps with critical reading through building fundamental reading skills (guessing the topic from the title and subtitles then deeper understanding of the content by making inferences, analysis, and synthesis) and then critical thinking about different details of the text.

This study aimed to investigate the effect of critical reading (CR) practices in science courses on academic achievement, science performance level, and problem-solving skills. The experimental method and factorial design were used.

As an effective critical reader you must be able to identify the important elements of a text and their function. To analyze means to break a text down into its parts to better understand it. When analyzing you notice both what the author is saying and how they are saying it.

Nov 14, 2024 · Critical reading is about engaging with the text by asking questions rather than passively accepting what it says. Is the methodology sound? What was the purpose? Do ideas flow logically? Are arguments properly formulated?

Jul 14, 2020 · Critical reading generally refers to reading in a scholarly context, with an eye toward identifying a text or author’s viewpoints, arguments, evidence, potential biases, and conclusions. Critical reading means evaluating what you have read using your knowledge as a scholar.