72 Dog Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

To find good research titles for your essay about dogs, you can look through science articles or trending pet blogs on the internet. Alternatively, you can check out this list of creative research topics about dogs compiled by our experts .

🐩 Dog Essays: Things to Consider

🏆 best dog titles for essays, 💡 most interesting dog topics to write about, ❓ questions about dog.

There are many different dog essays you can write, as mankind’s history with its best friends is rich and varied. Many people will name the creatures their favorite animals, citing their endearing and inspiring qualities such as loyalty, obedience, bravery, and others.

Others will discuss dog training and the variety of important roles the animals fulfill in our everyday life, working as shepherds, police members, guides to blind people, and more.

Some people will be more interested in dog breeding and the incredible variety of the animals show, ranging from decorative, small Yorkshire terriers to gigantic yet peaceful Newfoundland dogs. All of these topics are interesting and deserve covering, and you can incorporate all of them a general essay.

Dogs are excellent pet animals, as their popularity, rivaled only by cats, shows. Pack animals by nature, they are open to including members of other species into their groups and get along well with most people and animals.

They are loyal to the pack, and there are examples of dogs adopting orphaned kittens and saving other animals and children from harm.

This loyalty and readiness to face danger makes them favorite animals for many people, and the hundreds of millions of dogs worldwide show that humans appreciate their canine friends.

It also allows them to work many important jobs, guarding objects, saving people, and using their noses to sniff out various trails and substances.

However, dogs are descended from wolves, whose pack nature does not prevent them from attacking those outside the group. Some larger dogs are capable of killing an adult human alone, and most can at least inflict severe harm if they attack a child.

Dogs are trusted and loved because of their excellent trainability. They can be taught to be calm and avoid aggression or only attack once the order is given.

They can also learn a variety of other behaviors and tricks, such as not relieving themselves in the house and executing complex routines. This physical and mental capacity to perform a variety of tasks marks dogs as humanity’s best and most versatile helpers.

The variety of jobs dogs perform has led humans to try to develop distinct dog breeds for each occupation, which led to the emergence of numerous and different varieties of the same animal.

The observation of the evolution of a specific type of dog as time progressed and its purposes changed can be an interesting topic. You can also discuss dog competitions, which try to find the best dog based on various criteria and even have titles for the winners.

Comparisons between different varieties of the animal are also excellent dog argumentative essay topics. Overall, there are many interesting ideas that you can use to write a unique and excellent essay.

Regardless of what you ultimately choose to write about, you should adhere to the central points of essay writing. Make sure to describe sections of your paper with dog essay titles that identify what you will be talking about clearly.

Write an introduction that identifies the topic and provides a clear and concise thesis statement. Finish the paper with a dog essay conclusion that sums up your principal points. It will be easier and more interesting to read while also adhering to literature standards if you do this.

Below, we have provided a collection of great ideas that you can use when writing your essays, research papers, speeches, or dissertations. Take inspiration from our list of dog topics, and don’t forget to check out the samples written by other students!

- An Adventure with My Pet Pit-Bull Dog “Tiger” One look at Tiger and I knew that we were not going to leave the hapless couple to the mercies of the scary man.

- Dogs Playing Poker The use of dogs in the painting is humorous in that the writer showed them doing human things and it was used to attract the attention of the viewer to the picture.

- “Love That Dog” Verse Novel by Sharon Creech In this part of the play, it is clear that Jack is not ready to hide his feelings and is happy to share them with someone who, in his opinion, can understand him.

- Compare and Contrast Your First Dog vs. Your Current Dog Although she was very friendly and even tried to take care of me when I was growing up, my mother was the real owner.

- The Benefits of a Protection Dog Regardless of the fact that protection dogs are animals that can hurt people, they are loving and supportive family members that provide their owners with a wide range of benefits.

- “Marley: A Dog Like No Other” by John Grogan John Grogan’s international bestseller “Marley: A Dog Like No Other” is suited for children of all ages, and it tells the story of a young puppy, Marley, who quickly develops a big personality, boundless energy, […]

- Cesar Millan as a Famous Dog Behaviorist Millan earned the nickname “the dog boy” because of his natural ability to interact with dogs. Consequently, the dog behaviorist became a celebrity in different parts of the country.

- “Dog’s Life” by Charlie Chaplin Film Analysis In this film, the producer has used the comic effect to elaborate on the message he intends to deliver to the audience. The function of a dog is to serve the master.

- Dog’ Education in “The Culture Clash” by Jean Donaldson The second chapter comes under the title, Hard-Wiring: What the Dog comes with which tackles the characteristic innate behaviors that dogs possess naturally; that is, predation and socialization. This chapter sheds light on the behaviors […]

- Debates on Whether Dog is the Best Pet or not The relationships between dogs and man have been improving over the years and this has made dogs to be the most preferable pets in the world. Other pets have limited abilities and can not match […]

- Cats vs. Dogs: Are You a Cat or a Dog Person? Cats and dogs are two of the most common types of pets, and preferring one to another can arguably tell many things about a person.

- How to Conduct the Dog Training Properly At the same time, it is possible to work with the dog and train it to perform certain actions necessary for the owner. In the process of training, the trainer influences the behavior of the […]

- Dog Food: Pedigree Company’s Case The attractiveness of the dog food category is manifested through the intense competitive nature of the various stakeholders. The third and final phase of the segmentation is to label the category of dog food as […]

- Operant Conditioning in Dog Training In regards to negative enforcements, the puppy should be fitted with a collar and upon the command “sit”, the collar should be pulled up a bit to force the dog to sit down.

- The “This Is Fine” Dog Meme Analysis In 2020, the meme was repurposed to reflect the COVID-19 pandemic, with the dog wearing a mask and saying, “This is fine”.

- Dog Ownership’s Benefits for Cardiovascular Health According to the American Heart Association, dog owners are 54% more likely to meet the recommended levels of physical activity than the average person without a pet.

- Dog Training Techniques Step by Step The first step that will be taken in order to establish the performance of this trick is showing the newspaper to the dog, introducing the desired object and the term “take”.

- The Great Pyrenees Dog Breed as a Pet In the folklore of the French Pyrenees, there is a touching legend about the origin of the breed. The dog will not obey a person of weak character and nervous.

- Dog Food by Subscription: Service Design Project For the convenience and safety of customers and their dogs, customer support in the form of a call center and online chat is available.

- “Everyday” in The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Haddon The novel presents Christopher who passes through many changes in his life, where he adapts to it and acclimatizes the complications that come with it.

- A Dog’s Life by Charles Chaplin The theme of friendship and love that is clear in the relationship between Tramp and Scraps. The main being that Chaplin makes it very comical thus; it is appealing to the audience, and captures the […]

- Why Does Your Dog Pretend to Like You? Children and the older generation can truly cherish and in the case of children can develop as individuals with the help of dogs.

- Caring for a Dog With Arthritis For Monty, the dog under study, the size, and disposition of the dog, the stage of the disease as also its specific symptoms and behaviour need to be observed and then a suitable choice of […]

- Animal Cruelty: Inside the Dog Fighting In most cases the owner of the losing dog abandons the injured dog to die slowly from the injuries it obtained during the fight. The injuries inflicted to and obtained by the dogs participating in […]

- “Traditional” Practice Exception in Dog Act One of those who wanted the word to remain in the clause was the president of the Beaufort Delta Dog Mushers and also an Inuvik welder.Mr.

- Small Dog Boarding Business: Strategic Plan Based on the first dimension of the competing values framework, the dog boarding business already has the advantage of a flexible business model, it is possible to adjust the size of the business or eliminate […]

- Small Dog Boarding Business: Balanced Scorecard Bragonier posits that SWOT analysis is essential in the running of the business because it helps the management to analyze the business at a glance.

- Non-Profit Dog Organization’s Mission Statement In terms of the value we are bringing, our team regards abandoned animals who just want to be loved by people, patients with special needs, volunteers working at pet shelters, and the American society in […]

- Breed Specific Legislation: Dog Attacks As a result, the individuals that own several canines of the “banned” breeds are to pay a lot of money to keep their dogs.

- Implementing Security Policy at Dog Parks To ensure that people take responsibility for their dogs while in the parks, the owners of the parks should ensure that they notify people who bring their dogs to the park of the various dangers […]

- First in Show Pet Foods, Inc and Dog Food Market Due to the number of competitors, it is clear that First in Show Pet Food, Inc.understands it has a low market share.

- Animal Assisted Therapy: Therapy Dogs First, the therapist must set the goals that are allied to the utilization of the therapy dog and this should be done for each client.

- The Tail Wagging the Dog: Emotions and Their Expression in Animals The fact that the experiment was conducted in real life, with a control group of dogs, a life-size dog model, a simultaneous observation of the dogs’ reaction and the immediate transcription of the results, is […]

- Moral Dilemma: Barking Dog and Neighborhood Since exuberant barking of Stella in the neighborhood disturbs many people, debarking is the appropriate measure according to the utilitarian perspective.

- The Feasibility Analysis for the Ropeless Dog Lead This is because it will have the ability to restrict the distance between the dog and the master control radio. The exploration of different sales models and prices for other devices indicates that the Rope-less […]

- Classical Conditioning: Teaching an Old Dog New Tricks According to Basford and Stein’s interpretation, classical conditioning is developed in a person or an animal when a neutral stimulus “is paired or occurs contingently with the unconditioned stimulus on a number of occasions”, which […]

- The Movements and Reactions of Dogs in Crates and Outside Yards This study discusses the types of movements and reactions exhibited by dogs in the two confinement areas, the crate and the outside yard.

- A Summary of “What The Dog Saw” Gladwell explores the encounters of Cesar Millan, the dog whisperer who non-verbally communicated with the dogs and mastered his expertise to tame the dogs.

- Border Collie Dog Breed Information So long as the movement of the Border Collies and the sheep is calm and steady, they can look for the stock as they graze in the field.

- Evolution of Dogs from the Gray Wolf However, the combined results of vocalisation, morphological behavior and molecular biology of the domesticated dog now show that the wolf is the principle ancestor of the dog.

- The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time Haddon therefore manages to carry the reader into the world of the novel and holds the reader to the end of the novel.

- Attacking Dog Breeds: Truth or Exaggeration?

- Are Bad Dog Laws Unjustified?

- Are Dog Mouths Cleaner Than Humans?

- Can Age Affect How Fast a Dog Runs?

- Can Chew Treats Kill Your Dog?

- Can You Control Who the Alpha Dog Is When You Own Two Dogs?

- Does Drug Dog Sniff Outside Home Violate Privacy?

- Does the Pit Bull Deserve Its Reputation as a Vicious Dog?

- Does Your Dog Love You and What Does That Mean?

- Does Your Dog Need a Bed?

- How Can People Alleviate Dog Cruelty Problems?

- How Cooking With Dog Is a Culinary Show?

- How Can Be Inspiring Dog Tales?

- How Owning and Petting a Dog Can Improve Your Health?

- How the I-Dog Works: It’s All About Traveling Signals?

- What Can Andy Griffith Teach You About Dog Training?

- What Makes the Dog – Human Bond So Powerful?

- What the Dog Saw and the Rise of the Global Market?

- What Should You Know About Dog Adoption?

- When Dog Training Matters?

- When Drug Dog Sniff the Narcotic Outside Home?

- At What Age Is Dog Training Most Effective?

- Why Are People Choosing to Get Involved in Dog Fighting?

- Why Are Reported Cases of Dog-Fighting Rising in the United States?

- Why Dog Attacks Occur and Who Are the Main Culprits?

- Why Does Dog Make Better Pets Than Cats?

- Why Every Kid Needs a Dog?

- Why Should People Adopt Rather Than Buy a Dog?

- Why Could the Dog Have Bitten the Person?

- Will Dog Survive the Summer Sun?

- Animal Rights Research Ideas

- Inspiration Topics

- Animal Welfare Ideas

- Wildlife Ideas

- Emotional Development Questions

- Zoo Research Ideas

- Endangered Species Questions

- Human Behavior Research Topics

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 26). 72 Dog Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/dog-essay-examples/

"72 Dog Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 26 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/dog-essay-examples/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '72 Dog Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 26 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "72 Dog Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/dog-essay-examples/.

1. IvyPanda . "72 Dog Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/dog-essay-examples/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "72 Dog Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." February 26, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/dog-essay-examples/.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Current perspectives on attachment and bonding in the dog–human dyad

Elyssa payne, pauleen c bennett, paul d mcgreevy.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence: Elyssa Payne, RMC Gunn Building, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia, Tel +61 4 0222 5335, Email [email protected]

Collection date 2015.

The full terms of the License are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ . Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed.

This article reviews recent research concerning dog–human relationships and how attributes that arise from them can be measured. It highlights the influence of human characteristics on dog behavior, and consequently, the dog–human bond. Of particular importance are the influences of human attitudes and personality. These themes have received surprisingly little attention from researchers. Identifying human attributes that contribute to successful dog–human relationships could assist in the development of a behavioral template to ensure dyadic potential is optimized. Additionally, this article reveals how dyadic functionality and working performance may not necessarily be mutually inclusive. Potential underpinnings of various dog–human relationships and how these may influence dogs’ perceptions of their handlers are also discussed. The article considers attachment bonds between humans and dogs, how these may potentially clash with or complement each other, and the effects of different bonds on the dog–human dyad as a whole. We review existing tools designed to measure the dog–human bond and offer potential refinements to improve their accuracy. Positive attitudes and affiliative interactions seem to contribute to the enhanced well-being of both species, as reflected in resultant physiological changes. Thus, promoting positive dog–human relationships would capitalize on these benefits, thereby improving animal welfare. Finally, this article proposes future research directions that may assist in disambiguating what constitutes successful bonding between dogs and the humans in their lives.

Keywords: human–animal bond, personality, attitudes, social learning, affective state, dog

Introduction

Symbiotic relationships between dogs and humans are thought to date back at least 18,000 years. 1 Although it has been argued that the tendency for dogs to form close relationships with humans can be attributed to social dominance, with dogs seeing humans as surrogate pack leaders, 2 social and associative learning appear highly relevant to dog–human interactions. 3 – 5 Dogs seem to possess an ability to interpret and respond to human signaling that exceeds that of chimpanzees. 6 – 8 The proficiency of dogs and extensively socialized wolves at such tasks is thought to reflect their adeptness at social scavenging or cooperation and associating certain human gestures with the provision of food, both of which can facilitate rapid learning. 9 , 10 These days, dogs are used in various contexts that exploit their responsiveness to human direction, such as security work, moving livestock, and assisting humans with disabilities. It may be argued that working dog–human relationships are unidirectional, as they depend only on the function the dog performs. However, given that relational factors can affect dog performance, 11 it is likely that, as with companion dog–owner relationships, these relationships are bidirectional. 12 In light of this, the current article will discuss dog–human relationships on a general level, with particular emphasis on companion dogs and their owners.

An attachment bond is a close, emotional relationship between two individuals. 13 The dog–human dyad is believed to involve attachment bonds similar to those that characterize human caregiver–infant relationships. 14 Dogs have shown behaviors indicative of an attachment relationship, defined according to Bowlby. 13 One such behavior is proximity seeking, where the animal will seek out the attachment figure as a means of coping with stress. 15 Conversely, the absence of an attachment figure can trigger behaviors indicative of separation-related distress in dogs. 16 The presence of a human can also attenuate the effect of a stressful event, thereby constituting the so-called safe haven effect of attachment theory. 17 Dogs have also demonstrated the so-called secure base effect, where the presence of an attachment figure allows dogs to more freely investigate novel objects. 18 Therefore, the dog–human attachment bond is characterized by all four features of attachment bonds that arise in human caregiver–infant relationships. Moreover, there is some evidence of interactions between owner and dog attachment patterns, 19 although this is disputed. 20 What remains unknown are the factors that influence the nature of attachment bonds dogs develop with their human handlers or owners. If certain attachment styles are beneficial in different working dog contexts, human behaviors could be tailored accordingly to produce more functional dyads.

Human factors that contribute to dog behavior and training outcomes are the focus of a growing body of research. Several of these factors are likely to influence dogs’ affective, or emotional, states and thereby influence their behavioral output. Many human interventions, such as use of positive reinforcement 21 and affiliative interactions, 22 are likely to produce a positive affective state in a dog, leading to more favorable behavioral responses, such as obedience during training. However, it is important to note that expert timing of these interventions is essential for training success. 23 Hence, the expert application of such attributes is suitable for encouraging certain behaviors in dogs and likely contributes to a positive emotional bond. Focusing on improving these characteristics offers a promising solution for dog owners with relatively suboptimal dog-handling ability, or dogmanship, defined as an individual’s ability to interact with and train dogs. However, the influence of human psychological characteristics, such as personality and attitudes, on dogmanship and the dog–human relationship remains unclear. Thus far, the tantalizing notion that certain personality dimensions may predispose an individual to interact skillfully with dogs remains unconfirmed.

The physiological and emotional benefits that ensue from a positive dog–human relationship extend to both members of the dyad. For dogs, humans seem to represent a social partner that, in addition to providing information pertinent to food acquisition, can be a source of emotional fulfilment and attachment. 16 Similarly, forming relationships with, or simply interacting with, dogs has been associated with several emotional and psychological health benefits for humans. 24 , 25 Hence, fostering secure, positive emotional bonds between humans and dogs generally promotes well-being. This article aims to review current literature on the dog–human relationship, especially that regarding attachment and bonding. Assessing dog–human relationships through the use of a scientifically validated tool may reveal which dyads successfully capitalize on mutual benefits and those that may require intervention. This article will review existing tools designed to measure the dog–human bond. Including all possible measures of dog–human relationships, especially those that focus only on a singular aspect of these relationships, such as dog–human attachment, is well beyond the scope of this article (for reviews see Wilson and Netting 26 and Anderson 27 ). So, we will attempt to focus primarily on those measures that reflect a significant portion of the dog–human relationship.

A greater understanding of the mechanisms of well-matched dog–human dyads may foster the promotion of successful dyads through the skillful application of certain behaviors on the part of the human. Moreover, this may reduce the incidence of dysfunctional dog–human relationships, which can be harmful to both dyadic members, 28 , 29 as well as the broader community. 30

Perceptions and attitudes of dog owners towards dogs

The influence of owner attitudes to or viewpoints on dog behavior and welfare represents a relatively recent avenue of research. Dogs belonging to those who regard their animals as social partners or meaningful companions have been shown to have relatively low salivary cortisol concentrations. 15 This suggests that positive owner attitudes may moderate stress in canine companions. Furthermore, Norwegian dog owners with more positive attitudes towards their dogs also had higher animal empathy scores, which correlated with how they rated pain in dogs. 31 Hence, empathetic dog owners with positive attitudes may be more aware of pain in their animal and readily respond to it, thus minimizing stress. Such handlers may have what Blouin described as humanistic views of their animals, regarding them as surrogate humans that offer affective benefits, or protectionistic views of their animals, regarding them as valuable companions with their own interests. 32 Blouin also identified a third perspective, dominionistic, whereby animals are viewed with low regard and valued only for their usefulness. 32 One would predict that dominionistic handlers would have less positive attitudes towards their pets, and consequently, the affective benefits to either dog or human may be limited.

Some sheepdog handlers reportedly regard dogs dominionistically, as tools that will eagerly please the pack leader (the human) by driving stock towards them. 33 More plausibly, the dogs in question drive stock chiefly because this is a self-rewarding behavior. 23 Similarly, it has been reported that dog handlers often misinterpret several aspects of their dog’s behavior or temperament, such as trainability, 34 play signals, 35 emotional arousal, 36 and acute stress. 37 A survey of 565 dog owners revealed that most participants overestimated the cognitive capabilities of dogs, 38 reflecting how widespread unrealistic expectations of companion animals can be. Such misunderstandings, in the absence of psychological evidence, such as believing certain dog behaviors to be indicative of the animal’s guilt, may be responsible for instances of conflict in dog–human relationships and contribute to relationship breakdowns. 39 These studies appear to be indicative of a general lack of understanding of dog behavior among dog owners and handlers that, if rectified, could improve dog handling, or dogmanship, on a broader scale.

Owner factors affecting dog–human relationships

The operant conditioning quadrant that a dog handler tends to use when training a dog can influence the dog’s affective state, relative arousal, and ultimately, its behavioral output. 40 Generally, producing a positive affective state and moderate arousal in a dog maximizes the probability of that dog demonstrating the desired behavior. 40 In a broader sense, human behavior can likewise influence dog behavior by changing emotional valence and arousal. In the literature, human behaviors that likely contribute to a more positive affective state and consequently more positive expectations in dogs are often those that provide the dog with resources of emotional value, such as affiliation, 22 human attention, 41 and safety. 17 However, the influence of human attachment on dog behavior remains ambiguous. An owner with an avoidant attachment to their dog is reported to have more negative expectations regarding the behavior of their dog. 42

As owner attitudes have been connected to dog behavior and stress, 15 insecure human–dog relationships may be related to poor stress coping in dogs, thereby compromising welfare and contributing to relinquishment. Aligning with this, owners relinquishing their dogs at animal shelters tend to score lower on companion animal attachment compared with existing dog owners. 43 Additionally, owners who are predisposed to view their interactions with their dog as negative may be more likely to fall victim to such miscommunication and then consider relinquishment.

A study investigating the influence of certain owner factors on the dog–human relationship found a significant negative correlation between owners using the dog for ‘company only’ and emotional closeness. 44 The authors defined ‘company only’ as non-participation in herding, hunting, agility, dog shows, or working dog training. Time spent as a dyad may have a critical influence on this observation, as the activities cited by Meyer and Forkman 44 would arguably require more owner engagement with the dog, an attribute that has been reported as critical in the dog–human relationship. 11 , 45 Additionally, humans using their dogs for company alone may arguably have a dominionistic viewpoint of their dogs and hence may be more likely to experience relationship dysfunction than those who are more willing to engage in activities with their animal.

Investigating the effect of human personality on dog–human relationships is of particular relevance when conceptualizing dogmanship as it holds promise of identifying specific characteristics of individuals who are outstanding with their dogs. More specifically, current research suggests the Big Five personality dimension of neuroticism may provide some preliminary indication of the dogmanship of an individual dog owner. High neuroticism scores in dog owners have been associated with poor canine performance in operational tasks, 15 , 46 handlers’ use of excessive signaling during training, 47 and delayed responses to owner commands. 47 Taken together, these results suggest that high neuroticism in dog owners contributes to poor dyadic functionality and that individuals with good dogmanship are likely to score low on this trait. Nevertheless, owners with high neuroticism have been observed to be more socially attractive to their dogs, 48 with these dyads being rated as being more friendly than other dyads by experimental observers 46 and having lower salivary cortisol concentrations in dogs. 15 Additionally, owners in these dyads were more likely to consider their dogs as social supporters or partners. 15 These observations suggest that quality of life for both members of the dog–human dyad does not necessarily relate to performance in practical tasks. Future analyses should focus on examining various dog–human interactions with owners of different personality types and dog training experience levels, to clarify whether high neuroticism correlates with canine welfare and the implications this has for dog training.

Accounting for dog and human personalities when matching dogs with humans has potential to reduce behavioral conflict in the dog–human dyad by preventing mismatches. Significant correlations have been observed between the personality facets of openness and agreeableness and owner satisfaction with the dog–human relationship. 49 Similarly, Curb et al 50 reported that owner satisfaction correlated with dog-and-owner matching on certain behavioral traits, such as having an active lifestyle and creativity, which correlate with extraversion 51 and openness, 52 respectively. To further investigate dog–owner personality matching, future studies should use validated personality dimensions in their assessment, accompanied by direct behavioral observations of dog personality to prevent owner bias.

Dog perceptions of the dog–human relationship

To effectively assess dog–human relationships, canine factors must be considered. It has been hypothesized that dogs have been selected for increased deference to humans and that the dog–human relationship has a defined social hierarchy. 12 , 53 Although intraspecific dominance relationships have been observed in dogs, evidence suggests that dogs do not generally view humans as surrogate dogs; thus, social dominance may not apply in the dog–human dyad. 54 Despite engaging in interactions with other dogs, intraspecific play does not suppress the motivation for dogs to interact with owners, 55 suggesting each interaction fulfils a different role. Furthermore, unlike the presence of a familiar dog, the presence of a familiar human has been shown to reduce plasma cortisol concentrations in dogs in a novel environment. 56 As such, it is likely dog–dog and dog–human interactions are motivationally as well as functionally distinct, and thus, it is unlikely that dog–human interactions operate as part of a dominance hierarchy. It may be that, rather than deference to humans, reduced fear of humans may have had a selection advantage, with these animals being more likely to scavenge from humans.

There are several hypotheses regarding the domestication of the dog and the particular behavioral traits that had a selection advantage. It has been argued that dogs have been selected for their ability to perceive human signals and cooperate with humans. 10 Dogs have been shown to outperform wolves in establishing eye contact with humans and adapting their behavior to human attitudes. 57 , 58 However, given that socialized wolves do seem to interact with their human raisers as social partners, this cooperation may be more due to environment and ontogenic events than human-directed selection. 9 Additionally, wolves can outperform dogs in social-learning tasks with a conspecific demonstrator. 59 This suggests that wolves may be more cooperative with conspecifics than dogs. Consequently, it has been suggested that dog–human cooperation has evolved on the foundation of wolf–wolf cooperation, and during the domestication process, dogs have become less cooperative with each other. 12 This canine cooperation theory aligns with current research. However, given that existing dog–wolf comparisons compare companion dogs to wolves with limited socialization 7 or wolves that have been clicker-trained, 9 there is a need for more balanced comparisons. 60 Future studies should incorporate bigger, more diverse sample sizes of dogs and wolves to assess whether these variations exist between breeds and entire versus desexed animals. Moreover, the modern wolf is genetically distinct from the ancestor of the modern dog. 61 As such, given that modern wolves may not resemble their ancient counterparts, using dog–wolf comparisons to investigate the domestication of the dog may be of limited relevance.

There are early reports that social learning in the form of Do As I Do (DAID) training can be as successful as shaping and clicker-training methods in the training of simple commands and superior to them in the training of complex or sequential commands. 62 These results highlight that imitation can occur in dog–human dyads. However, it is important to note that the authors did not measure the behavior of the human; thus, it is possible that demonstrators may have inadvertently reinforced certain actions. That said, the protocol did involve control conditions, such as the ‘do it’ command being given by an individual who was unfamiliar with the demonstration, thus preventing a Clever Hans effect. However, to the authors’ knowledge, there is no documented evidence of imitation occurring naturally in dog–human relationships; thus, its relevance is questionable. Despite this, the ability of dogs to demonstrate social referencing, adapting their behavior according to human emotional signals, 57 , 63 further reinforces the relevance of social learning in the dog–human relationship. Therefore, it is reasonable to postulate that dogs view humans as peers who often provide salient information about the surrounding environment but are distinct from conspecifics.

In addition to using humans as a social reference point, dogs have been shown to develop attachment bonds with humans. 14 , 16 This relationship allows them to interact securely with their environment in the presence of the owner 18 and show less distress in response to threatening events. 17 Interestingly, the secure base effect seems to operate regardless of whether the owner is encouraging or passive. 18 This suggests that social referencing does not always operate in the dog–human dyad. Indeed, dogs seem to struggle to distinguish between fearful and neutral emotional messages about certain objects and to respond appropriately to emotional messages given by a stranger. 63 As such, relational factors and attachment dimensions probably influence the degree of social referencing between dogs and owners.

The learning history of a dog may also be relevant to the attachment relationships it forms and its social referencing capabilities. For example, trained water rescue dogs have more difficulty than companion dogs in responding to the emotional messages of a stranger. 64 It remains unclear whether these results reflect habituation to strangers giving emotional cues in their training or the dogs’ strong attachment to their handlers. Further studies of dogs in various working and companion contexts may disambiguate the relevance of attachment and learning history in the ability of dogs to respond to human social cues.

Potential interactions between human and dog attachment patterns require clarification. Rehn et al 20 found no evidence of an interaction between perceived emotional closeness, assessed via the Monash Dog Owner Relationship Scale (MDORS), and dog attachment behaviors, assessed using the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP). In contrast, Siniscalchi et al 19 reported a relationship in which owner attachment (confident vs unconfident) was measured using the 9 Attachment Profile (9AP) and dog attachment was measured using the SSP. These authors reported that dogs of confident owners displayed more proximity-seeking behaviors and were more likely to interact with the owner when a stranger was present compared with dogs of owners lacking in confidence. Further studies using both the 9AP and the MDORS, in conjunction with standardized behavioral observations of both dogs and handlers, may assist in clarifying the existence of such an interaction.

Tools and methods to measure the dog–human relationship

Identification of high-risk pairings of dogs and humans offers a means of preventing dysfunction in the dog–human dyad. Additionally, outstanding dyads can provide models of dogmanship strategies that could then be applied in those dyads that tend to struggle. Therefore, a means of measuring the dog–human relationship has great potential for reducing disharmony. Although scales of this nature have been created, 26 there is no generally accepted tool to measure the dog–human bond. One questionnaire designed to measure the dog–human relationship was not given a name by researchers. 46 Accordingly, for convenience, the authors of the current review will refer to it as the Modified Person–Animal Wellness Scale (MPAWS).

Some dog–human relationship assessment tools tend to focus on the human factors of a dog–human relationship, particularly attachment. One such measure, the Dog Attachment Questionnaire (DAQ), was developed to measure human attachment to their canine companions. 65 Given that human factors generally have more influence on the dog–human bond than canine factors, 44 using measures such as the DAQ seems appropriate. However, such approaches may be overly simplistic, as attachment dimensions alone may fail to capture the influence of specific human behaviors, such as affiliation, and perceptions on the dog–human relationship. Furthermore, as we are defining the human–animal bond (HAB) as a symbiotic relationship, affective benefits to the dog, through attachment or otherwise, should be considered.

There are existing measures of the dog–human bond that consider canine factors. Schneider et al 66 created an internally consistent measure of the HAB that embraced human attachment and its potential to bias dog health ratings. While this measure did consider canine attachment, only one scale within it was devoted to it, while the remaining five related to human perceptions of the relationship. When testing the measure, the authors used a relatively homogenous sample. Hence, the results are not representative of the general population. Therefore, the researchers may have failed to capture some aspects of dog–human relationships. Moreover, given that the HAB has yet to be used in other studies, its overall applicability to examine dog–human relationships in general remains unclear.

The MPAWS 42 was developed from the Person–Animal Wellness Scale (PAWS) 67 and the Questionnaire for Anthropomorphic Attitudes. 68 This questionnaire features items concerning dog attachment and the owner–dog relationship, with four separate subscales for each of these sections. Additionally, the MPAWS asks owners about their attitude toward their dog. Significant associations have been observed within owner opinion items as well as the shared activities subscale. For example, neurotic owners reported less engagement in shared activities with their dogs. 46 Moreover, the MPAWS has been used in subsequent studies, identifying significant correlations between stress hormone concentrations 15 and proximity-seeking behaviors. 48 However, aside from a principal component analysis, the authors reported no further statistical validation. Furthermore, the sample sizes for these studies were relatively small (n=22), such that any assumptions or generalizations from their results must be made with caution as they may not be applicable to dog–human dyads in general. Furthermore, many subscales had no significant relationship with dog or owner factors. Therefore, further refinement and validation of this questionnaire are required.

The MDORS has had widespread use. 20 , 44 , 69 – 71 It was also tested using an extensive, heterogeneous sample of participants, which indicates that the initial population was probably representative of dog owners in general. Unlike tools such as the MPAWS, this scale has been tested for both validity and reliability. 69 Despite this, it has been suggested that the MDORS focuses too much on the human member of the dog–human dyad and, thus, might overlook several aspects of the relationship that are pertinent to the emotional wellness of the dog. 20 A recent study 44 reported that variance in MDORS scores correlated with only one dog personality subscale, as determined by Dog Mentality Assessment (DMA) results. Taken together, these results suggest that, while the MDORS is currently the most reliable measure of the dog–human relationship, it has potential to exclude canine factors. To address this, future studies should combine the MDORS with behavioral test batteries to categorize dog temperament effectively and establish its contribution to the dog–human bond.

Thus far, all tools discussed require owner reports of their behavior, the behavior of their dog, and their attitudes towards the relationship. While owner reports are arguably effective, interobserver reliability has been shown to vary depending on the particular trait being rated. 72 , 73 Additionally, physical traits such as ear shape and coat color have been reported to affect ratings of dog behavior and personality. 74 Gosling discusses several causes for interobserver variation, such as familiarity with the animal and exposure to the species in question. 75 Furthermore, as previously discussed, there is ample evidence that owners may misinterpret their dog’s behavior and cognitive capacity. Taken together, this suggests that owner reports alone may not be a sufficient measure of dog–human relationships. Future studies should seek to combine owner reports with test batteries designed to measure dog–human cooperation and interaction styles. At the very least, studies using questionnaires should collect ratings from more than one individual and examine interobserver agreement.

There are several tools that assess the dog–human relationship from the perspective of dog attachment. The application of Ainsworth’s Strange Situation Test (SST), a measure originally designed to assess attachment of human infants to their mothers, has revealed several distinct attachment patterns in dogs. 16 This procedure has been used extensively to gauge canine attachment to humans, 76 , 77 with some authors proposing, by extrapolation, that the dog’s behavior during the SST is a reflection of the bond it has developed with its owner. 19 Interestingly, human behavior during the SST has been shown to influence dog behavior and cortisol concentrations. 78 This indicates that owner behavior may bias dog behavioral observations during the SST to the extent that results may not reflect dog attachment alone. Future studies could examine how various owners differ in their behavior during the SST, such as during reunions, and how these variations affect dog behavior. Potentially, the SST may be more useful in assessing the dog–human bond than originally anticipated, if both dog and human behaviors are coded and analyzed simultaneously.

Biochemical and physiological effects of dog–human interactions

Dyadic interactions between humans and dogs can yield both mutual and individual positive effects. The dog–human relationship can be a more influential determinant of canine salivary cortisol concentrations than environmental stressors, such as a threatening stranger. 15 This is likely mediated by the safe haven effect or possible social referencing if the owner is not fearful of the environment. Likewise, human interaction has been demonstrated to reduce plasma cortisol concentrations in shelter dogs, 79 suggesting human–dog interactions may help dogs to cope with stress, almost regardless of relationship quality. Alternatively, the stressful shelter environment may have facilitated the rapid formation of an attachment bond. The specific nature of the interaction also seems to be relevant. Border guard dogs that had affiliative interactions with their handlers showed a more pronounced reduction in cortisol concentrations than police dogs subjected to authoritative interactions. 22 Owners kissing their dogs reportedly have higher oxytocin concentrations, as do their dogs, than owners who do not. 71 Oxytocin is believed to have a role in bond formation, 80 so frequent affiliative interactions between dogs and humans probably strengthen bond formation. This may provide a physiological explanation of why the amount of time that dogs and owners spend together is often reported to have a critical influence on both dogmanship 11 and functional dog–human relationships. 46 These results emphasize the importance of affiliative interactions in the dog–human dyad, and their capacity to reduce stress and strengthen bond formation in both dogs and owners.

Conclusion and future directions

This review highlights growing evidence that human factors, including personality and attitudes, influence the dog–human relationship. In particular, both positive attitudes and affiliative behavior seem to contribute to a strong dog–human bond, as is apparently confirmed by hormonal changes that emerge in both dyad members. This illustrates the benefits that can ensue from successful dog–human relationships and should inspire the cultivation of such relationships. In contrast, negative attitudes, insecure attachment, and misunderstanding of dog behavior have the potential to disrupt relationships and even lead to dog relinquishment. Future studies should consider the influence of both owner attitudes and behavior on canine physiology and affective states. Such investigations may reveal a potential causal relationship between attitudes and behavior. Interestingly, although the human personality dimension of neuroticism may relate to poor dyadic functionality, it may not compromise the quality of the relationship. Assessing the personality of working dog handlers in a standardized setting may clarify whether neuroticism contributes to a given dyad’s struggle with practical tasks.

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of social and associative learning in the dog–human dyad. Indeed, given the ease with which dogs learn complex commands and behavioral sequences, training methods that exploit social learning, such as DAID, as a complement to shaping techniques may provide a means of further capitalizing on the dogmanship of handlers.

Importantly, the dog–human relationship and attachment relationships held by both humans and dogs may not be complementary. The MDORS is currently the most robust measure of the dog–human relationship, addressing primarily the human perceptions of the relationship. Future studies investigating the influence of dog temperament, measured using an internally consistent, validated scale, on the dog–human relationship may reveal how the MDORS should be refined to capture more information on canine members of the dyad. Moreover, to investigate the relationship between the dog–human bond and attachment, a measure of canine attachment, such as the SST, should also be included. The ability to produce successful dog–human dyads through the identification of factors contributing to the HAB promises to enhance the welfare of both species in this unique and ancient dyad.

None of the authors of this paper has a financial or personal relationship with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence or bias the content of the paper.

- 1. Thalmann O, Shapiro B, Cui P, et al. Complete mitochondrial genomes of ancient canids suggest a European origin of domestic dogs. Science. 2013;342(6160):871–874. doi: 10.1126/science.1243650. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Landsberg GM, Hunthausen WL, Ackerman LJ. Handbook of Behavior Problems of the Dog and Cat. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2003. [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Bradshaw JW, Blackwell EJ, Casey RA. Dominance in domestic dogs-useful construct or bad habit? J Vet Behav. 2009;4(3):135–144. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Kubinyi E, Pongrácz P, Miklósi A. Dog as a model for studying conspecific and heterospecific social learning. J Vet Behav. 2009;4(1):31–41. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Elgier AM, Jakovcevic A, Mustaca AE, Bentosela M. Pointing following in dogs: are simple or complex cognitive mechanisms involved? Anim Cogn. 2012;15(6):1111–1119. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Miklósi A, Topál J, Csányi V. Comparative social cognition: what can dogs teach us? Anim Behav. 2004;67(6):995–1004. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Gácsi M, Gyoöri B, Virányi Z, et al. Explaining dog wolf differences in utilizing human pointing gestures: selection for synergistic shifts in the development of some social skills. PLoS One. 2009;4(8):e6584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006584. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Kirchhofer KC, Zimmermann F, Kaminski J, Tomasello M. Dogs (Canis familiaris), but not chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), understand imperative pointing. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030913. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Udell MR, Dorey NR, Wynne CD. Wolves outperform dogs in following human social cues. Anim Behav. 2008;76(6):1767–1773. [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Reid PJ. Adapting to the human world: dogs’ responsiveness to our social cues. Behav Processes. 2009;80(3):325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2008.11.002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Lefebvre D, Diederich C, Delcourt M, Giffroy JM. The quality of the relation between handler and military dogs influences efficiency and welfare of dogs. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2007;104(1–2):49–60. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Kaminski J, Marshall-Pescini S. The Social Dog: Behavior and Cognition. Burlington, VT: Elsevier Science; 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Bowlby J. The nature of the childs tie to his mother. Int J Psychoanal. 1958;39(5):350–373. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Serpell JA. Evidence for an association between pet behavior and owner attachment levels. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1996;47(1–2):49–60. [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Schoeberl I, Wedl M, Bauer B, Day J, Moestl E, Kotrschal K. Effects of owner-dog relationship and owner personality on cortisol modulation in human-dog dyads. Anthrozoos. 2012;25(2):199–214. [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Topál J, Miklósi A, Csányi V, Dóka A. Attachment behavior in dogs (Canis familiaris): a new application of Ainsworth’s (1969) Strange Situation Test. J Comp Psychol. 1998;112(3):219–229. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.112.3.219. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Gácsi M, Maros K, Sernkvist S, Faragó T, Miklósi A. Human analogue safe haven effect of the owner: behavioural and heart rate response to stressful social stimuli in dogs. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058475. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Horn L, Huber L, Range F. The importance of the secure base effect for domestic dogs – evidence from a manipulative problem-solving task. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e65296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065296. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Siniscalchi M, Stipo C, Quaranta A. “Like owner, like dog”: correlation between the owner’s attachment profile and the owner-dog bond. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e78455. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078455. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Rehn T, Lindholm U, Keeling L, Forkman B. I like my dog, does my dog like me? Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2014;150:65–73. [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Deldalle S, Gaunet F. Effects of 2 training methods on stress-related behaviors of the dog (Canis familiaris) and on the dog-owner relationship. J Vet Behav. 2014;9(2):58–65. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Horvath Z, Doka A, Miklosi A. Affiliative and disciplinary behavior of human handlers during play with their dog affects cortisol concentrations in opposite directions. Horm Behav. 2008;54(1):107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.02.002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. McGreevy PD, Boakes RA. Carrots and Sticks: Principles of Animal Training. Sydney, Australia: Darlington Press; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Barker SB, Wolen AR. The benefits of human-companion animal interaction: a review. J Vet Med Educ. 2008;35(4):487–495. doi: 10.3138/jvme.35.4.487. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Schneider AA, Rosenberg J, Baker M, Melia N, Granger B, Biringen Z. Becoming relationally effective: high-risk boys in animal-assisted therapy. Hum Anim Interact Bull. 2014;2(1):1–18. [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Wilson CC, Netting FE. The status of instrument development in the human-animal interaction field. Anthrozoos. 2012;25(Suppl 1):S11–S55. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Anderson DC. Assessing the Human-Animal Bond: A Compendium of Actual Measures. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Guy NC, Luescher UA, Dohoo SE, et al. A case series of biting dogs: characteristics of the dogs, their behaviour, and their victims. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2001;74(1):43–57. [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Patronek GJ, Glickman LT, Beck AM, McCabe GP, Ecker C. Risk factors for relinquishment of dogs to an animal shelter. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1996;209(3):572–581. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Miller R, Howell GV. Regulating consumption with bite: building a contemporary framework for urban dog management. J Bus Res. 2008;61(5):525–531. [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Ellingsen K, Zanella AJ, Bjerkås E, Indrebø A. The relationship between empathy, perception of pain and attitudes toward pets among Norwegian dog owners. Anthrozoos. 2010;23(3):231–243. [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Blouin DD. Are dogs children, companions, or just animals? Understanding variations in people’s orientations toward animals. Anthrozoos. 2013;26(2):279–294. [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Savalois N, Lescureux N, Brunois F. Teaching the dog and learning from the dog: interactivity in herding dog training and use. Anthrozoos. 2013;26(1):77–91. [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Mirkó E, Dóka A, Miklósi A. Association between subjective rating and behaviour coding and the role of experience in making video assessments on the personality of the domestic dog (Canis familiaris) Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2013;149(1–4):45–54. [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Tami G, Gallagher A. Description of the behaviour of domestic dog (Canis familiaris) by experienced and inexperienced people. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2009;120(3–4):159–169. [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Kerswell KJ, Butler KL, Bennett P, Hemsworth PH. The relationships between morphological features and social signalling behaviours in juvenile dogs: the effect of early experience with dogs of different morphotypes. Behav Processes. 2010;85(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2010.05.006. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Mariti C, Gazzano A, Moore JL, Baragli P, Chelli L, Sighieri C. Perception of dogs’ stress by their owners. J Vet Behav. 2012;7(4):213–219. [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Howell TJ, Toukhsati S, Conduit R, Bennett P. The Perceptions of Dog Intelligence and Cognitive Skills (PoDIaCS) Survey. J Vet Behav. 2013;8(6):418–424. [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Horowitz A. Disambiguating the “guilty look”: Salient prompts to a familiar dog behaviour. Behav Processes. 2009;81(3):447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2009.03.014. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Starling MJ, Branson NJ, Cody D, McGreevy PD. Conceptualising the impact of arousal and affective state on training outcomes of operant conditioning. Animals. 2013;3(2):300–317. doi: 10.3390/ani3020300. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Schwab C, Huber L. Obey or not obey? Dogs (Canis familiaris) behave differently in response to attentional states of their owners. J Comp Psychol. 2006;120(3):169–175. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.120.3.169. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Zilcha-Mano S, Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. An attachment perspective on human-pet relationships: conceptualization and assessment of pet attachment orientations. J Res Pers. 2011;45(4):345–357. [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Kwan JY, Bain MJ. Owner attachment and problem behaviors related to relinquishment and training techniques of dogs. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2013;16(2):168–183. doi: 10.1080/10888705.2013.768923. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Meyer I, Forkman B. Dog and owner characteristics affecting the dog-owner relationship. J Vet Behav. 2014;9(4):143–150. [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Arhant C, Bubna-Littitz H, Bartels A, Futschik A, Troxler J. Behaviour of smaller and larger dogs: effects of training methods, inconsistency of owner behaviour and level of engagement in activities with the dog. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2010;123(3–4):131–142. [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Kotrschal K, Schöberl I, Bauer B, Thibeaut AM, Wedl M. Dyadic relationships and operational performance of male and female owners and their male dogs. Behav Processes. 2009;81(3):383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2009.04.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Kis A, Turcsán B, Gácsi M. The effect of the owner’s personality on the behaviour of owner-dog dyads. Interact Stud. 2012;13(3):373–385. [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Wedl M, Schöberl I, Bauer B, Day J, Kotrschal K. Relational factors affecting dog social attraction to human partners. Interact Stud. 2010;11(3):482–503. [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Cavanaugh LA, Leonard HA, Scammon DL. A tail of two personalities: how canine companions shape relationships and well-being. J Bus Res. 2008;61(5):469–479. [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. Curb LA, Abramson CI, Grice JW, Kennison SM. The relationship between personality match and pet satisfaction among dog owners. Anthrozoos. 2013;26(3):395–404. [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. de Bruijn GJ, de Groot R, van den Putte B, Rhodes R. Conscientiousness, extraversion, and action control: comparing moderate and vigorous physical activity. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2009;31(6):724–742. doi: 10.1123/jsep.31.6.724. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Sung SY, Choi JN. Do Big Five personality factors affect individual creativity? The moderating role of extrinsic motivation. Soc Behav Pers. 2009;37(7):941–956. [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Schilder MB, Vinke CM, van der Borg JA. Dominance in domestic dogs revisited: useful habit and useful construct? J Vet Behav. 2014;9(4):184–191. [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Ákos Z, Beck R, Nagy M, Vicsek T, Kubinyi E. Leadership and path characteristics during walks are linked to dominance order and individual traits in dogs. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10(1):e1003446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003446. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Rooney NJ, Bradshaw JW, Robinson IH. A comparison of dog-dog and dog-human play behaviour. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2000;66(3):235–248. [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Tuber DS, Sanders S, Hennessy MB, Miller JA. Behavioral and glucocorticoid responses of adult domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) to companionship and social separation. J Compar Psychol. 1996;110(1):103–108. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.110.1.103. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Gácsi M, Vas J, Topál J, Miklósi A. Wolves do not join the dance: sophisticated aggression control by adjusting to human social signals in dogs. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2013;145(3–4):109–122. [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Virányi Z1, Gácsi M, Kubinyi E, et al. Comprehension of human pointing gestures in young human-reared wolves (Canis lupus) and dogs (Canis familiaris) Anim Cogn. 2008;11(3):373–387. doi: 10.1007/s10071-007-0127-y. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Range F, Virányi Z. Wolves are better imitators of conspecifics than dogs. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086559. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 60. Range F, Virányi Z. Social learning from humans or conspecifics: differences and similarities between wolves and dogs. Front Psychol. 2013;4:868. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00868. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 61. Freedman AH, Gronau I, Schweizer RM, et al. Genome sequencing highlights the dynamic early history of dogs. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(1):e1004016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004016. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 62. Fugazza C, Miklósi A. Should old dog trainers learn new tricks? The efficiency of the Do as I do method and shaping/clicker training method to train dogs. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2014;153:53–61. [ Google Scholar ]

- 63. Merola I, Prato-Previde E, Lazzaroni M, Marshall-Pescini S. Dogs’ comprehension of referential emotional expressions: familiar people and familiar emotions are easier. Anim Cogn. 2014;17(2):373–385. doi: 10.1007/s10071-013-0668-1. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 64. Merola I, Marshall-Pescini S, D’Aniello B, Prato-Previde E. Social referencing: water rescue trained dogs are less affected than pet dogs by the stranger’s message. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2013;147(1–2):132–138. [ Google Scholar ]

- 65. Archer J, Ireland JL. The development and factor structure of a questionnaire measure of the strength of attachment to pet dogs. Anthrozoos. 2011;24(3):249–261. [ Google Scholar ]

- 66. Schneider TR, Lyons JB, Tetrick MA, Accortt EE. Multidimensional quality of life and human-animal bond measures for companion dogs. J Vet Behav. 2010;5(6):287–301. [ Google Scholar ]

- 67. Johannson EE. Human-Animal Bonding: An Investigation of Attributes [doctoral thesis] Edmonton, AB: University of Alberta; 1999. [ Google Scholar ]

- 68. Topál J, Miklósi A, Csányi V. Dog-human relationship affects problem solving behavior in the dog. Anthrozoos. 1997;10(4):214–224. [ Google Scholar ]

- 69. Dwyer F, Bennett PC, Coleman GJ. Development of the Monash Dog Owner Relationship Scale (MDORS) Anthrozoos. 2006;19(3):243–256. [ Google Scholar ]

- 70. Bennett PC, Cooper N, Rohlf VI, Mornement K. Factors influencing owner satisfaction with companion-dog-training facilities. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2007;10(3):217–241. doi: 10.1080/10888700701353626. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 71. Handlin L, Nilsson A, Ejdebäck M, Hydbring-Sandberg E, Uvnäs-Moberg K. Associations between the psychological characteristics of the human-dog relationship and oxytocin and cortisol levels. Anthrozoos. 2012;25(2):215–228. [ Google Scholar ]

- 72. Ley JM, Bennett PC, Coleman GJ. A refinement and validation of the Monash Canine Personality Questionnaire (MCPQ) Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2009;116(2–4):220–227. [ Google Scholar ]

- 73. Rooney NJ, Gaines SA, Bradshaw JW, Penman S. Validation of a method for assessing the ability of trainee specialist search dogs. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2007;103(1–2):90–104. [ Google Scholar ]

- 74. Fratkin JL, Baker SC. The role of coat color and ear shape on the perception of personality in dogs. Anthrozoos. 2013;26(1):125–133. [ Google Scholar ]

- 75. Gosling SD. From mice to men: what can we learn about personality from animal research? Psychol Bull. 2001;127(1):45–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.45. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 76. Prato-Previde E, Custance DM, Spiezio C, Sabatini F. Is the dog-human relationship an attachment bond? An observational study using Ainsworth’s strange situation. Behaviour. 2003;140:225–254. [ Google Scholar ]

- 77. Palmer R, Custance D. A counterbalanced version of Ainsworth’s Strange Situation Procedure reveals secure-base effects in dog-human relationships. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2008;109(2–4):306–319. [ Google Scholar ]

- 78. Rehn T, Handlin L, Uvnäs-Moberg K, Keeling LJ. Dogs’ endocrine and behavioural responses at reunion are affected by how the human initiates contact. Physiol Behav. 2014;124:45–53. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 79. Shiverdecker MD, Schiml PA, Hennessy MB. Human interaction moderates plasma cortisol and behavioral responses of dogs to shelter housing. Physiol Behav. 2013;109:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.12.002. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 80. Carter CS, DeVries AC, Taymans SE, Roberts RL, Williams JR, Getz LL. Peptides, Steroids, and Pair Bonding. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;807:260–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb51925.x. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (208.2 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Dog — Importance of Dogs

Importance of Dogs

- Categories: Dog

About this sample

Words: 659 |

Published: Jun 13, 2024

Words: 659 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Companionship and emotional support, health benefits, societal contributions.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1039 words

2 pages / 745 words

2 pages / 829 words

3 pages / 1413 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Dog

Feed your dog a high quality dog food. Read the label of a prospective food. The first couple ingredients should be some kind of meat, not meat by-product or a grain. This will help you know that the food is high in good [...]

Personal statement essays are an opportunity for individuals to express their unique experiences and perspectives. In this essay, I will be discussing my personal history with dogs and the impact my current dog has had on my [...]

Suzan-Lori Parks' Pulitzer Prize-winning play "Topdog/Underdog" is a profound exploration of the complexities of identity, power, and human relationships. Through the lives of two African American brothers, Lincoln and Booth, [...]

Mariano Azuela's novel, The Underdogs (Los de Abajo), offers a vivid portrayal of the Mexican Revolution, capturing the essence of conflict, social upheaval, and the inherent struggles of the marginalized. Published in [...]

One difference between adopting and buying a dog is the type of dog in which someone is able to choose from. When adopting a dog, the dog someone will most likely choose will be a mutt. Of course being a mutt does not make the [...]

Lopata, L. (2020). Dogs Have Been Humans' Best Friends for 20,000 Years, According to Artifacts. Mental Floss. Retrieved from https://www.akc.org/dog-breeds/why-dogs-are-mans-best-friend/

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

Dogs supporting human health and well-being: a biopsychosocial approach.

- 1 Department of Psychiatry, Center for Human Animal Interaction, School of Medicine, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, United States

- 2 Human-Animal Bond in Colorado, School of Social Work, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, United States

- 3 Department of Education, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, CA, United States

- 4 Division of Social Sciences and Natural Sciences, Seaver College, Pepperdine University, Malibu, CA, United States

Humans have long realized that dogs can be helpful, in a number of ways, to achieving important goals. This is evident from our earliest interactions involving the shared goal of avoiding predators and acquiring food, to our more recent inclusion of dogs in a variety of contexts including therapeutic and educational settings. This paper utilizes a longstanding theoretical framework- the biopsychosocial model- to contextualize the existing research on a broad spectrum of settings and populations in which dogs have been included as an adjunct or complementary therapy to improve some aspect of human health and well-being. A wide variety of evidence is considered within key topical areas including cognition, learning disorders, neurotypical and neurodiverse populations, mental and physical health, and disabilities. A dynamic version of the biopsychosocial model is used to organize and discuss the findings, to consider how possible mechanisms of action may impact overall human health and well-being, and to frame and guide future research questions and investigations.

Introduction – A Historical Perspective on Dog-Human Relationships

The modern relationship between humans and dogs is undoubtedly unique. With a shared evolutionary history spanning tens of thousands of years ( 1 ), dogs have filled a unique niche in our lives as man's best friend. Through the processes of domestication and natural selection, dogs have become adept at socializing with humans. For example, research suggests dogs are sensitive to our emotional states ( 2 ) as well as our social gestures ( 3 ), and they also can communicate with us using complex cues such as gaze alternation ( 4 ). In addition, dogs can form complex attachment relationships with humans that mirror that of infant-caregiver relationships ( 5 ).

In today's society, dog companionship is widely prevalent worldwide. In the United States, 63 million households have a pet dog, a majority of which consider their dog a member of their family ( 6 ). In addition to living in our homes, dogs have also become increasingly widespread in applications to assist individuals with disabilities as assistance dogs. During and following World War I, formal training of dogs as assistance animals began particularly for individuals with visual impairments in Germany and the United States ( 7 ). Following World War II, formal training for other roles, such as mobility and hearing assistance, started to increase in prevalence. Over the decades, the roles of assistance dogs have expanded to assist numerous disabilities and conditions including medical conditions such as epilepsy and diabetes and mental health disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). At the same time, society has also seen increasing applications of dogs incorporated into working roles including detection, hunting, herding, and protection ( 8 , 9 ).

In addition to these working roles, dogs have also been instrumental in supporting humans in other therapeutic ways. In the early 1960s, animal-assisted interventions (AAI) began to evolve with the pioneering work of Boris Levinson, Elizabeth O'Leary Corson, and Samuel Corson. Levinson, a child psychologist practicing since the 1950s, noticed a child who was nonverbal and withdrawn during therapy began interacting with his dog, Jingles, in an unplanned interaction. This experience caused Levinson to begin his pioneering work in creating the foundations for AAI as an adjunct to treatment ( 10 ). In the 1970s, Samuel Corson and Elizabeth O'Leary Corson were some of the first researchers to empirically study canine-assisted interventions. Like Levinson, they inadvertently discovered that some of their patients with psychiatric disorders were interested in the dogs and that their patients with psychiatric disorders communicated more easily with each other and the staff when in the company of the dogs ( 11 , 12 ). Over the following decades, therapy dogs have been increasingly found to provide support for individuals with diverse needs in a wide array of settings ( 13 ).

Theoretical Framework for Dog Interaction Benefits

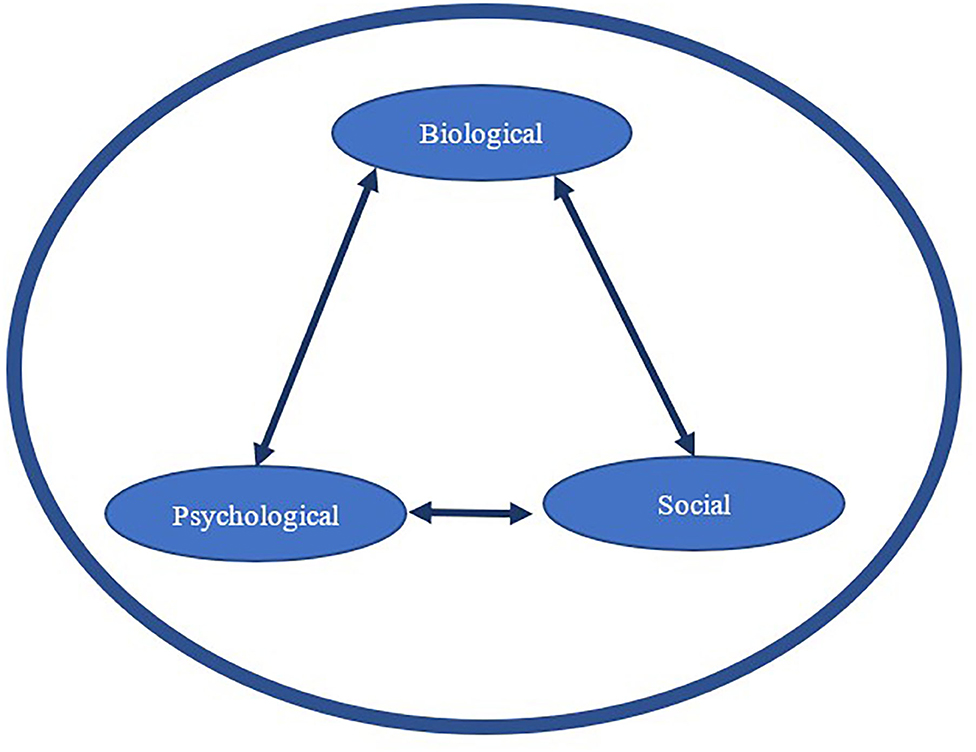

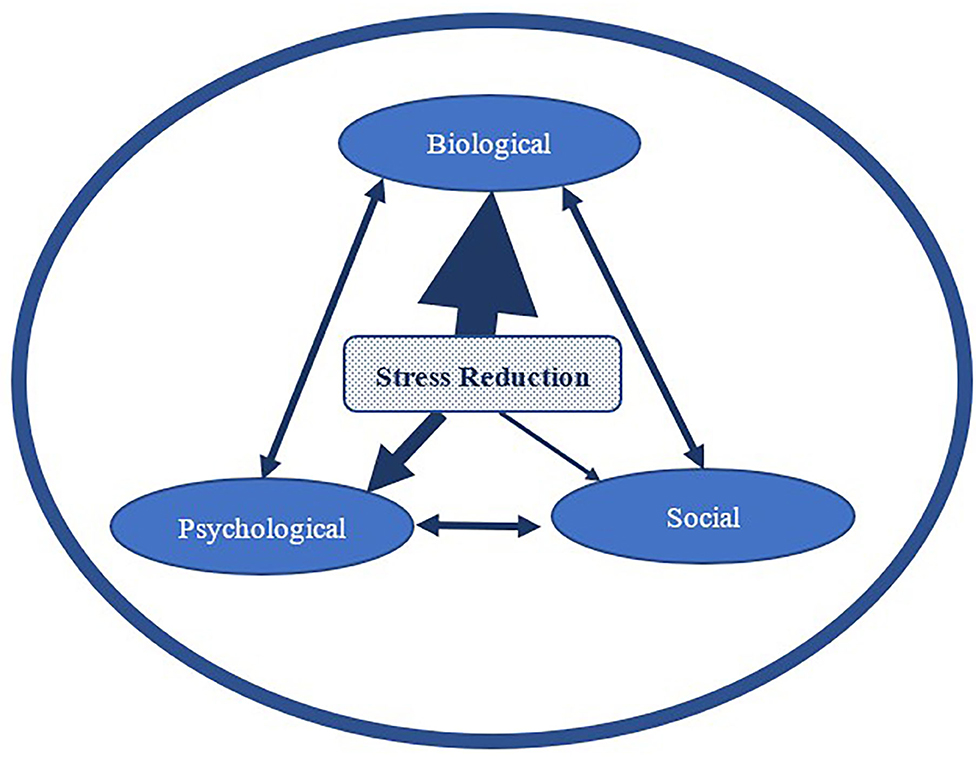

For over 40 years, the biopsychosocial model ( 14 ) has been widely used to conceptualize how biological, psychological, and social influences combine to determine human health and well-being. Biological influences refer to physiological changes such as blood pressure, cortisol, and heart rate, among others; psychological influences include personality, mood, and emotions, among others; and social influences refer to cultural, socio-economic, social relationships with others, family dynamics, and related matters. Figure 1 presents a graphical illustration of the relationship among these three influences in determining overall health and well-being. Although the model has dominated research and theory in health psychology for decades, more recently, it was re-envisioned as a more dynamic system ( 15 ) that construes human health as the result of the reciprocal influences of biological, psychological and social factors that unfold over personal and historical time. For example, if a person breaks his/her arm, there will be a biological impact in that immune and muscle systems respond and compensate. Social, or interpersonal, changes may occur when support or assistance is offered by others. Psychological changes will occur as a result of adjusting to and coping with the injury. Thus, the injury represents a dynamic influence initiated at one point in time and extending forward in time with diminishing impact as healing occurs.

Figure 1 . A biopsychosocial perspective of how biological, psychological, and social influences may impact one another (solid lined arrows) and influence human health and well-being (represented here by the large thick circular shape).

This dynamic biopsychosocial approach to understanding health and well-being is appealing to the field of human-animal interaction (HAI) because of the dynamic nature of the relationship between humans and animals. For example, a person may acquire many dogs over his/her lifetime, perhaps from childhood to old age, and each of those dogs may sequentially develop from puppyhood to old age in that time. Behaviorally, the way the human and the dog interact is likely to be different across the lifespans of both species. From a biopsychosocial model perspective, the dynamic nature of the human-canine relationship may differentially interact with each of the three influencers (biological, psychological, and social) of human health and well-being over the trajectories of both beings. Notably, these influencers are not fixed, but rather have an interactional effect with each other over time.

While a person's biological, psychological, and social health may affect the relationship between that person and dogs with whom interactions occur, the focus of this manuscript is on the reverse: how owning or interacting with a dog may impact each of the psychological, biological, and social influencers of human health. We will also present relevant research and discuss potential mechanisms by which dogs may, or may not, contribute to human health and well-being according to the biopsychosocial model. Finally, we will emphasize how the biopsychosocial theory can be easily utilized to provide firmer theoretical foundations for future HAI research and applications to therapeutic practice and daily life.

Psychological Influences