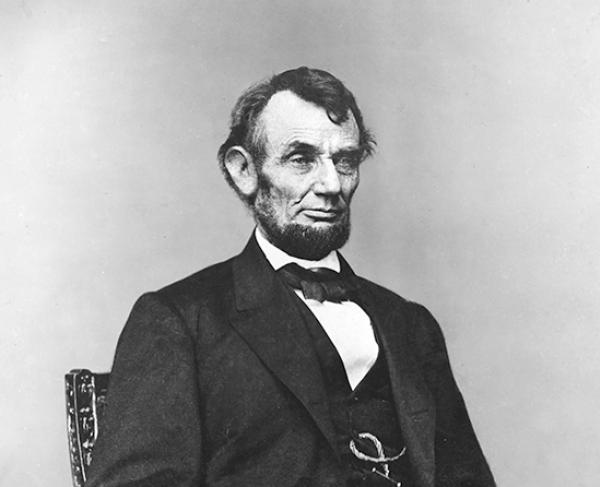

Abraham Lincoln

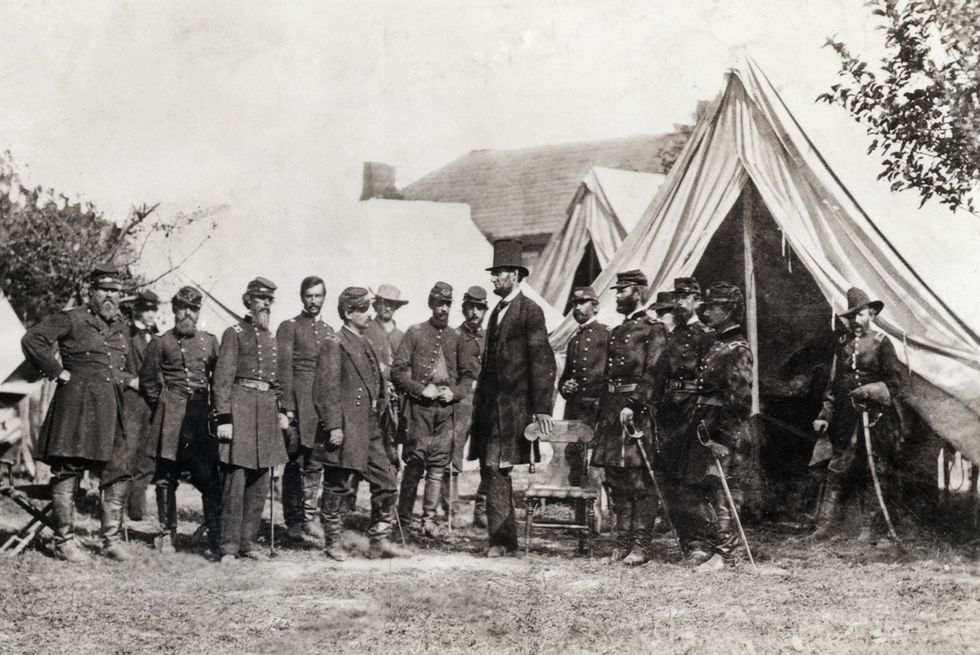

President Abraham Lincoln preserved the Union during the American Civil War and issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing enslaved people.

Who Was Abraham Lincoln?

Quick facts, early life, parents, and education, how tall was abraham lincoln, wrestling hobby and legal career, wife and children, political career, lincoln and slavery, senate race, u.s. president, civil war begins, emancipation proclamation, gettysburg address, civil war ends and lincoln’s reelection, assassination and funeral, abraham lincoln’s hat, abraham lincoln in movies and tv.

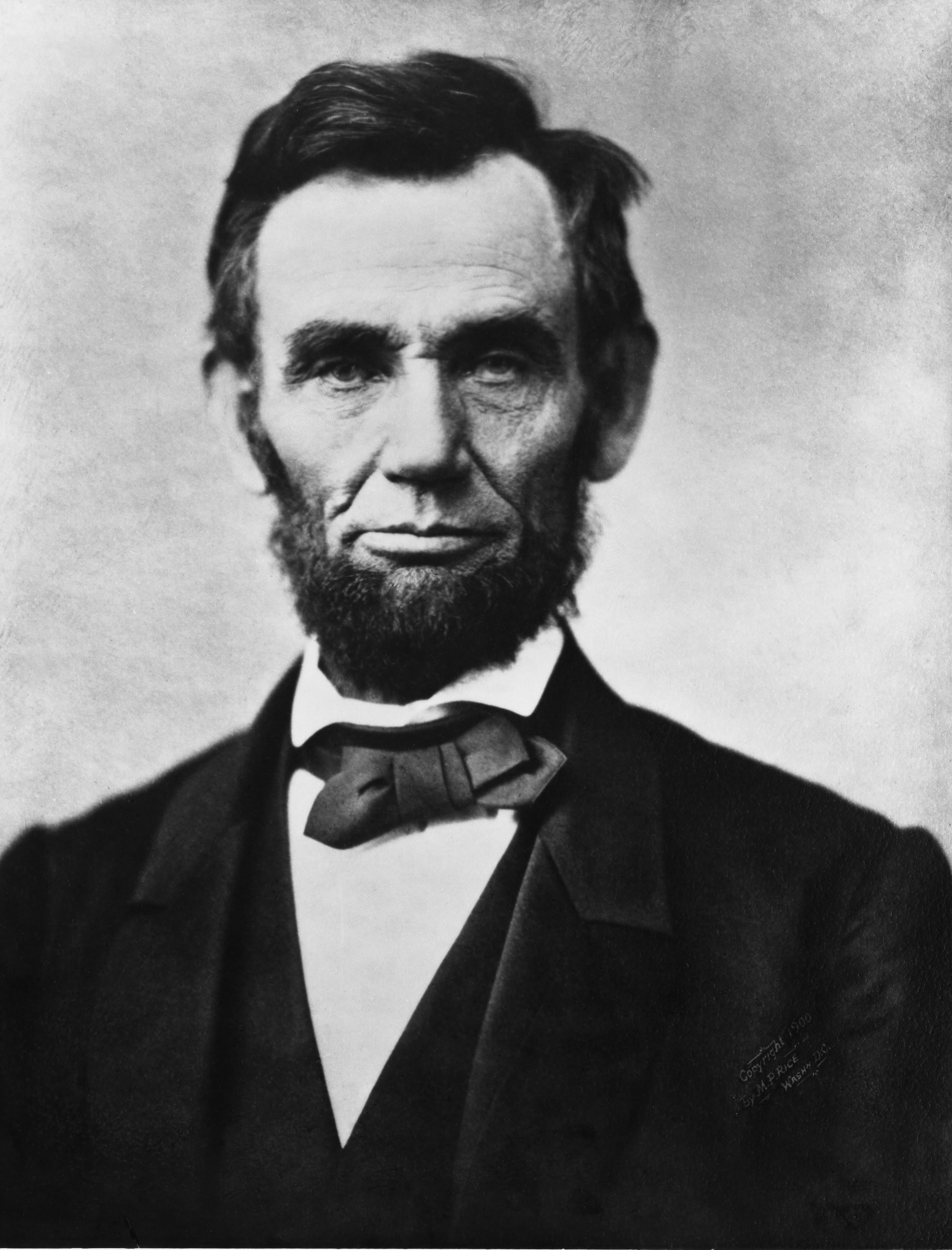

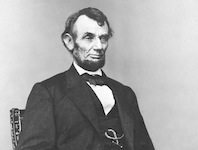

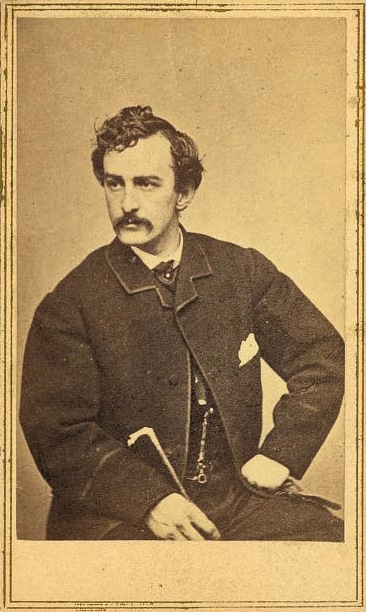

Abraham Lincoln was the 16 th president of the United States , serving from 1861 to 1865, and is regarded as one of America’s greatest heroes due to his roles in guiding the Union through the Civil War and working to emancipate enslaved people. His eloquent support of democracy and insistence that the Union was worth saving embody the ideals of self-government that all nations strive to achieve. In 1863, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed slaves across the Confederacy. Lincoln’s rise from humble beginnings to achieving the highest office in the land is a remarkable story, and his death is equally notably. He was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth in 1865, at age 56, as the country was slowly beginning to reunify following the war. Lincoln’s distinctively humane personality and incredible impact on the nation have endowed him with an enduring legacy.

FULL NAME: Abraham Lincoln BORN: February 12, 1809 DIED: April 15, 1865 BIRTHPLACE: Hodgenville, Kentucky SPOUSE: Mary Todd Lincoln (m. 1842) CHILDREN: Robert Todd Lincoln , Edward Baker Lincoln, William Wallace Lincoln, and Thomas “Tad” Lincoln ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Aquarius HEIGHT: 6 feet 4 inches

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, to parents Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks Lincoln in rural Hodgenville, Kentucky.

Thomas was a strong and determined pioneer who found a moderate level of prosperity and was well respected in the community. The couple had two other children: Lincoln’s older sister, Sarah, and younger brother, Thomas, who died in infancy. His death wasn’t the only tragedy the family would endure.

In 1817, the Lincolns were forced to move from young Abraham’s Kentucky birthplace to Perry County, Indiana, due to a land dispute. In Indiana, the family “squatted” on public land to scrap out a living in a crude shelter, hunting game and farming a small plot. Lincoln’s father was eventually able to buy the land.

When Lincoln was 9 years old, his 34-year-old mother died of tremetol, more commonly known as milk sickness, on October 5, 1818. The event was devastating to the young boy, who grew more alienated from his father and quietly resented the hard work placed on him at an early age.

In December 1819, just over a year after his mother’s death, Lincoln’s father Thomas married Sarah Bush Johnston, a Kentucky widow with three children of her own. She was a strong and affectionate woman with whom Lincoln quickly bonded.

Although both his parents were most likely illiterate, Thomas’ new wife Sarah encouraged Lincoln to read. It was while growing into manhood that Lincoln received his formal education—an estimated total of 18 months—a few days or weeks at a time.

Reading material was in short supply in the Indiana wilderness. Neighbors recalled how Lincoln would walk for miles to borrow a book. He undoubtedly read the family Bible and probably other popular books at that time such as Robinson Crusoe, Pilgrim’s Progres s, and Aesop’s Fable s.

In March 1830, the family again migrated, this time to Macon County, Illinois. When his father moved the family again to Coles County, 22-year-old Lincoln struck out on his own, making a living in manual labor.

Lincoln was 6 feet 4 inches tall, rawboned and lanky yet muscular and physically strong. He spoke with a backwoods twang and walked with a long-striding gait. He was known for his skill in wielding an ax and early on made a living splitting wood for fire and rail fencing.

Young Lincoln eventually migrated to the small community of New Salem, Illinois, where over a period of years he worked as a shopkeeper, postmaster, and eventually general store owner. It was through working with the public that Lincoln acquired social skills and honed a storytelling talent that made him popular with the locals.

Not surprising given his imposing frame, Lincoln was an excellent wrestler and had only one recorded loss—to Hank Thompson in 1832—over a span of 12 years. A shopkeeper who employed Lincoln in New Salem, Illinois, reportedly arranged bouts for him as a way to promote the business. Lincoln notably beat a local champion named Jack Armstrong and became somewhat of a hero. (The National Wrestling Hall of Fame posthumously gave Lincoln its Outstanding American Award in 1992.)

When the Black Hawk War broke out in 1832 between the United States and Native Americans, the volunteers in the area elected Lincoln to be their captain. He saw no combat during this time, save for “a good many bloody struggles with the mosquitoes,” but was able to make several important political connections.

As he was starting his political career in the early 1830s, Lincoln decided to become a lawyer. He taught himself the law by reading William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England . After being admitted to the bar in 1837, he moved to Springfield, Illinois, and began to practice in the John T. Stuart law firm.

In 1844, Lincoln partnered with William Herndon in the practice of law. Although the two had different jurisprudent styles, they developed a close professional and personal relationship.

Lincoln made a good living in his early years as a lawyer but found that Springfield alone didn’t offer enough work. So to supplement his income, he followed the court as it made its rounds on the circuit to the various county seats in Illinois.

On November 4, 1842, Lincoln wed Mary Todd , a high-spirited, well-educated woman from a distinguished Kentucky family. Although they were married until Lincoln’s death, their relationship had a history of instability.

When the couple became engaged in 1840, many of their friends and family couldn’t understand Mary’s attraction; at times, Lincoln questioned it himself. In 1841, the engagement was suddenly broken off, most likely at Lincoln’s initiative. Mary and Lincoln met later at a social function and eventually did get married.

The couple had four sons— Robert Todd , Edward Baker, William Wallace, and Thomas “Tad”—of whom only Robert survived to adulthood.

Before marrying Todd, Lincoln was involved with other potential matches. Around 1837, he purportedly met and became romantically involved with Anne Rutledge. Before they had a chance to be engaged, a wave of typhoid fever came over New Salem, and Anne died at age 22.

Her death was said to have left Lincoln severely depressed. However, several historians disagree on the extent of Lincoln’s relationship with Rutledge, and his level of sorrow at her death might be more the makings of legend.

About a year after the death of Rutledge, Lincoln courted Mary Owens. The two saw each other for a few months, and marriage was considered. But in time, Lincoln called off the match.

In 1834, Lincoln began his political career and was elected to the Illinois state legislature as a member of the Whig Party . More than a decade later, from 1847 to 1849, he served a single term in the U.S. House of Representatives. His foray into national politics seemed to be as unremarkable as it was brief. He was the lone Whig from Illinois, showing party loyalty but finding few political allies.

As a congressman, Lincoln used his term in office to speak out against the Mexican-American War and supported Zachary Taylor for president in 1848. His criticism of the war made him unpopular back home, and he decided not to run for second term. Instead, he returned to Springfield to practice law.

By the 1850s, the railroad industry was moving west, and Illinois found itself becoming a major hub for various companies. Lincoln served as a lobbyist for the Illinois Central Railroad as its company attorney.

Success in several court cases brought other business clients as well, including banks, insurance companies, and manufacturing firms. Lincoln also worked in some criminal trials.

In one case, a witness claimed that he could identify Lincoln’s client who was accused of murder, because of the intense light from a full moon. Lincoln referred to an almanac and proved that the night in question had been too dark for the witness to see anything clearly. His client was acquitted.

As a member of the Illinois state legislature, Lincoln supported the Whig politics of government-sponsored infrastructure and protective tariffs. This political understanding led him to formulate his early views on slavery, not so much as a moral wrong, but as an impediment to economic development.

In 1854, Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act , which repealed the Missouri Compromise , allowing individual states and territories to decide for themselves whether to allow slavery. The law provoked violent opposition in Kansas and Illinois, and it gave rise to today’s Republican Party .

This awakened Lincoln’s political zeal once again, and his views on slavery moved more toward moral indignation. Lincoln joined the Republican Party in 1856.

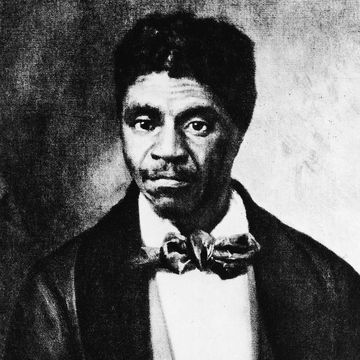

In 1857, the Supreme Court issued its controversial Dred Scott decision, declaring Black people were not citizens and had no inherent rights. Although Lincoln felt Black people weren’t equal to whites, he believed America’s founders intended that all men were created with certain inalienable rights.

Lincoln decided to challenge sitting U.S. Senator Stephen Douglas for his seat. In his nomination acceptance speech, he criticized Douglas, the Supreme Court , and President James Buchanan for promoting slavery then declared “a house divided cannot stand.”

During Lincoln’s 1858 U.S. Senate campaign against Douglas, he participated in seven debates held in different cities across Illinois. The two candidates didn’t disappoint, giving stirring debates on issues such as states’ rights and western expansion. But the central issue was slavery.

Newspapers intensely covered the debates, often times with partisan commentary. In the end, the state legislature elected Douglas, but the exposure vaulted Lincoln into national politics.

With his newly enhanced political profile, in 1860, political operatives in Illinois organized a campaign to support Lincoln for the presidency. On May 18, at the Republican National Convention in Chicago, Lincoln surpassed better-known candidates such as William Seward of New York and Salmon P. Chase of Ohio. Lincoln’s nomination was due, in part, to his moderate views on slavery, his support for improving the national infrastructure, and the protective tariff.

In the November 1860 general election, Lincoln faced his friend and rival Stephen Douglas, this time besting him in a four-way race that included John C. Breckinridge of the Northern Democrats and John Bell of the Constitution Party. Lincoln received not quite 40 percent of the popular vote but carried 180 of 303 Electoral College votes, thus winning the U.S. presidency. He grew his trademark beard after his election.

Lincoln’s Cabinet

Following his election to the presidency in 1860, Lincoln selected a strong cabinet composed of many of his political rivals, including William Seward, Salmon P. Chase, Edward Bates, and Edwin Stanton.

Formed out the adage “Hold your friends close and your enemies closer,” Lincoln’s cabinet became one of his strongest assets in his first term in office, and he would need them as the clouds of war gathered over the nation the following year.

Before Lincoln’s inauguration in March 1861, seven Southern states had seceded from the Union, and by April, the U.S. military installation Fort Sumter was under siege in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. In the early morning hours of April 12, 1861, the guns stationed to protect the harbor blazed toward the fort, signaling the start of the U.S. Civil War , America’s costliest and bloodiest war.

The newly President Lincoln responded to the crisis wielding powers as no other president before him: He distributed $2 million from the Treasury for war material without an appropriation from Congress; he called for 75,000 volunteers into military service without a declaration of war; and he suspended the writ of habeas corpus, allowing for the arrest and imprisonment of suspected Confederate States sympathizers without a warrant.

Crushing the rebellion would be difficult under any circumstances, but the Civil War, after decades of white-hot partisan politics, was especially onerous. From all directions, Lincoln faced disparagement and defiance. He was often at odds with his generals, his cabinet, his party, and a majority of the American people.

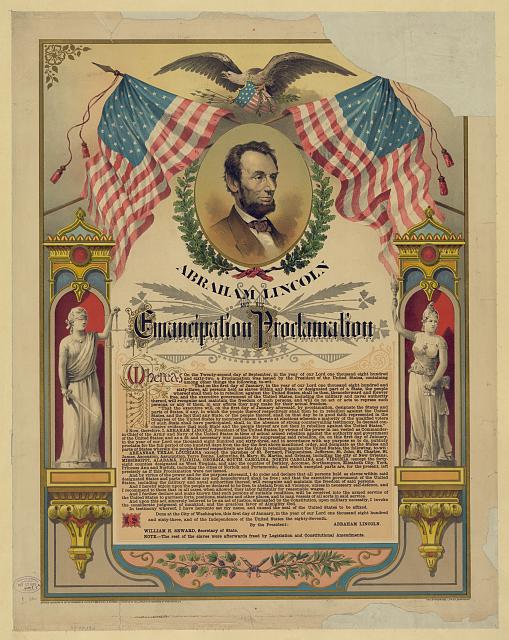

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln delivered his official Emancipation Proclamation , reshaping the cause of the Civil War from saving the Union to abolishing slavery.

The Union Army’s first year and a half of battlefield defeats made it difficult to keep morale high and support strong for a reunification of the nation. And the Union victory at Antietam on September 22, 1862, while by no means conclusive, was hopeful. It gave Lincoln the confidence to officially change the goals of the war. On that same day, he issued a preliminary proclamation that slaves in states rebelling against the Union would be free as of January 1.

The Emancipation Proclamation stated that all individuals who were held as enslaved people in rebellious states “henceforward shall be free.” The action was more symbolic than effective because the North didn’t control any states in rebellion, and the proclamation didn’t apply to border states, Tennessee, or some Louisiana parishes.

As a result, the Union army shared the Proclamation’s mandate only after it had taken control of Confederate territory. In the far reaches of western Texas, that day finally came on June 19, 1865—more than two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation took effect. For decades, many Black Americans have celebrated this anniversary, known as Juneteenth or Emancipation Day, and in 2021, President Joe Biden made Juneteenth a national holiday.

Still, the Emancipation Proclamation did have some immediate impact. It permitted Black Americans to serve in the Union Army for the first time, which contributed to the eventual Union victory. The historic declaration also paved the way for the passage of the 13 th Amendment that ended legal slavery in the United States.

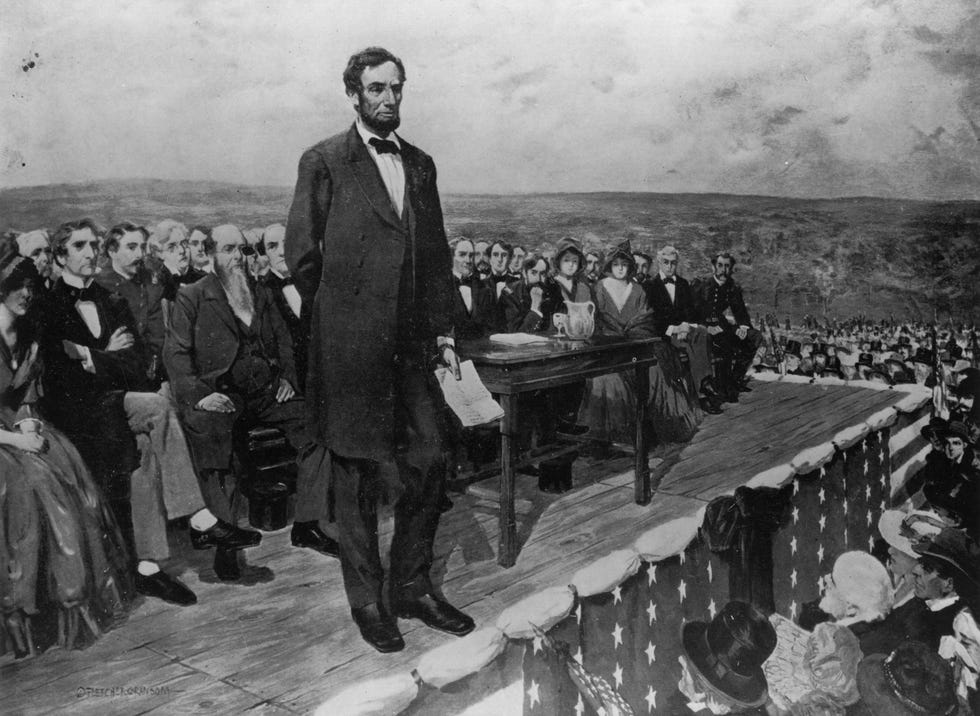

On November 19, 1863, Lincoln delivered what would become his most famous speech and one of the most important speeches in American history: the Gettysburg Address .

Addressing a crowd of around 15,000 people, Lincoln delivered his 272-word speech at one of the bloodiest battlefields of the Civil War, the Gettysburg National Cemetery in Pennsylvania. The Civil War, Lincoln said, was the ultimate test of the preservation of the Union created in 1776, and the people who died at Gettysburg fought to uphold this cause.

Lincoln evoked the Declaration of Independence , saying it was up to the living to ensure that the “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth,” and this Union was “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

A common interpretation was that the president was expanding the cause of the Civil War from simply reunifying the Union to also fighting for equality and abolishing slavery.

Following Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, the war effort gradually improved for the North, though more by attrition than by brilliant military victories.

But by 1864, the Confederate armies had eluded major defeat and Lincoln was convinced he’d be a one-term president. His nemesis George B. McClellan , the former commander of the Army of the Potomac, challenged him for the presidency, but the contest wasn’t even close. Lincoln received 55 percent of the popular vote and 212 of 243 electoral votes.

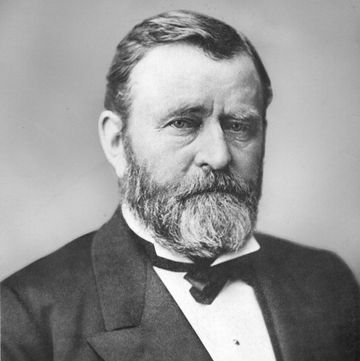

On April 9, 1865, General Robert E. Lee , commander of the Army of Virginia, surrendered his forces to Union General Ulysses S. Grant . The Civil War was for all intents and purposes over.

Reconstruction had already began during the Civil War, as early as 1863 in areas firmly under Union military control, and Lincoln favored a policy of quick reunification with a minimum of retribution. He was confronted by a radical group of Republicans in Congress that wanted complete allegiance and repentance from former Confederates. Before a political debate had any chance to firmly develop, Lincoln was killed.

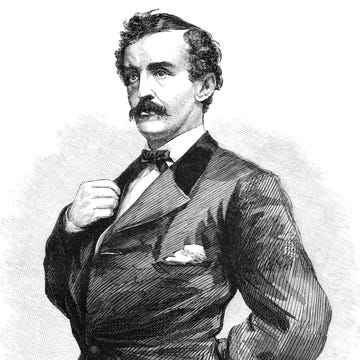

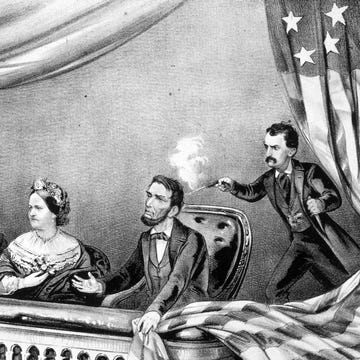

Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, 1865, by well-known actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theatre in Washington. Lincoln was taken to the Petersen House across the street and laid in a coma for nine hours before dying the next morning. He was 56. His death was mourned by millions of citizens in the North and South alike.

Lincoln’s body first lay in state at the U. S. Capitol. About 600 invited guests attended a funeral in the East Room of the White House on April 19, though an inconsolable Mary Todd Lincoln wasn’t present.

His body was transported to his final resting place in Springfield, Illinois, by a funeral train. Newspapers publicized the schedule of the train, which made stops along various cities that played roles in Lincoln’s path to Washington. In 10 cities, the casket was removed and placed in public for memorial services. Lincoln was finally placed in a tomb on May 4.

On the day of Lincoln’s death, Andrew Johnson was sworn in as the 17 th president at the Kirkwood House hotel in Washington.

Lincoln, already taller than most, is known for his distinctive top hats. Although it’s unclear when he began wearing them, historians believe he likely chose the style as a gimmick.

He wore a top hat to Ford’s Theatre on the night of his assassination. Following his death, the War Department preserved the hat until 1867 when, with Mary Todd Lincoln’s approval, it was transferred to the Patent Office and the Smithsonian Institution. Worried about the commotion it might cause, the Smithsonian stored the hat in a basement instead of putting it on display. It was finally exhibited in 1893, and it’s now one of the Institution’s most treasured items.

Lincoln is frequently cited by historians and average citizens alike as America’s greatest president. An aggressively activist commander-in-chief, Lincoln used every power at his disposal to assure victory in the Civil War and end slavery in the United States.

Some scholars doubt that the Union would have been preserved had another person of lesser character been in the White House. According to historian Michael Burlingame , “No president in American history ever faced a greater crisis and no president ever accomplished as much.”

Lincoln’s philosophy was perhaps best summed up in his Second Inaugural Address , when he stated, “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

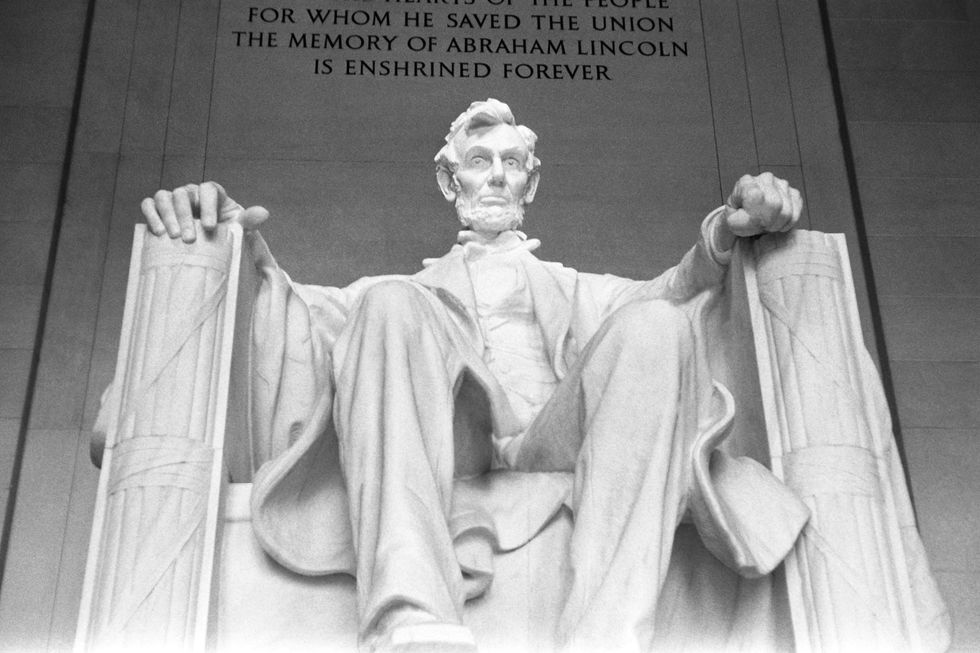

The Lincoln Memorial

Since its dedication in 1922, the Lincoln Memorial in Washington has honored the president’s legacy. Inspired by the Greek Parthenon, the monument features a 19-foot high statue of Lincoln and engravings of the Gettysburg Address and Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address. Former President William Howard Taft served as chair of the Lincoln Memorial Commission, which oversaw its design and construction.

The monument is the most visited in the city, attracting around 8 million people per year. Civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech on the memorial’s steps in 1963.

Lincoln has been the subject of numerous films about his life and presidency, rooted in both realism and absurdity.

Among the earlier films featuring the former president is Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), which stars Henry Fonda and focuses on Lincoln’s early life and law career. A year later, Abe Lincoln in Illinois gave a dramatized account of Lincoln’s life after leaving Kentucky.

The most notable modern film is Lincoln , the 2012 biographical drama directed by Steven Spielberg and starring Daniel Day-Lewis as Lincoln and Sally Field as his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln . Day-Lewis won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance, and the film was nominated for Best Picture.

A more fantastical depiction of Lincoln came in the 1989 comedy film Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure , in which the titular characters played by Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter travel back in time for the president’s help in completing their high school history report. Lincoln gives the memorable instruction to “be excellent to each other and... party on, dudes!”

Another example is the 2012 action film Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter , based on a 2010 novel by Seth Grahame-Smith. Benjamin Walker plays Lincoln, who leads a secret double life hunting the immortal creatures and even fighting them during the Civil War.

Lincoln’s role during the Civil War is heavily explored in the 1990 Ken Burns documentary The Civil War , which won two Emmy Awards and two Grammys. In 2022, the History Channel aired a three-part docuseries about his life simply titled Abraham Lincoln .

- Those who deny freedom to others deserve it not for themselves.

- I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me.

- No man is good enough to govern another man, without that other ’ s consent.

- I have learned the value of old friends by making many new ones.

- Government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

- Whenever I hear anyone arguing over slavery, I feel a strong impulse to see it tried on him personally.

- To give the victory to the right, not bloody bullets, but peaceful ballots only, are necessary.

- Our defense is in the preservation of the spirit which prizes liberty as the heritage of all men, in all lands, everywhere. Destroy this spirit, and you have planted the seeds of despotism around your own doors.

- Don ’ t interfere with anything in the Constitution. That must be maintained, for it is the only safeguard of our liberties.

- Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed is more important than any other one thing.

- With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation ’ s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

- I walk slowly, but I never walk backward.

- Nearly all men can handle adversity, if you want to test a man’s character, give him power.

- I ’ m the big buck of this lick. If any of you want to try it, come on and whet your horns.

- We can complain because rose bushes have thorns.

- Am I not destroying my enemies when I make friends of them?

- It is better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to open one’s mouth and remove all doubt.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Tyler Piccotti joined the Biography.com staff as an Associate News Editor and is now the News and Culture Editor. He previously worked as a reporter and copy editor for a daily newspaper recognized by the Associated Press Sports Editors. In his current role, he shares the true stories behind your favorite movies and TV shows and profiles rising musicians, actors, and athletes. When he's not working, you can find him at the nearest amusement park or movie theater and cheering on his favorite teams.

Civil War Figures

The Manhunt for John Wilkes Booth

The 13 Most Cunning Military Leaders

Clara Barton

The Story of President Ulysses S. Grant’s Arrest

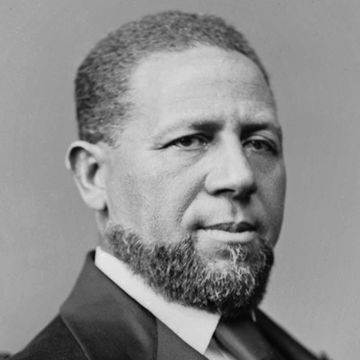

Hiram R. Revels

John Wilkes Booth

The Final Days of Abraham Lincoln

Stonewall Jackson

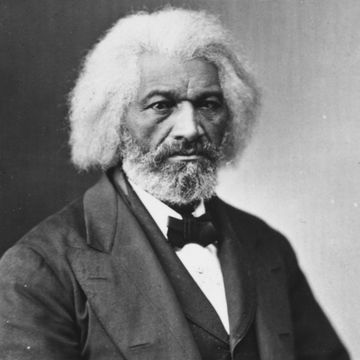

Frederick Douglass

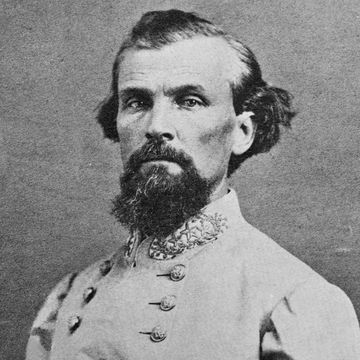

Nathan Bedford Forrest

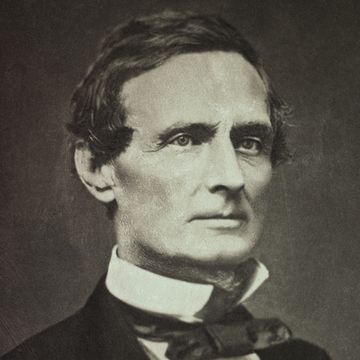

Jefferson Davis

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Abraham Lincoln

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 7, 2024 | Original: October 29, 2009

Abraham Lincoln , a self-taught lawyer, legislator and vocal opponent of slavery, was elected 16th president of the United States in November 1860, shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War. Lincoln proved to be a shrewd military strategist and a savvy leader: His Emancipation Proclamation paved the way for slavery’s abolition, while his Gettysburg Address stands as one of the most famous pieces of oratory in American history.

In April 1865, with the Union on the brink of victory, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth. Lincoln’s assassination made him a martyr to the cause of liberty, and he is widely regarded as one of the greatest presidents in U.S. history.

Abraham Lincoln's Childhood and Early Life

Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, to Nancy and Thomas Lincoln in a one-room log cabin in Hardin County, Kentucky . His family moved to southern Indiana in 1816. Lincoln’s formal schooling was limited to three brief periods in local schools, as he had to work constantly to support his family.

In 1830, his family moved to Macon County in southern Illinois , and Lincoln got a job working on a river flatboat hauling freight down the Mississippi River to New Orleans . After settling in the town of New Salem, Illinois, where he worked as a shopkeeper and a postmaster, Lincoln became involved in local politics as a supporter of the Whig Party , winning election to the Illinois state legislature in 1834.

Like his Whig heroes Henry Clay and Daniel Webster , Lincoln opposed the spread of slavery to the territories, and had a grand vision of the expanding United States, with a focus on commerce and cities rather than agriculture.

Did you know? The war years were difficult for Abraham Lincoln and his family. After his young son Willie died of typhoid fever in 1862, the emotionally fragile Mary Lincoln, widely unpopular for her frivolity and spendthrift ways, held seances in the White House in the hopes of communicating with him, earning her even more derision.

Lincoln taught himself law, passing the bar examination in 1836. The following year, he moved to the newly named state capital of Springfield. For the next few years, he worked there as a lawyer and served clients ranging from individual residents of small towns to national railroad lines.

He met Mary Todd , a well-to-do Kentucky belle with many suitors (including Lincoln’s future political rival, Stephen Douglas ), and they married in 1842. The Lincolns went on to have four children together, though only one would live into adulthood: Robert Todd Lincoln (1843–1926), Edward Baker Lincoln (1846–1850), William Wallace Lincoln (1850–1862) and Thomas “Tad” Lincoln (1853-1871).

Abraham Lincoln Enters Politics

Lincoln won election to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1846 and began serving his term the following year. As a congressman, Lincoln was unpopular with many Illinois voters for his strong stance against the Mexican-American War. Promising not to seek reelection, he returned to Springfield in 1849.

Events conspired to push him back into national politics, however: Douglas, a leading Democrat in Congress, had pushed through the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854), which declared that the voters of each territory, rather than the federal government, had the right to decide whether the territory should be slave or free.

On October 16, 1854, Lincoln went before a large crowd in Peoria to debate the merits of the Kansas-Nebraska Act with Douglas, denouncing slavery and its extension and calling the institution a violation of the most basic tenets of the Declaration of Independence .

With the Whig Party in ruins, Lincoln joined the new Republican Party–formed largely in opposition to slavery’s extension into the territories–in 1856 and ran for the Senate again that year (he had campaigned unsuccessfully for the seat in 1855 as well). In June, Lincoln delivered his now-famous “house divided” speech, in which he quoted from the Gospels to illustrate his belief that “this government cannot endure, permanently, half slave and half free.”

Lincoln then squared off against Douglas in a series of famous debates; though he lost the Senate election, Lincoln’s performance made his reputation nationally.

Abraham Lincoln’s Frontier Childhood Was Filled With Hardship

Rugged conditions. Heavy labor. Minimal schooling. And a mother gone too soon.

How a Female Pinkerton Detective Helped Save Abraham Lincoln’s Life

In 1861, Kate Warne kept the president‑elect safe from an assassination plot on his train journey to Washington.

5 Things You May Not Know About Abraham Lincoln, Slavery and Emancipation

The 16th U.S. president was firm in believing slavery was morally wrong, but his views on racial equality were sometimes more complicated.

Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 Presidential Campaign

Lincoln’s profile rose even higher in early 1860 after he delivered another rousing speech at New York City’s Cooper Union. That May, Republicans chose Lincoln as their candidate for president, passing over Senator William H. Seward of New York and other powerful contenders in favor of the rangy Illinois lawyer with only one undistinguished congressional term under his belt.

In the general election, Lincoln again faced Douglas, who represented the northern Democrats; southern Democrats had nominated John C. Breckenridge of Kentucky, while John Bell ran for the brand new Constitutional Union Party. With Breckenridge and Bell splitting the vote in the South, Lincoln won most of the North and carried the Electoral College to win the White House .

He built an exceptionally strong cabinet composed of many of his political rivals, including Seward, Salmon P. Chase, Edward Bates and Edwin M. Stanton .

Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War

After years of sectional tensions, the election of an antislavery northerner as the 16th president of the United States drove many southerners over the brink. By the time Lincoln was inaugurated as 16th U.S. president in March 1861, seven southern states had seceded from the Union and formed the Confederate States of America .

Lincoln ordered a fleet of Union ships to supply the federal Fort Sumter in South Carolina in April. The Confederates fired on both the fort and the Union fleet, beginning the Civil War . Hopes for a quick Union victory were dashed by defeat in the Battle of Bull Run (Manassas) , and Lincoln called for 500,000 more troops as both sides prepared for a long conflict.

While the Confederate leader Jefferson Davis was a West Point graduate, Mexican War hero and former secretary of war, Lincoln had only a brief and undistinguished period of service in the Black Hawk War (1832) to his credit. He surprised many when he proved to be a capable wartime leader, learning quickly about strategy and tactics in the early years of the Civil War, and about choosing the ablest commanders.

General George McClellan , though beloved by his troops, continually frustrated Lincoln with his reluctance to advance, and when McClellan failed to pursue Robert E. Lee’s retreating Confederate Army in the aftermath of the Union victory at Antietam in September 1862, Lincoln removed him from command.

During the war, Lincoln drew criticism for suspending some civil liberties, including the right of habeas corpus , but he considered such measures necessary to win the war.

Emancipation Proclamation and Gettysburg Address

Shortly after the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg), Lincoln issued a preliminary Emancipation Proclamation , which took effect on January 1, 1863, and freed all of the enslaved people in the rebellious states not under federal control, but left those in the border states (loyal to the Union) in bondage.

Though Lincoln once maintained that his “paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy slavery,” he nonetheless came to regard emancipation as one of his greatest achievements and would argue for the passage of a constitutional amendment outlawing slavery (eventually passed as the 13th Amendment after his death in 1865).

Two important Union victories in July 1863—at Vicksburg, Mississippi, and at the Battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania—finally turned the tide of the war. General George Meade missed the opportunity to deliver a final blow against Lee’s army at Gettysburg, and Lincoln would turn by early 1864 to the victor at Vicksburg, Ulysses S. Grant , as supreme commander of the Union forces.

In November 1863, Lincoln delivered a brief speech (just 272 words) at the dedication ceremony for the new national cemetery at Gettysburg. Published widely, the Gettysburg Address eloquently expressed the war’s purpose, harking back to the Founding Fathers, the Declaration of Independence and the pursuit of human equality. It became the most famous speech of Lincoln’s presidency, and one of the most widely quoted speeches in history.

Abraham Lincoln Wins 1864 Presidential Election

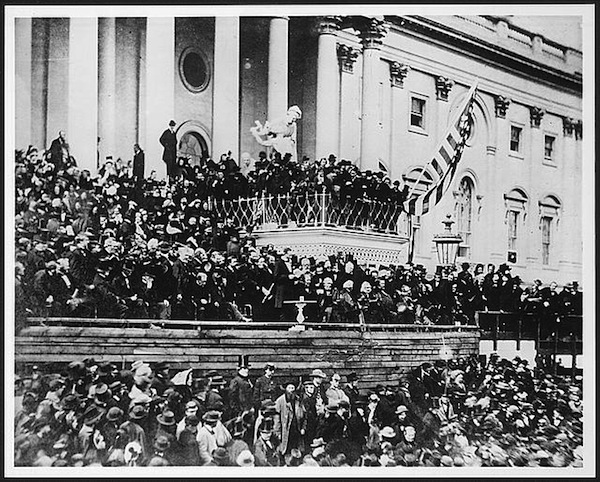

In 1864, Lincoln faced a tough reelection battle against the Democratic nominee, the former Union General George McClellan, but Union victories in battle (especially General William T. Sherman’s capture of Atlanta in September) swung many votes the president’s way. In his second inaugural address, delivered on March 4, 1865, Lincoln addressed the need to reconstruct the South and rebuild the Union: “With malice toward none; with charity for all.”

As Sherman marched triumphantly northward through the Carolinas after staging his March to the Sea from Atlanta, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House , Virginia , on April 9. Union victory was near, and Lincoln gave a speech on the White House lawn on April 11, urging his audience to welcome the southern states back into the fold. Tragically, Lincoln would not live to help carry out his vision of Reconstruction .

How Lincoln and Grant’s Partnership Won the Civil War

Abraham Lincoln was disappointed by most of his generals—but not Ulysses S. Grant.

Abraham Lincoln in Photos: How the Presidency Aged Him

Photographs taken of Lincoln between 1859 and 1865 reveal how increasingly careworn he became.

Abraham Lincoln’s Funeral Train: How America Mourned for Three Weeks

Millions of Americans bade farewell to the assassinated president as his body made a 1,700‑mile journey home.

Abraham Lincoln’s Assassination

On the night of April 14, 1865, the actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth slipped into the president’s box at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., and shot him point-blank in the back of the head. Lincoln was carried to a boardinghouse across the street from the theater, but he never regained consciousness, and died in the early morning hours of April 15, 1865.

Lincoln’s assassination made him a national martyr. On April 21, 1865, a train carrying his coffin left Washington, D.C. on its way to Springfield, Illinois, where he would be buried on May 4. Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train traveled through 180 cities and seven states so mourners could pay homage to the fallen president.

Today, Lincoln’s birthday—alongside the birthday of George Washington —is honored on President’s Day , which falls on the third Monday of February.

Abraham Lincoln Quotes

“Nothing valuable can be lost by taking time.”

“I want it said of me by those who knew me best, that I always plucked a thistle and planted a flower where I thought a flower would grow.”

“I am rather inclined to silence, and whether that be wise or not, it is at least more unusual nowadays to find a man who can hold his tongue than to find one who cannot.”

“I am exceedingly anxious that this Union, the Constitution, and the liberties of the people shall be perpetuated in accordance with the original idea for which that struggle was made, and I shall be most happy indeed if I shall be a humble instrument in the hands of the Almighty, and of this, his almost chosen people, for perpetuating the object of that great struggle.”

“This is essentially a People's contest. On the side of the Union, it is a struggle for maintaining in the world, that form, and substance of government, whose leading object is, to elevate the condition of men—to lift artificial weights from all shoulders—to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all—to afford all, an unfettered start, and a fair chance, in the race of life.”

“Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

“This nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

HISTORY Vault: Abraham Lincoln

A definitive biography of the 16th U.S. president, the man who led the country during its bloodiest war and greatest crisis.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln, sixteenth President of the United States, was born near Hodgenville, Kentucky on February 12, 1809. His family moved to Indiana when he was seven and he grew up on the edge of the frontier. He had very little formal education, but read voraciously when not working on his father’s farm. A childhood friend later recalled Lincoln's "manic" intellect, and the sight of him red-eyed and tousle-haired as he pored over books late into the night. In 1828, at the age of nineteen, he accompanied a produce-laden flatboat down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, Louisiana—his first visit to a large city--and then walked back home. Two years later, trying to avoid health and finance troubles, Lincoln's father moved the family moved to Illinois.

After moving away from home, Lincoln co-owned a general store for several years before selling his stake and enlisting as a militia captain defending Illinois in the Black Hawk War of 1832. Black Hawk, a Sauk chief, believed he had been swindled by a recent land deal and sought to resettle his old holdings. Lincoln did not see direct combat during the short conflict, but the sight of corpse-strewn battlefields at Stillman's Run and Kellogg's Grove deeply affected him. As a captain, he developed a reputation for pragmatism and integrity. Once, faced with a rail fence during practice maneuvers and forgetting the parade-ground instructions to direct his men over it, he simply ordered them to fall out and reassemble on the other side a minute later. Another time, he stopped his men before they executed a wandering Native American as a spy. Stepping in front of their raised muskets, Lincoln is said to have challenged his men to combat for the terrified native's life. His men stood down.

After the war, he studied law and campaigned for a seat on the Illinois State Legislature. Although not elected in his first attempt, Lincoln persevered and won the position in 1834, serving as a Whig.

Abraham Lincoln met Mary Todd in Springfield, Illinois where he was practicing as a lawyer. They were married in 1842 over her family’s objections and had four sons. Only one lived to adulthood. The deep melancholy that pervaded the Lincoln family, with occasional detours into outright madness, is in some ways sourced in their close relationship with death.

Lincoln, a self-described "prairie lawyer," focused on his all-embracing law practice in the early 1850s after one term in Congress from 1847 to 1849. He joined the new Republican party—and the ongoing argument over sectionalism—in 1856. A series of heated debates in 1858 with Stephen A. Douglas , the sponsor of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act , over slavery and its place in the United States forged Lincoln into a prominent figure in national politics. Lincoln’s anti-slavery platform made him extremely unpopular with Southerners and his nomination for President in 1860 enraged them.

On November 6, 1860, Lincoln won the presidential election without the support of a single Southern state. Talk of secession, bandied about since the 1830s, took on a serious new tone. The Civil War was not entirely caused by Lincoln’s election, but the election was one of the primary reasons the war broke out the following year.

Lincoln’s decision to fight rather than to let the Southern states secede was not based on his feelings towards slavery. Rather, he felt it was his sacred duty as President of the United States to preserve the Union at all costs. His first inaugural address was an appeal to the rebellious states, seven of which had already seceded, to rejoin the nation. His first draft of the speech ended with an ominous message: "Shall it be peace, or the sword?"

The Civil War began with the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter , South Carolina, on April 12, 1861. Fort Sumter, situated in the Charleston Harbour, was a Union outpost in the newly seceded Confederate territory. Lincoln, learning that the Fort was running low on food, sent supplies to reinforce the soldiers there. The Southern navy repulsed the supply convoy. After this repulse, the Southern navy fired the first shot of the war at Fort Sumter and the Federal defenders surrendered after a 34-hour long battle.

Throughout the war, Lincoln struggled to find capable generals for his armies. As commander-in-chief, he legally held the highest rank in the United States armed forces, and he diligently exercised his authority through strategic planning, weapons testing, and the promotion and demotion of officers. McDowell , Fremont, McClellan , Pope , McClellan again, Buell , Burnside , Rosecrans --all of these men and more withered under Lincoln's watchful eye as they failed to bring him success on the battlefield.

He did not issue his famous Emancipation Proclamation until January 1, 1863 after the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam . The Emancipation Proclamation, which was legally based on the President’s right to seize the property of those in rebellion against the State, only freed slaves in Southern states where Lincoln’s forces had no control. Nevertheless, it changed the tenor of the war, making it, from the Northern point of view, a fight both to preserve the Union and to end slavery.

In 1864, Lincoln ran again for President. After years of war, he feared he would not win. Only in the final months of the campaign did the exertions of Ulysses S. Grant , the quiet general now in command of all of the Union armies, begin to bear fruit. A string of heartening victories buoyed Lincoln's ticket and contributed significantly to his re-election. In his second inauguration speech , March 4, 1865, he set the tone he intended to take when the war finally ended. His one goal, he said, was “lasting peace among ourselves.” He called for “malice towards none” and “charity for all.” The war ended only a month later.

The Lincoln administration did more than just manage the Civil War, although its reverberations could still be felt in a number of policies. The Revenue Act of 1862 established the United States' first income tax, largely to pay the costs of total war. The Morrill Act of 1862 established the basis of the state university system in this country, while the Homestead Act, also passed in 1862, encouraged settlement of the West by offering 160 acres of free land to settlers. Lincoln also created the Department of Agriculture and formally instituted the Thanksgiving holiday. Internationally, he navigated the "Trent Affair," a diplomatic crisis regarding the seizure of a British ship carrying Confederate envoys, in such a way as to quell the saber-rattling overtures coming from Britain as well as the United States. In another spill-over from the war, Lincoln restricted the civil liberties of due process and freedom of the press.

On April 14, 1865, while attending a play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., Abraham Lincoln was shot by Confederate sympathizer, John Wilkes Booth. The assassination was part of a larger plot to eliminate the Northern government that also left Secretary of State William Seward grievously injured. Lincoln died the following day, and with him the hope of reconstructing the nation without bitterness.

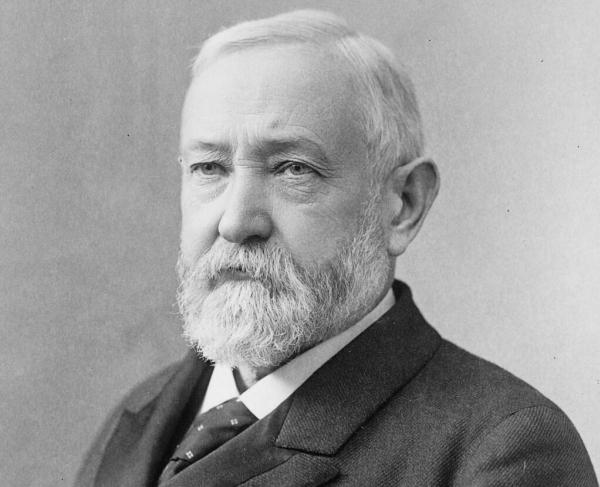

Benjamin Harrison

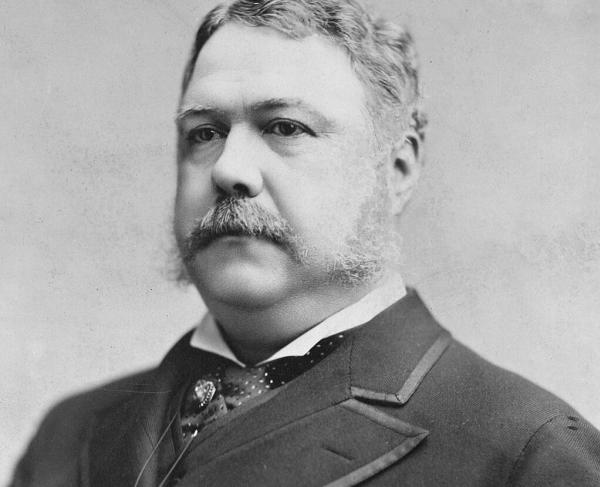

Chester A. Arthur

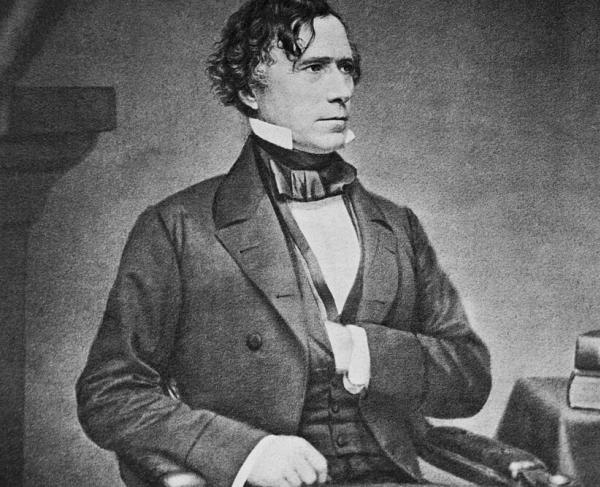

Franklin Pierce

You may also like.

Help inform the discussion

- X (Twitter)

Abraham Lincoln: Life in Brief

When Abraham Lincoln was elected President in 1860, seven slave states left the Union to form the Confederate States of America, and four more joined when hostilities began between the North and South. A bloody civil war then engulfed the nation as Lincoln vowed to preserve the Union, enforce the laws of the United States, and end the secession. The war lasted for more than four years with a staggering loss of more than 600,000 Americans dead. Midway through the war, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed all slaves within the Confederacy and changed the war from a battle to preserve the Union into a battle for freedom. He was the first Republican President, and Union victory ended forever the claim that state sovereignty superseded federal authority. Killed by an assassin's bullet less than a week after the surrender of Confederate forces, Lincoln left the nation a more perfect Union and thereby earned the admiration of most Americans as the country's greatest President.

Born dirt-poor in a log cabin in Kentucky in 1809, Lincoln grew up in frontier Kentucky and Indiana, where he was largely self-educated, with a taste for jokes, hard work, and books. He served for a time as a soldier in the Black Hawk War, taught himself law, and held a seat in the Illinois state legislature as a Whig politician in the 1830s and 1840s. From state politics, he moved to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1847, where he voiced his opposition to the U.S. war with Mexico. In the mid-1850s, Lincoln left the Whig Party to join the new Republican Party. In 1858, he went up against one of the most popular politicians in the nation, Senator Stephen Douglas, in a contest for the U.S. Senate. Lincoln lost that election, but his spectacular performance against Douglas in a series of nationally covered debates made him a contender for the 1860 Republican presidential nomination.

Fighting for Unity and Freedom

In the 1860 campaign for President, Lincoln firmly expressed his opposition to slavery and his determination to limit the expansion of slavery westward into the new territories acquired from Mexico in 1850. His election victory created a crisis for the nation, as many Southern Democrats feared that it would just be a matter of time before Lincoln would move to kill slavery in the South. Rather than face a future in which black people might become free citizens, much of the white South supported secession. This reasoning was based upon the doctrine of states' rights, which placed ultimate sovereignty with the states.

Lincoln vowed to preserve the Union even if it meant war. He eventually raised an army and navy of nearly three million Northern men to face a Southern army of more than two million soldiers. In battles fought from Virginia to California (but mainly in Virginia, in the Mississippi River Valley, and along the border states) a great civil war tore the United States apart. In pursuing victory, Lincoln assumed extralegal powers over the press, declared martial law in areas where no military action justified it, quelled draft riots with armed soldiers, and drafted soldiers to fight for the Union cause. No President in history had ever exerted so much executive authority, but he did so not for personal power but in order to preserve the Union. In 1864, as an example of his limited personal ambitions, Lincoln refused to call off national elections, preferring to hold the election even if he lost the vote rather than destroy the democratic basis upon which he rested his authority. With the electoral support of Union soldiers, many of whom were given short leaves to return home to vote, and thanks to the spectacular victory of Union troops in General Sherman's capture of Atlanta, Lincoln was decisively reelected.

What started as a war to preserve the Union and vindicate democracy became a battle for freedom and a war to end slavery when Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January of 1863. Although the Proclamation did not free all slaves in the nation—indeed, no slaves outside of the Confederacy were affected by the Proclamation—it was an important symbolic gesture that identified the Union with freedom and the death of slavery. As part of the Proclamation, Lincoln also urged black males to join the Union forces as soldiers and sailors. By the end of the war, nearly two hundred thousand African Americans had fought for the Union cause, and Lincoln referred to them as indispensable in ensuring Union victory.

Personal Tragedies and Triumphs

While the war raged, Lincoln also suffered great personal anguish over the death of his beloved son and the depressed mental condition of his wife, Mary. The pain of war and personal loss affected him deeply, and he often expressed his anguish by turning to humor and by speaking eloquently about the meaning of the great war which raged across the land. His Gettysburg Address, delivered after the Battle of Gettysburg, as well as his second inaugural in 1865, are acknowledged to be among the great orations in American history.

Almost all historians judge Lincoln as the greatest President in American history because of the way he exercised leadership during the war and because of the impact of that leadership on the moral and political character of the nation. He conceived of his presidential role as unique under the Constitution in times of crisis. Lincoln was convinced that within the branches of government, the presidency alone was empowered not only to uphold the Constitution, but also to preserve, protect, and defend it. In the end, however, Lincoln is measured by his most lasting accomplishments: the preservation of the Union, the vindication of democracy, and the death of slavery—accomplishments achieved by acting "with malice towards none" in the pursuit of a more perfect and equal union.

Michael Burlingame

Professor Emeritus of History Connecticut College

More Resources

Abraham lincoln presidency page, abraham lincoln essays, life in brief (current essay), life before the presidency, campaigns and elections, domestic affairs, foreign affairs, death of the president, family life, the american franchise, impact and legacy.

U.S. Presidents

Abraham lincoln.

16th president of the United States

Abraham Lincoln was born in a log cabin in Kentucky on February 12, 1809, to parents who could neither read nor write. He went to school on and off for a total of about a year, but he educated himself by reading borrowed books. When Lincoln was nine years old, his mother died. His father—a carpenter and farmer—remarried and moved his family farther west, eventually settling in Illinois .

As a young adult, Lincoln worked as a flatboat navigator, storekeeper, soldier, surveyor, and postmaster. At age 25 he was elected to the local government in Springfield, Illinois. Once there, he taught himself law, opened a law practice, and earned the nickname "Honest Abe."

He served one term in the U.S. House of Representatives but lost two U.S. Senate races. But the debates he had about the enslavement of people with his 1858 senatorial opponent, Stephen Douglas, helped him win the presidential nomination two years later. (Lincoln opposed the spread of slavery in the United States .) In the four-way presidential race of 1860, Lincoln got more votes than any other candidate.

A NATION DIVIDED

When Lincoln first took office in 1861, the United States was not truly united. The nation had been arguing for years about enslaving people and each state’s right to allow it. Now Northerners and Southerners were close to war. When he became president, Lincoln allowed the enslavement of people to continue in southern states but he outlawed its spread to other existing states and states that might later join the Union.

Southern leaders didn’t agree with this plan and decided to secede, or withdraw, from the nation. Eventually, 11 southern states formed the Confederate States of America to oppose the 23 northern states that remained in the Union. The Civil War officially began on April 12, 1861, at Fort Sumter, South Carolina , when troops from the Confederacy attacked the U.S. fort.

WARTIME PRESIDENCY

Lincoln’s primary goal as president was to hold the country together. For a long time, it didn’t look as if he would succeed. During the early years, the South was winning the war. It wasn’t until the Battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania during July 1863 that the war turned in favor of the Union.

Through speeches such as the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln encouraged Northerners to keep fighting. In this famous dedication of the battlefield cemetery, he urged citizens to ensure "that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth." Earlier that same year Lincoln called for the end of the enslavement of people in his Emancipation Proclamation speech.

When the war was nearly over, Lincoln was re-elected in 1864. Civil War victory came on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, when Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant. Some 750,000 soldiers had died during the four-year conflict.

OTHER ACCOMPLISHMENTS

Seeing the Union successfully through the Civil War was Lincoln’s greatest responsibility, but it wasn’t his only triumph during his presidential years. Together with Congress, he established the Department of Agriculture; supported the development of a transcontinental railroad; enacted the Homestead Act, which opened up land to settlers; and crafted the 13th Amendment, which ended the enslavement of people.

TRAGIC FATE

Less than a week after people celebrated the end the Civil War, the country was mourning yet again. Lincoln became the first president to be assassinated when he was shot on April 14, 1865.

The night he was shot, he and his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, were watching a play in Washington, D.C. The entrance to their box seats was poorly guarded, allowing actor John Wilkes Booth to enter. Booth hoped to revive the Confederate cause by killing Lincoln. He shot Lincoln in the back of the head, then fled the theater. He wasn’t caught until two weeks later. He was shot during his eventual capture and died from his wounds.

The wounded and unconscious president was carried to a boardinghouse across the street, where he died the next morning, April 15, 1865. Lincoln’s presidency was tragically cut short, but his contributions to the United States ensured that he would be remembered as one of its most influential presidents.

• The Lincoln family ate at the White House dinner table with their cat.

• Lincoln sometimes kept important documents under the tall black hats he wore.

• Lincoln was taller (at six feet four inches) than any other president.

From the Nat Geo Kids books Our Country's Presidents by Ann Bausum and Weird But True Know-It-All: U.S. Presidents by Brianna Dumont, revised for digital by Avery Hurt

read this next

(ad) "weird but true know-it-all: u.s. presidents", independence day, (ad) "our country's presidents".

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your California Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell My Info

- National Geographic

- National Geographic Education

- Shop Nat Geo

- Customer Service

- Manage Your Subscription

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Humanities ›

- History & Culture ›

- American History ›

- U.S. Presidents ›

Biography of Abraham Lincoln, 16th President of the United States

Wikimedia Commons

- U.S. Presidents

- Important Historical Figures

- Native American History

- American Revolution

- America Moves Westward

- The Gilded Age

- Crimes & Disasters

- The Most Important Inventions of the Industrial Revolution

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- M.A., History, University of Florida

- B.A., History, University of Florida

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809–April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 to 1865. During his time in office, the nation fought the Civil War, which claimed hundreds of thousands of lives. One of Lincoln's greatest accomplishments was the abolition of enslavement in 1864.

Fast Facts: Abraham Lincoln

- Known For : U.S. president from March 4, 1861–March 3, 1865; issued Emancipation Proclamation in 1862, freeing enslaved people in the southern United States

- Also Known As : Honest Abe

- Born : February 12, 1809 in Sinking Spring Farm, Kentucky

- Died : April 15, 1865 in Washington, D.C.

- Spouse : Mary Todd Lincoln (m. 1842–1865)

- Children : Robert, Edward, Willie, Tad

- Notable Quote : "Whenever I hear anyone arguing for slavery, I feel a strong impulse to see it tried on him personally."

Abraham Lincoln was born in Hardin County, Kentucky, on February 12, 1809. He moved to Indiana in 1816 and lived there for the rest of his youth. His mother died when he was 9 but he was very close to his stepmother, who urged him to read. Lincoln himself stated that he had about one year of formal education. However, he was taught by many different individuals. He loved to read and learn from any books he could get his hands on.

On November 4, 1842, Lincoln married Mary Todd . She had grown up in relative wealth. Many historians believe that Todd was mentally unbalanced ; she struggled with mental health issues throughout her life and may have suffered from bipolar disorder. The Lincolns had four children, all but one of whom died young. Edward died at age 3 in 1850. Robert Todd grew up to be a politician, lawyer, and diplomat. William Wallace died at the age of 12. He was the president's only child to die in the White House. Thomas "Tad" died at 18.

Military Career

In 1832, Lincoln enlisted to fight in the Black Hawk War. He was quickly elected captain of a company of volunteers. His company joined regulars under Colonel Zachary Taylor . Lincoln only served 30 days in this capacity and then signed on as a private in the Mounted Rangers. He then joined the Independent Spy Corps. He saw no real action during his short stint in the military.

Political Career

Lincoln worked as a clerk before joining the military. He ran for the Illinois state legislature and lost in 1832. He was appointed as postmaster of New Salem, Illinois by Andrew Jackson and later elected as a Whig to the state legislature, where he served from 1834 to 1842. Lincoln studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1836. From 1847 to 1849 he served as a U.S. Representative in Congress. He was elected to the state legislature in 1854 but resigned to run for the U.S. Senate. He gave his famous "house divided" speech after being nominated.

Lincoln-Douglas Debates

Lincoln debated his opponent for the Senate seat, Stephen Douglas , seven times in what became known as the Lincoln-Douglas Debates . While they agreed on many issues, the two disagreed over the morality of enslavement. Lincoln did not believe that enslavement should be allowed to spread any further through the United States, while Douglas argued for popular sovereignty . Lincoln explained that while he was not asking for equality, he believed African Americans should receive the rights granted to all Americans in the Declaration of Independence : life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Lincoln lost the election to Douglas.

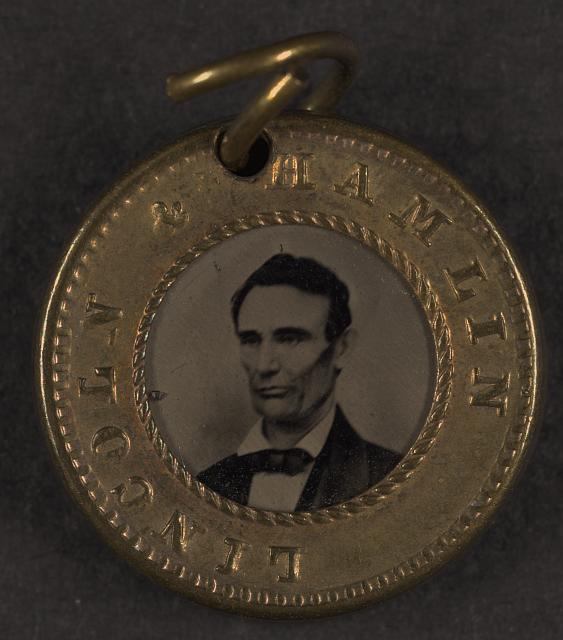

Presidential Election

In 1860, Lincoln was nominated for the presidency by the Republican Party with Hannibal Hamlin as his running mate. He ran on a platform denouncing disunion and calling for an end to enslavement in the territories. The Democrats were divided, with Stephen Douglas representing the Democrats and John Breckinridge the National (Southern) Democrats nominee. John Bell ran for the Constitutional Union Party, which took away votes from Douglas. In the end, Lincoln won 40% of the popular vote and 180 of the 303 electoral college votes. Since he was in a four-way race, this was enough to ensure his victory.

First Presidential Term

The main event of Lincoln's presidency was the Civil War, which lasted from 1861 to 1865. Eleven states seceded from the Union , and Lincoln firmly believed in the importance of not only defeating the Confederacy but also reuniting North and South to preserve the Union.

In September 1862, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. This declaration freed enslaved Americans in all the Southern states. In 1864, Lincoln promoted Ulysses S. Grant to commander of all Union forces.

The Republicans, at this point called the National Union Party, had some concern that Lincoln wouldn't win but still renominated him for a second term with Andrew Johnson as his vice president. Their platform demanded unconditional surrender and an official end to enslavement. Challenger George McClellan had been relieved as the head of the Union armies by Lincoln. His platform was that the war was a failure, and Lincoln had taken away too many civil liberties . Lincoln won reelection after the war turned in the North's favor.

In April 1865, Richmond fell and Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse . In the end, the war was the most costly in American history and also the bloodiest, with hundreds of thousands of casualties. Enslavement was forever ended with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment.

On April 14, 1865, Lincoln was assassinated while attending a play at Ford's Theater in Washington, D.C. Actor John Wilkes Booth shot him in the back of the head before jumping onto the stage and escaping to Maryland. Lincoln died on April 15 and was buried in Springfield, Illinois.

On April 26, Booth was found hiding in a barn, which was set on fire. He was then shot and killed. Eight conspirators were punished for their roles in the plot to kill the president.

Lincoln is considered by many scholars to be one of the most accomplished and successful presidents in United States history. He is credited with holding the Union together and leading the North to victory in the Civil War . Furthermore, his actions led to the emancipation of African Americans from the bonds of enslavement.

- Donald, David Herbert. "Lincoln." Niagara, 1996.

- Gienapp, William E. "Abraham Lincoln and Civil War America: a Biography." Oxford University Press, 2002.

- How the Obama and Lincoln Presidencies Were Similar

- Abe Lincoln and His Ax: Reality Behind the Legend

- Biography of Andrew Johnson, 17th President of the United States

- Biography of James Buchanan, 15th President of the United States

- Abraham Lincoln: Facts and Brief Biography

- Quotes from Abraham Lincoln

- Which Presidents Were Republican?

- The Lincoln-Douglas Debates of 1858

- Was Abraham Lincoln Really a Wrestler?

- 10 Facts to Know About Andrew Johnson

- Abraham Lincoln's Greatest Speeches

- Timeline: Early Life of Abraham Lincoln

- The Five Best Inaugural Addresses of the 19th Century

- How Many U.S. Presidents Have Been Assassinated?

- 10 of the Most Influential Presidents of the United States

- Presidents Who Served After the Civil War

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

Abraham Lincoln — Facts, Information and History on the Life of the 16th U.S. President

Facts, information and articles about the life of abraham lincoln, 16th president of the united states, abraham lincoln facts.

February 12, 1809, Hodgenville, Kentucky

April 15, 1865, Petersen House, Washington, D.C.

Presidential Term

March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865

Mary Todd Lincoln

Major accomplishments.

Served Four Terms in Illinois Legislature

Member of U.S. House of Representatives

16th President of the United States

Commander in Chief During Civil War

Abraham Lincoln Pictures

View Pictures, Photographs and Images of Abraham Lincoln throughout his life. View Abraham Lincoln Pictures .

Abraham Lincoln Movies

See a list of movies and videos of the life of Abraham Lincoln. View Abraham Lincoln Movies .

Abraham Lincoln Articles

Explore articles from the HistoryNet archives about Abraham Lincoln

Articles Featuring Abraham Lincoln From HistoryNet Magazines

» See all Abraham Lincoln Articles

Abraham Lincoln Summary

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th president of the United States of America, who successfully prosecuted the Civil War to preserve the nation. He played in key role in passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which officially ended slavery in America. Murdered by John Wilkes Booth , Lincoln became the first U.S. president to be assassinated. Prior to his election as president in 1860, he had successful careers as a lawyer and politician in Illinois, serving several terms in the state legislature and one in the U.S. House of Representatives. He also holds the distinction of being the only U.S. president to receive a patent; in 1849, he designed a system for lifting riverboats off sandbars.

Abraham Lincoln’s Life: Youth

Abraham Lincoln was born on Sinking Springs Farm near Hodgenville, Kentucky, on February 12, 1809, to Thomas and Nancy Hanks Lincoln. He was named for his paternal grandfather. His birthplace is believed to have been a 16-foot by 18-foot log cabin, which no longer exists. Lincoln had a sister, Sarah, who was two years and two days older than he was, and a younger brother, Thomas, who died in infancy.

When Abraham was two, the family moved to nearby Knob Creek Farm. Five years later, the family moved again, to the wilderness on Little Pigeon Creek in Indiana. On October 5, 1818, his mother died, reportedly of “milk sickness,” caused by drinking milk from cows that have eaten a poisonous, blossoming plant called snakeroot. Thomas Lincoln remarried a year later, to Sarah Bush Johnston, a woman of Elizabethtown, Kentucky, whom he had known for many years. She had three children by a previous marriage, Elizabeth, Matilda, and John. Although Abraham and his father were never close, Sarah and nine-year-old Abraham formed a loving relationship that continued throughout their lives. She encouraged him in his attempts to educate himself, which he did by borrowing and studying books.

Lincoln Moves To Illinois

In 1830, when Abraham was 21, the family moved to Illinois. He performed odd jobs and took a flatboat of goods to New Orleans. At New Salem, he was a partner in a store at that failed and would be many years paying off the last of the store’s creditors, an obligation he referred to as “the National Debt.” Elected captain of a militia unit during the 1832 Black Hawk War —an election he later would say pleased him more than any other—he saw no combat, but he met the man who would change his life in many ways: John Todd Stuart.

Lincoln Becomes A Lawyer

Stuart and Lincoln both ran for the Illinois General Assembly that year; Stuart won, Lincoln didn’t. Two years later, however, both men won election. The more experienced Stuart, known as “Jerry Sly” for his skills at management and intrigue, showed Lincoln the ropes and loaned him law books, that he might study to become an attorney. In 1836, Lincoln received a license to practice law. He would go on to establish a respectable record as an attorney and was often hired by the Illinois Central Railroad.

Lincoln won reelection to the General Assembly in 1836, 1838, and 1840; among his accomplishments was a major role in getting the state capital moved to Springfield. He did not actively seek the post again after 1840, but won the popular vote in 1854; however, he resigned so he would be eligible for election to the U.S. Senate.

Lincoln Goes To Congress

In 1846, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, where he gave the infamous “Spot” speech about the war that had begun with Mexico. He demanded President James K. Polk reveal the exact spot on which American blood had been shed, starting the war, and whether that spot was on American or Mexican soil.

The speech may have been a reflection of words his “beau ideal” statesman, Speaker of the House Henry Clay, had uttered in a speech Lincoln heard while visiting Lexington, Kentucky, on the way to Washington. Or it may have been a partisan maneuver—Lincoln was a Whig, Polk a Democrat—to ingratiate himself with the older Whigs in Washington. Popular opinion in most of the country supported the war, and newspapers around the country ridiculed him as “Spotty Lincoln.” He did not run for reelection to Congress in 1848, but for the first time in its history, his home district elected a Democrat instead of a Whig. He spent the next several years focusing on his law practice to support his growing family.

In the Illinois legislature, he’d served with Ninian Wirt Edwards of Springfield, the son of a former governor of Illinois. Edwards’ wife was the former Elizabeth Todd of Lexington, Kentucky. When her younger sister, Mary, came from Lexington Lincoln became smitten; as Ninian observed, “Mary could make a bishop forget his prayers.” Although facts are unclear, an understanding apparently developed between Lincoln and Mary, but they parted ways in December of 1840 or January of 1841. Over a year later, a friend brought them back together, and they wed November 4, 1842.

There have long been stories—begun by Lincoln’s long-time law partner, William Herndon—that Lincoln had previously been engaged to Ann Rutledge in New Salem and had nearly lost his mind when she died. However, she was betrothed to another and there is no verifiable evidence of any romantic relationship or understanding between her and Lincoln. Neighbors’ stories indicate Lincoln did take her death hard. He was always prone to fits of “melancholia”—depression—and one state legislator claimed Lincoln told him he wouldn’t carry a pocket knife for fear he’d use it to harm himself.

Family Life With Mary Todd Lincoln

Abraham and Mary Lincoln would produce four children: Robert Todd, named for Mary’s father; Edward (Eddie) Baker, named for a close friend; William (Willie) Wallace, named for Dr. William Wallace, who had married Francis, another Todd sister, and had become close friends with Lincoln; and Thomas (Tad), named for Lincoln’s father who had died two years earlier. Eddie died in 1850, Willie in 1862, and Tad in 1871. Only Robert lived to adulthood; the last of his descendants would die in 1985, ending the Abraham Lincoln family line. (Learn more about Mary Todd Lincoln )

Although Lincoln did not seek office himself during these years, he remained active in the Whig Party, counseling candidates who sought his advice and occasionally responding to speaking requests. In 1854, he essentially was campaign manager for Richard Yates, who was running for the General Assembly. Lincoln did not want to be elected to that body again himself because he knew the legislature would be electing a new U.S. Senator during its coming term, to fill the position of James Shields, who had moved to the Minnesota Territory. (At that time, nearly 60 years before the Seventeenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provided for direct election of senators by the voters, they were chosen by each state’s legislature.) By Illinois law, sitting state legislators could not be elected to the U.S. Congress—and Lincoln desperately wanted to become the new senator, a position he said he would prefer over being president. Regardless, eventually he reluctantly agreed to run . He won more votes than any other candidate but resigned in order to keep his senatorial chances open.

His hopes were dashed again when the vote for senator was taken in 1857. Despite a strong start, he saw that a Democrat would be elected unless the Whigs united, so he threw his supporters’ votes to another candidate.

Since the early 1830s, abolitionists—those who adamantly favored abolishing slavery everywhere in the United States—had become increasingly strident. Even many people like Lincoln who did not approve of slavery also did not approve of the sectional divisiveness engendered by the abolitionists. Slaveholding states—virtually all of which were in the South—in responding to abolitionists’ attacks defended the “peculiar institution” of slavery more vociferously, and sectional tensions grew.

A Nation Dividing

In 1854, a passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act allowed residents of any new states admitted to the Union to decide for themselves whether or not the state would be free or slaveholding. In the 1857 Dred Scott decision the Supreme Court ruled that neither the Declaration of Independence nor the rights guaranteed by the Constitution applied to Negroes and never had. As a result of these events, many who had disassociated themselves with abolitionists’ agitation began drifting into their camp, and the abolitionists movement intensified.

Like his father, Lincoln opposed slavery; however, he also deplored abolitionists’ activities because they threatened to cause a schism in the nation. In regard to “slavery agitation” he said, “In my opinion, it will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached, and passed. ‘A house divided against itself cannot stand'”

Notes for a speech he delivered in Ohio clearly articulate his opinions on the slavery issue in the 1850s:

“We must not disturb slavery in the states where it exists, because the Constitution, and the peace of the country both forbid us – We must not withhold an efficient fugitive slave law, for the constitution demands it – But we must, by a national policy, prevent the spread of slavery into new territories, or free states, because the constitution does not forbid us, and the general welfare does demand such prevention.” (Abraham Lincoln, (September 16–17, 1859), Notes for Speech in Kansas and Ohio)

The Whig Party to which he had always been dedicated was dying. By 1854, a new party, the Republicans, was taking its place. Comprised of old Whigs, disaffected Democrats and members of the Native American Party (“Know-Nothings”), its unifying theme was opposition to the institution of slavery. In 1856, Lincoln joined the new party.

The Lincoln Douglas Debates

In 1858, he engaged in a legendary series of debates across Illinois with the author of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Sen. Stephen Douglas. The five-foot, four-inch Douglas—”the Little Giant”—and the lanky, six-foot-four Lincoln faced off over the issue of expanding slavery beyond the states where it currently existed. Lincoln carefully made a distinction between slavery where it existed and its expansion into new territories and states. The debates grew national attention, and Lincoln was invited to speak in other states. (Read more about the Lincoln Douglas Debates )

The national attention he received resulted in the Republican Party making him its presidential candidate in the 1860 election. On the divisive matter of slavery, the Republican platform supported prohibiting slavery in the territories but opposed interfering with it in the states where it already existed.