An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Lau F, Kuziemsky C, editors. Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet]. Victoria (BC): University of Victoria; 2017 Feb 27.

Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet].

Chapter 9 methods for literature reviews.

Guy Paré and Spyros Kitsiou .

9.1. Introduction

Literature reviews play a critical role in scholarship because science remains, first and foremost, a cumulative endeavour ( vom Brocke et al., 2009 ). As in any academic discipline, rigorous knowledge syntheses are becoming indispensable in keeping up with an exponentially growing eHealth literature, assisting practitioners, academics, and graduate students in finding, evaluating, and synthesizing the contents of many empirical and conceptual papers. Among other methods, literature reviews are essential for: (a) identifying what has been written on a subject or topic; (b) determining the extent to which a specific research area reveals any interpretable trends or patterns; (c) aggregating empirical findings related to a narrow research question to support evidence-based practice; (d) generating new frameworks and theories; and (e) identifying topics or questions requiring more investigation ( Paré, Trudel, Jaana, & Kitsiou, 2015 ).

Literature reviews can take two major forms. The most prevalent one is the “literature review” or “background” section within a journal paper or a chapter in a graduate thesis. This section synthesizes the extant literature and usually identifies the gaps in knowledge that the empirical study addresses ( Sylvester, Tate, & Johnstone, 2013 ). It may also provide a theoretical foundation for the proposed study, substantiate the presence of the research problem, justify the research as one that contributes something new to the cumulated knowledge, or validate the methods and approaches for the proposed study ( Hart, 1998 ; Levy & Ellis, 2006 ).

The second form of literature review, which is the focus of this chapter, constitutes an original and valuable work of research in and of itself ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Rather than providing a base for a researcher’s own work, it creates a solid starting point for all members of the community interested in a particular area or topic ( Mulrow, 1987 ). The so-called “review article” is a journal-length paper which has an overarching purpose to synthesize the literature in a field, without collecting or analyzing any primary data ( Green, Johnson, & Adams, 2006 ).

When appropriately conducted, review articles represent powerful information sources for practitioners looking for state-of-the art evidence to guide their decision-making and work practices ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Further, high-quality reviews become frequently cited pieces of work which researchers seek out as a first clear outline of the literature when undertaking empirical studies ( Cooper, 1988 ; Rowe, 2014 ). Scholars who track and gauge the impact of articles have found that review papers are cited and downloaded more often than any other type of published article ( Cronin, Ryan, & Coughlan, 2008 ; Montori, Wilczynski, Morgan, Haynes, & Hedges, 2003 ; Patsopoulos, Analatos, & Ioannidis, 2005 ). The reason for their popularity may be the fact that reading the review enables one to have an overview, if not a detailed knowledge of the area in question, as well as references to the most useful primary sources ( Cronin et al., 2008 ). Although they are not easy to conduct, the commitment to complete a review article provides a tremendous service to one’s academic community ( Paré et al., 2015 ; Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). Most, if not all, peer-reviewed journals in the fields of medical informatics publish review articles of some type.

The main objectives of this chapter are fourfold: (a) to provide an overview of the major steps and activities involved in conducting a stand-alone literature review; (b) to describe and contrast the different types of review articles that can contribute to the eHealth knowledge base; (c) to illustrate each review type with one or two examples from the eHealth literature; and (d) to provide a series of recommendations for prospective authors of review articles in this domain.

9.2. Overview of the Literature Review Process and Steps

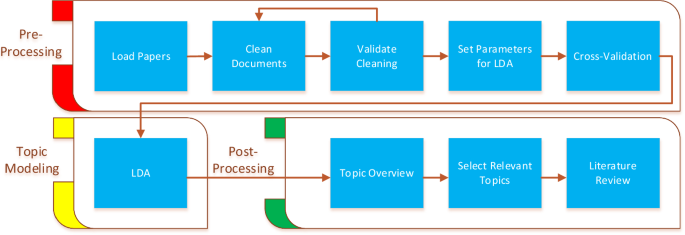

As explained in Templier and Paré (2015) , there are six generic steps involved in conducting a review article:

- formulating the research question(s) and objective(s),

- searching the extant literature,

- screening for inclusion,

- assessing the quality of primary studies,

- extracting data, and

- analyzing data.

Although these steps are presented here in sequential order, one must keep in mind that the review process can be iterative and that many activities can be initiated during the planning stage and later refined during subsequent phases ( Finfgeld-Connett & Johnson, 2013 ; Kitchenham & Charters, 2007 ).

Formulating the research question(s) and objective(s): As a first step, members of the review team must appropriately justify the need for the review itself ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ), identify the review’s main objective(s) ( Okoli & Schabram, 2010 ), and define the concepts or variables at the heart of their synthesis ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ; Webster & Watson, 2002 ). Importantly, they also need to articulate the research question(s) they propose to investigate ( Kitchenham & Charters, 2007 ). In this regard, we concur with Jesson, Matheson, and Lacey (2011) that clearly articulated research questions are key ingredients that guide the entire review methodology; they underscore the type of information that is needed, inform the search for and selection of relevant literature, and guide or orient the subsequent analysis. Searching the extant literature: The next step consists of searching the literature and making decisions about the suitability of material to be considered in the review ( Cooper, 1988 ). There exist three main coverage strategies. First, exhaustive coverage means an effort is made to be as comprehensive as possible in order to ensure that all relevant studies, published and unpublished, are included in the review and, thus, conclusions are based on this all-inclusive knowledge base. The second type of coverage consists of presenting materials that are representative of most other works in a given field or area. Often authors who adopt this strategy will search for relevant articles in a small number of top-tier journals in a field ( Paré et al., 2015 ). In the third strategy, the review team concentrates on prior works that have been central or pivotal to a particular topic. This may include empirical studies or conceptual papers that initiated a line of investigation, changed how problems or questions were framed, introduced new methods or concepts, or engendered important debate ( Cooper, 1988 ). Screening for inclusion: The following step consists of evaluating the applicability of the material identified in the preceding step ( Levy & Ellis, 2006 ; vom Brocke et al., 2009 ). Once a group of potential studies has been identified, members of the review team must screen them to determine their relevance ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). A set of predetermined rules provides a basis for including or excluding certain studies. This exercise requires a significant investment on the part of researchers, who must ensure enhanced objectivity and avoid biases or mistakes. As discussed later in this chapter, for certain types of reviews there must be at least two independent reviewers involved in the screening process and a procedure to resolve disagreements must also be in place ( Liberati et al., 2009 ; Shea et al., 2009 ). Assessing the quality of primary studies: In addition to screening material for inclusion, members of the review team may need to assess the scientific quality of the selected studies, that is, appraise the rigour of the research design and methods. Such formal assessment, which is usually conducted independently by at least two coders, helps members of the review team refine which studies to include in the final sample, determine whether or not the differences in quality may affect their conclusions, or guide how they analyze the data and interpret the findings ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2006 ). Ascribing quality scores to each primary study or considering through domain-based evaluations which study components have or have not been designed and executed appropriately makes it possible to reflect on the extent to which the selected study addresses possible biases and maximizes validity ( Shea et al., 2009 ). Extracting data: The following step involves gathering or extracting applicable information from each primary study included in the sample and deciding what is relevant to the problem of interest ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ). Indeed, the type of data that should be recorded mainly depends on the initial research questions ( Okoli & Schabram, 2010 ). However, important information may also be gathered about how, when, where and by whom the primary study was conducted, the research design and methods, or qualitative/quantitative results ( Cooper & Hedges, 2009 ). Analyzing and synthesizing data : As a final step, members of the review team must collate, summarize, aggregate, organize, and compare the evidence extracted from the included studies. The extracted data must be presented in a meaningful way that suggests a new contribution to the extant literature ( Jesson et al., 2011 ). Webster and Watson (2002) warn researchers that literature reviews should be much more than lists of papers and should provide a coherent lens to make sense of extant knowledge on a given topic. There exist several methods and techniques for synthesizing quantitative (e.g., frequency analysis, meta-analysis) and qualitative (e.g., grounded theory, narrative analysis, meta-ethnography) evidence ( Dixon-Woods, Agarwal, Jones, Young, & Sutton, 2005 ; Thomas & Harden, 2008 ).

9.3. Types of Review Articles and Brief Illustrations

EHealth researchers have at their disposal a number of approaches and methods for making sense out of existing literature, all with the purpose of casting current research findings into historical contexts or explaining contradictions that might exist among a set of primary research studies conducted on a particular topic. Our classification scheme is largely inspired from Paré and colleagues’ (2015) typology. Below we present and illustrate those review types that we feel are central to the growth and development of the eHealth domain.

9.3.1. Narrative Reviews

The narrative review is the “traditional” way of reviewing the extant literature and is skewed towards a qualitative interpretation of prior knowledge ( Sylvester et al., 2013 ). Put simply, a narrative review attempts to summarize or synthesize what has been written on a particular topic but does not seek generalization or cumulative knowledge from what is reviewed ( Davies, 2000 ; Green et al., 2006 ). Instead, the review team often undertakes the task of accumulating and synthesizing the literature to demonstrate the value of a particular point of view ( Baumeister & Leary, 1997 ). As such, reviewers may selectively ignore or limit the attention paid to certain studies in order to make a point. In this rather unsystematic approach, the selection of information from primary articles is subjective, lacks explicit criteria for inclusion and can lead to biased interpretations or inferences ( Green et al., 2006 ). There are several narrative reviews in the particular eHealth domain, as in all fields, which follow such an unstructured approach ( Silva et al., 2015 ; Paul et al., 2015 ).

Despite these criticisms, this type of review can be very useful in gathering together a volume of literature in a specific subject area and synthesizing it. As mentioned above, its primary purpose is to provide the reader with a comprehensive background for understanding current knowledge and highlighting the significance of new research ( Cronin et al., 2008 ). Faculty like to use narrative reviews in the classroom because they are often more up to date than textbooks, provide a single source for students to reference, and expose students to peer-reviewed literature ( Green et al., 2006 ). For researchers, narrative reviews can inspire research ideas by identifying gaps or inconsistencies in a body of knowledge, thus helping researchers to determine research questions or formulate hypotheses. Importantly, narrative reviews can also be used as educational articles to bring practitioners up to date with certain topics of issues ( Green et al., 2006 ).

Recently, there have been several efforts to introduce more rigour in narrative reviews that will elucidate common pitfalls and bring changes into their publication standards. Information systems researchers, among others, have contributed to advancing knowledge on how to structure a “traditional” review. For instance, Levy and Ellis (2006) proposed a generic framework for conducting such reviews. Their model follows the systematic data processing approach comprised of three steps, namely: (a) literature search and screening; (b) data extraction and analysis; and (c) writing the literature review. They provide detailed and very helpful instructions on how to conduct each step of the review process. As another methodological contribution, vom Brocke et al. (2009) offered a series of guidelines for conducting literature reviews, with a particular focus on how to search and extract the relevant body of knowledge. Last, Bandara, Miskon, and Fielt (2011) proposed a structured, predefined and tool-supported method to identify primary studies within a feasible scope, extract relevant content from identified articles, synthesize and analyze the findings, and effectively write and present the results of the literature review. We highly recommend that prospective authors of narrative reviews consult these useful sources before embarking on their work.

Darlow and Wen (2015) provide a good example of a highly structured narrative review in the eHealth field. These authors synthesized published articles that describe the development process of mobile health (m-health) interventions for patients’ cancer care self-management. As in most narrative reviews, the scope of the research questions being investigated is broad: (a) how development of these systems are carried out; (b) which methods are used to investigate these systems; and (c) what conclusions can be drawn as a result of the development of these systems. To provide clear answers to these questions, a literature search was conducted on six electronic databases and Google Scholar . The search was performed using several terms and free text words, combining them in an appropriate manner. Four inclusion and three exclusion criteria were utilized during the screening process. Both authors independently reviewed each of the identified articles to determine eligibility and extract study information. A flow diagram shows the number of studies identified, screened, and included or excluded at each stage of study selection. In terms of contributions, this review provides a series of practical recommendations for m-health intervention development.

9.3.2. Descriptive or Mapping Reviews

The primary goal of a descriptive review is to determine the extent to which a body of knowledge in a particular research topic reveals any interpretable pattern or trend with respect to pre-existing propositions, theories, methodologies or findings ( King & He, 2005 ; Paré et al., 2015 ). In contrast with narrative reviews, descriptive reviews follow a systematic and transparent procedure, including searching, screening and classifying studies ( Petersen, Vakkalanka, & Kuzniarz, 2015 ). Indeed, structured search methods are used to form a representative sample of a larger group of published works ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Further, authors of descriptive reviews extract from each study certain characteristics of interest, such as publication year, research methods, data collection techniques, and direction or strength of research outcomes (e.g., positive, negative, or non-significant) in the form of frequency analysis to produce quantitative results ( Sylvester et al., 2013 ). In essence, each study included in a descriptive review is treated as the unit of analysis and the published literature as a whole provides a database from which the authors attempt to identify any interpretable trends or draw overall conclusions about the merits of existing conceptualizations, propositions, methods or findings ( Paré et al., 2015 ). In doing so, a descriptive review may claim that its findings represent the state of the art in a particular domain ( King & He, 2005 ).

In the fields of health sciences and medical informatics, reviews that focus on examining the range, nature and evolution of a topic area are described by Anderson, Allen, Peckham, and Goodwin (2008) as mapping reviews . Like descriptive reviews, the research questions are generic and usually relate to publication patterns and trends. There is no preconceived plan to systematically review all of the literature although this can be done. Instead, researchers often present studies that are representative of most works published in a particular area and they consider a specific time frame to be mapped.

An example of this approach in the eHealth domain is offered by DeShazo, Lavallie, and Wolf (2009). The purpose of this descriptive or mapping review was to characterize publication trends in the medical informatics literature over a 20-year period (1987 to 2006). To achieve this ambitious objective, the authors performed a bibliometric analysis of medical informatics citations indexed in medline using publication trends, journal frequencies, impact factors, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) term frequencies, and characteristics of citations. Findings revealed that there were over 77,000 medical informatics articles published during the covered period in numerous journals and that the average annual growth rate was 12%. The MeSH term analysis also suggested a strong interdisciplinary trend. Finally, average impact scores increased over time with two notable growth periods. Overall, patterns in research outputs that seem to characterize the historic trends and current components of the field of medical informatics suggest it may be a maturing discipline (DeShazo et al., 2009).

9.3.3. Scoping Reviews

Scoping reviews attempt to provide an initial indication of the potential size and nature of the extant literature on an emergent topic (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Daudt, van Mossel, & Scott, 2013 ; Levac, Colquhoun, & O’Brien, 2010). A scoping review may be conducted to examine the extent, range and nature of research activities in a particular area, determine the value of undertaking a full systematic review (discussed next), or identify research gaps in the extant literature ( Paré et al., 2015 ). In line with their main objective, scoping reviews usually conclude with the presentation of a detailed research agenda for future works along with potential implications for both practice and research.

Unlike narrative and descriptive reviews, the whole point of scoping the field is to be as comprehensive as possible, including grey literature (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). Inclusion and exclusion criteria must be established to help researchers eliminate studies that are not aligned with the research questions. It is also recommended that at least two independent coders review abstracts yielded from the search strategy and then the full articles for study selection ( Daudt et al., 2013 ). The synthesized evidence from content or thematic analysis is relatively easy to present in tabular form (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Thomas & Harden, 2008 ).

One of the most highly cited scoping reviews in the eHealth domain was published by Archer, Fevrier-Thomas, Lokker, McKibbon, and Straus (2011) . These authors reviewed the existing literature on personal health record ( phr ) systems including design, functionality, implementation, applications, outcomes, and benefits. Seven databases were searched from 1985 to March 2010. Several search terms relating to phr s were used during this process. Two authors independently screened titles and abstracts to determine inclusion status. A second screen of full-text articles, again by two independent members of the research team, ensured that the studies described phr s. All in all, 130 articles met the criteria and their data were extracted manually into a database. The authors concluded that although there is a large amount of survey, observational, cohort/panel, and anecdotal evidence of phr benefits and satisfaction for patients, more research is needed to evaluate the results of phr implementations. Their in-depth analysis of the literature signalled that there is little solid evidence from randomized controlled trials or other studies through the use of phr s. Hence, they suggested that more research is needed that addresses the current lack of understanding of optimal functionality and usability of these systems, and how they can play a beneficial role in supporting patient self-management ( Archer et al., 2011 ).

9.3.4. Forms of Aggregative Reviews

Healthcare providers, practitioners, and policy-makers are nowadays overwhelmed with large volumes of information, including research-based evidence from numerous clinical trials and evaluation studies, assessing the effectiveness of health information technologies and interventions ( Ammenwerth & de Keizer, 2004 ; Deshazo et al., 2009 ). It is unrealistic to expect that all these disparate actors will have the time, skills, and necessary resources to identify the available evidence in the area of their expertise and consider it when making decisions. Systematic reviews that involve the rigorous application of scientific strategies aimed at limiting subjectivity and bias (i.e., systematic and random errors) can respond to this challenge.

Systematic reviews attempt to aggregate, appraise, and synthesize in a single source all empirical evidence that meet a set of previously specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a clearly formulated and often narrow research question on a particular topic of interest to support evidence-based practice ( Liberati et al., 2009 ). They adhere closely to explicit scientific principles ( Liberati et al., 2009 ) and rigorous methodological guidelines (Higgins & Green, 2008) aimed at reducing random and systematic errors that can lead to deviations from the truth in results or inferences. The use of explicit methods allows systematic reviews to aggregate a large body of research evidence, assess whether effects or relationships are in the same direction and of the same general magnitude, explain possible inconsistencies between study results, and determine the strength of the overall evidence for every outcome of interest based on the quality of included studies and the general consistency among them ( Cook, Mulrow, & Haynes, 1997 ). The main procedures of a systematic review involve:

- Formulating a review question and developing a search strategy based on explicit inclusion criteria for the identification of eligible studies (usually described in the context of a detailed review protocol).

- Searching for eligible studies using multiple databases and information sources, including grey literature sources, without any language restrictions.

- Selecting studies, extracting data, and assessing risk of bias in a duplicate manner using two independent reviewers to avoid random or systematic errors in the process.

- Analyzing data using quantitative or qualitative methods.

- Presenting results in summary of findings tables.

- Interpreting results and drawing conclusions.

Many systematic reviews, but not all, use statistical methods to combine the results of independent studies into a single quantitative estimate or summary effect size. Known as meta-analyses , these reviews use specific data extraction and statistical techniques (e.g., network, frequentist, or Bayesian meta-analyses) to calculate from each study by outcome of interest an effect size along with a confidence interval that reflects the degree of uncertainty behind the point estimate of effect ( Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2009 ; Deeks, Higgins, & Altman, 2008 ). Subsequently, they use fixed or random-effects analysis models to combine the results of the included studies, assess statistical heterogeneity, and calculate a weighted average of the effect estimates from the different studies, taking into account their sample sizes. The summary effect size is a value that reflects the average magnitude of the intervention effect for a particular outcome of interest or, more generally, the strength of a relationship between two variables across all studies included in the systematic review. By statistically combining data from multiple studies, meta-analyses can create more precise and reliable estimates of intervention effects than those derived from individual studies alone, when these are examined independently as discrete sources of information.

The review by Gurol-Urganci, de Jongh, Vodopivec-Jamsek, Atun, and Car (2013) on the effects of mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at healthcare appointments is an illustrative example of a high-quality systematic review with meta-analysis. Missed appointments are a major cause of inefficiency in healthcare delivery with substantial monetary costs to health systems. These authors sought to assess whether mobile phone-based appointment reminders delivered through Short Message Service ( sms ) or Multimedia Messaging Service ( mms ) are effective in improving rates of patient attendance and reducing overall costs. To this end, they conducted a comprehensive search on multiple databases using highly sensitive search strategies without language or publication-type restrictions to identify all rct s that are eligible for inclusion. In order to minimize the risk of omitting eligible studies not captured by the original search, they supplemented all electronic searches with manual screening of trial registers and references contained in the included studies. Study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias assessments were performed independently by two coders using standardized methods to ensure consistency and to eliminate potential errors. Findings from eight rct s involving 6,615 participants were pooled into meta-analyses to calculate the magnitude of effects that mobile text message reminders have on the rate of attendance at healthcare appointments compared to no reminders and phone call reminders.

Meta-analyses are regarded as powerful tools for deriving meaningful conclusions. However, there are situations in which it is neither reasonable nor appropriate to pool studies together using meta-analytic methods simply because there is extensive clinical heterogeneity between the included studies or variation in measurement tools, comparisons, or outcomes of interest. In these cases, systematic reviews can use qualitative synthesis methods such as vote counting, content analysis, classification schemes and tabulations, as an alternative approach to narratively synthesize the results of the independent studies included in the review. This form of review is known as qualitative systematic review.

A rigorous example of one such review in the eHealth domain is presented by Mickan, Atherton, Roberts, Heneghan, and Tilson (2014) on the use of handheld computers by healthcare professionals and their impact on access to information and clinical decision-making. In line with the methodological guidelines for systematic reviews, these authors: (a) developed and registered with prospero ( www.crd.york.ac.uk/ prospero / ) an a priori review protocol; (b) conducted comprehensive searches for eligible studies using multiple databases and other supplementary strategies (e.g., forward searches); and (c) subsequently carried out study selection, data extraction, and risk of bias assessments in a duplicate manner to eliminate potential errors in the review process. Heterogeneity between the included studies in terms of reported outcomes and measures precluded the use of meta-analytic methods. To this end, the authors resorted to using narrative analysis and synthesis to describe the effectiveness of handheld computers on accessing information for clinical knowledge, adherence to safety and clinical quality guidelines, and diagnostic decision-making.

In recent years, the number of systematic reviews in the field of health informatics has increased considerably. Systematic reviews with discordant findings can cause great confusion and make it difficult for decision-makers to interpret the review-level evidence ( Moher, 2013 ). Therefore, there is a growing need for appraisal and synthesis of prior systematic reviews to ensure that decision-making is constantly informed by the best available accumulated evidence. Umbrella reviews , also known as overviews of systematic reviews, are tertiary types of evidence synthesis that aim to accomplish this; that is, they aim to compare and contrast findings from multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses ( Becker & Oxman, 2008 ). Umbrella reviews generally adhere to the same principles and rigorous methodological guidelines used in systematic reviews. However, the unit of analysis in umbrella reviews is the systematic review rather than the primary study ( Becker & Oxman, 2008 ). Unlike systematic reviews that have a narrow focus of inquiry, umbrella reviews focus on broader research topics for which there are several potential interventions ( Smith, Devane, Begley, & Clarke, 2011 ). A recent umbrella review on the effects of home telemonitoring interventions for patients with heart failure critically appraised, compared, and synthesized evidence from 15 systematic reviews to investigate which types of home telemonitoring technologies and forms of interventions are more effective in reducing mortality and hospital admissions ( Kitsiou, Paré, & Jaana, 2015 ).

9.3.5. Realist Reviews

Realist reviews are theory-driven interpretative reviews developed to inform, enhance, or supplement conventional systematic reviews by making sense of heterogeneous evidence about complex interventions applied in diverse contexts in a way that informs policy decision-making ( Greenhalgh, Wong, Westhorp, & Pawson, 2011 ). They originated from criticisms of positivist systematic reviews which centre on their “simplistic” underlying assumptions ( Oates, 2011 ). As explained above, systematic reviews seek to identify causation. Such logic is appropriate for fields like medicine and education where findings of randomized controlled trials can be aggregated to see whether a new treatment or intervention does improve outcomes. However, many argue that it is not possible to establish such direct causal links between interventions and outcomes in fields such as social policy, management, and information systems where for any intervention there is unlikely to be a regular or consistent outcome ( Oates, 2011 ; Pawson, 2006 ; Rousseau, Manning, & Denyer, 2008 ).

To circumvent these limitations, Pawson, Greenhalgh, Harvey, and Walshe (2005) have proposed a new approach for synthesizing knowledge that seeks to unpack the mechanism of how “complex interventions” work in particular contexts. The basic research question — what works? — which is usually associated with systematic reviews changes to: what is it about this intervention that works, for whom, in what circumstances, in what respects and why? Realist reviews have no particular preference for either quantitative or qualitative evidence. As a theory-building approach, a realist review usually starts by articulating likely underlying mechanisms and then scrutinizes available evidence to find out whether and where these mechanisms are applicable ( Shepperd et al., 2009 ). Primary studies found in the extant literature are viewed as case studies which can test and modify the initial theories ( Rousseau et al., 2008 ).

The main objective pursued in the realist review conducted by Otte-Trojel, de Bont, Rundall, and van de Klundert (2014) was to examine how patient portals contribute to health service delivery and patient outcomes. The specific goals were to investigate how outcomes are produced and, most importantly, how variations in outcomes can be explained. The research team started with an exploratory review of background documents and research studies to identify ways in which patient portals may contribute to health service delivery and patient outcomes. The authors identified six main ways which represent “educated guesses” to be tested against the data in the evaluation studies. These studies were identified through a formal and systematic search in four databases between 2003 and 2013. Two members of the research team selected the articles using a pre-established list of inclusion and exclusion criteria and following a two-step procedure. The authors then extracted data from the selected articles and created several tables, one for each outcome category. They organized information to bring forward those mechanisms where patient portals contribute to outcomes and the variation in outcomes across different contexts.

9.3.6. Critical Reviews

Lastly, critical reviews aim to provide a critical evaluation and interpretive analysis of existing literature on a particular topic of interest to reveal strengths, weaknesses, contradictions, controversies, inconsistencies, and/or other important issues with respect to theories, hypotheses, research methods or results ( Baumeister & Leary, 1997 ; Kirkevold, 1997 ). Unlike other review types, critical reviews attempt to take a reflective account of the research that has been done in a particular area of interest, and assess its credibility by using appraisal instruments or critical interpretive methods. In this way, critical reviews attempt to constructively inform other scholars about the weaknesses of prior research and strengthen knowledge development by giving focus and direction to studies for further improvement ( Kirkevold, 1997 ).

Kitsiou, Paré, and Jaana (2013) provide an example of a critical review that assessed the methodological quality of prior systematic reviews of home telemonitoring studies for chronic patients. The authors conducted a comprehensive search on multiple databases to identify eligible reviews and subsequently used a validated instrument to conduct an in-depth quality appraisal. Results indicate that the majority of systematic reviews in this particular area suffer from important methodological flaws and biases that impair their internal validity and limit their usefulness for clinical and decision-making purposes. To this end, they provide a number of recommendations to strengthen knowledge development towards improving the design and execution of future reviews on home telemonitoring.

9.4. Summary

Table 9.1 outlines the main types of literature reviews that were described in the previous sub-sections and summarizes the main characteristics that distinguish one review type from another. It also includes key references to methodological guidelines and useful sources that can be used by eHealth scholars and researchers for planning and developing reviews.

Typology of Literature Reviews (adapted from Paré et al., 2015).

As shown in Table 9.1 , each review type addresses different kinds of research questions or objectives, which subsequently define and dictate the methods and approaches that need to be used to achieve the overarching goal(s) of the review. For example, in the case of narrative reviews, there is greater flexibility in searching and synthesizing articles ( Green et al., 2006 ). Researchers are often relatively free to use a diversity of approaches to search, identify, and select relevant scientific articles, describe their operational characteristics, present how the individual studies fit together, and formulate conclusions. On the other hand, systematic reviews are characterized by their high level of systematicity, rigour, and use of explicit methods, based on an “a priori” review plan that aims to minimize bias in the analysis and synthesis process (Higgins & Green, 2008). Some reviews are exploratory in nature (e.g., scoping/mapping reviews), whereas others may be conducted to discover patterns (e.g., descriptive reviews) or involve a synthesis approach that may include the critical analysis of prior research ( Paré et al., 2015 ). Hence, in order to select the most appropriate type of review, it is critical to know before embarking on a review project, why the research synthesis is conducted and what type of methods are best aligned with the pursued goals.

9.5. Concluding Remarks

In light of the increased use of evidence-based practice and research generating stronger evidence ( Grady et al., 2011 ; Lyden et al., 2013 ), review articles have become essential tools for summarizing, synthesizing, integrating or critically appraising prior knowledge in the eHealth field. As mentioned earlier, when rigorously conducted review articles represent powerful information sources for eHealth scholars and practitioners looking for state-of-the-art evidence. The typology of literature reviews we used herein will allow eHealth researchers, graduate students and practitioners to gain a better understanding of the similarities and differences between review types.

We must stress that this classification scheme does not privilege any specific type of review as being of higher quality than another ( Paré et al., 2015 ). As explained above, each type of review has its own strengths and limitations. Having said that, we realize that the methodological rigour of any review — be it qualitative, quantitative or mixed — is a critical aspect that should be considered seriously by prospective authors. In the present context, the notion of rigour refers to the reliability and validity of the review process described in section 9.2. For one thing, reliability is related to the reproducibility of the review process and steps, which is facilitated by a comprehensive documentation of the literature search process, extraction, coding and analysis performed in the review. Whether the search is comprehensive or not, whether it involves a methodical approach for data extraction and synthesis or not, it is important that the review documents in an explicit and transparent manner the steps and approach that were used in the process of its development. Next, validity characterizes the degree to which the review process was conducted appropriately. It goes beyond documentation and reflects decisions related to the selection of the sources, the search terms used, the period of time covered, the articles selected in the search, and the application of backward and forward searches ( vom Brocke et al., 2009 ). In short, the rigour of any review article is reflected by the explicitness of its methods (i.e., transparency) and the soundness of the approach used. We refer those interested in the concepts of rigour and quality to the work of Templier and Paré (2015) which offers a detailed set of methodological guidelines for conducting and evaluating various types of review articles.

To conclude, our main objective in this chapter was to demystify the various types of literature reviews that are central to the continuous development of the eHealth field. It is our hope that our descriptive account will serve as a valuable source for those conducting, evaluating or using reviews in this important and growing domain.

- Ammenwerth E., de Keizer N. An inventory of evaluation studies of information technology in health care. Trends in evaluation research, 1982-2002. International Journal of Medical Informatics. 2004; 44 (1):44–56. [ PubMed : 15778794 ]

- Anderson S., Allen P., Peckham S., Goodwin N. Asking the right questions: scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2008; 6 (7):1–12. [ PMC free article : PMC2500008 ] [ PubMed : 18613961 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Archer N., Fevrier-Thomas U., Lokker C., McKibbon K. A., Straus S.E. Personal health records: a scoping review. Journal of American Medical Informatics Association. 2011; 18 (4):515–522. [ PMC free article : PMC3128401 ] [ PubMed : 21672914 ]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005; 8 (1):19–32.

- A systematic, tool-supported method for conducting literature reviews in information systems. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 19th European Conference on Information Systems ( ecis 2011); June 9 to 11; Helsinki, Finland. 2011.

- Baumeister R. F., Leary M.R. Writing narrative literature reviews. Review of General Psychology. 1997; 1 (3):311–320.

- Becker L. A., Oxman A.D. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Higgins J. P. T., Green S., editors. Hoboken, nj : John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2008. Overviews of reviews; pp. 607–631.

- Borenstein M., Hedges L., Higgins J., Rothstein H. Introduction to meta-analysis. Hoboken, nj : John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2009.

- Cook D. J., Mulrow C. D., Haynes B. Systematic reviews: Synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997; 126 (5):376–380. [ PubMed : 9054282 ]

- Cooper H., Hedges L.V. In: The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. 2nd ed. Cooper H., Hedges L. V., Valentine J. C., editors. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2009. Research synthesis as a scientific process; pp. 3–17.

- Cooper H. M. Organizing knowledge syntheses: A taxonomy of literature reviews. Knowledge in Society. 1988; 1 (1):104–126.

- Cronin P., Ryan F., Coughlan M. Undertaking a literature review: a step-by-step approach. British Journal of Nursing. 2008; 17 (1):38–43. [ PubMed : 18399395 ]

- Darlow S., Wen K.Y. Development testing of mobile health interventions for cancer patient self-management: A review. Health Informatics Journal. 2015 (online before print). [ PubMed : 25916831 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Daudt H. M., van Mossel C., Scott S.J. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. bmc Medical Research Methodology. 2013; 13 :48. [ PMC free article : PMC3614526 ] [ PubMed : 23522333 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Davies P. The relevance of systematic reviews to educational policy and practice. Oxford Review of Education. 2000; 26 (3-4):365–378.

- Deeks J. J., Higgins J. P. T., Altman D.G. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Higgins J. P. T., Green S., editors. Hoboken, nj : John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2008. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses; pp. 243–296.

- Deshazo J. P., Lavallie D. L., Wolf F.M. Publication trends in the medical informatics literature: 20 years of “Medical Informatics” in mesh . bmc Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2009; 9 :7. [ PMC free article : PMC2652453 ] [ PubMed : 19159472 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dixon-Woods M., Agarwal S., Jones D., Young B., Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy. 2005; 10 (1):45–53. [ PubMed : 15667704 ]

- Finfgeld-Connett D., Johnson E.D. Literature search strategies for conducting knowledge-building and theory-generating qualitative systematic reviews. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2013; 69 (1):194–204. [ PMC free article : PMC3424349 ] [ PubMed : 22591030 ]

- Grady B., Myers K. M., Nelson E. L., Belz N., Bennett L., Carnahan L. … Guidelines Working Group. Evidence-based practice for telemental health. Telemedicine Journal and E Health. 2011; 17 (2):131–148. [ PubMed : 21385026 ]

- Green B. N., Johnson C. D., Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine. 2006; 5 (3):101–117. [ PMC free article : PMC2647067 ] [ PubMed : 19674681 ]

- Greenhalgh T., Wong G., Westhorp G., Pawson R. Protocol–realist and meta-narrative evidence synthesis: evolving standards ( rameses ). bmc Medical Research Methodology. 2011; 11 :115. [ PMC free article : PMC3173389 ] [ PubMed : 21843376 ]

- Gurol-Urganci I., de Jongh T., Vodopivec-Jamsek V., Atun R., Car J. Mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at healthcare appointments. Cochrane Database System Review. 2013; 12 cd 007458. [ PMC free article : PMC6485985 ] [ PubMed : 24310741 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hart C. Doing a literature review: Releasing the social science research imagination. London: SAGE Publications; 1998.

- Higgins J. P. T., Green S., editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: Cochrane book series. Hoboken, nj : Wiley-Blackwell; 2008.

- Jesson J., Matheson L., Lacey F.M. Doing your literature review: traditional and systematic techniques. Los Angeles & London: SAGE Publications; 2011.

- King W. R., He J. Understanding the role and methods of meta-analysis in IS research. Communications of the Association for Information Systems. 2005; 16 :1.

- Kirkevold M. Integrative nursing research — an important strategy to further the development of nursing science and nursing practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997; 25 (5):977–984. [ PubMed : 9147203 ]

- Kitchenham B., Charters S. ebse Technical Report Version 2.3. Keele & Durham. uk : Keele University & University of Durham; 2007. Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering.

- Kitsiou S., Paré G., Jaana M. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of home telemonitoring interventions for patients with chronic diseases: a critical assessment of their methodological quality. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2013; 15 (7):e150. [ PMC free article : PMC3785977 ] [ PubMed : 23880072 ]

- Kitsiou S., Paré G., Jaana M. Effects of home telemonitoring interventions on patients with chronic heart failure: an overview of systematic reviews. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2015; 17 (3):e63. [ PMC free article : PMC4376138 ] [ PubMed : 25768664 ]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O’Brien K. K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Science. 2010; 5 (1):69. [ PMC free article : PMC2954944 ] [ PubMed : 20854677 ]

- Levy Y., Ellis T.J. A systems approach to conduct an effective literature review in support of information systems research. Informing Science. 2006; 9 :181–211.

- Liberati A., Altman D. G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gøtzsche P. C., Ioannidis J. P. A. et al. Moher D. The prisma statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009; 151 (4):W-65. [ PubMed : 19622512 ]

- Lyden J. R., Zickmund S. L., Bhargava T. D., Bryce C. L., Conroy M. B., Fischer G. S. et al. McTigue K. M. Implementing health information technology in a patient-centered manner: Patient experiences with an online evidence-based lifestyle intervention. Journal for Healthcare Quality. 2013; 35 (5):47–57. [ PubMed : 24004039 ]

- Mickan S., Atherton H., Roberts N. W., Heneghan C., Tilson J.K. Use of handheld computers in clinical practice: a systematic review. bmc Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2014; 14 :56. [ PMC free article : PMC4099138 ] [ PubMed : 24998515 ]

- Moher D. The problem of duplicate systematic reviews. British Medical Journal. 2013; 347 (5040) [ PubMed : 23945367 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Montori V. M., Wilczynski N. L., Morgan D., Haynes R. B., Hedges T. Systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study of location and citation counts. bmc Medicine. 2003; 1 :2. [ PMC free article : PMC281591 ] [ PubMed : 14633274 ]

- Mulrow C. D. The medical review article: state of the science. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1987; 106 (3):485–488. [ PubMed : 3813259 ] [ CrossRef ]

- Evidence-based information systems: A decade later. Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems ; 2011. Retrieved from http://aisel .aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent .cgi?article =1221&context =ecis2011 .

- Okoli C., Schabram K. A guide to conducting a systematic literature review of information systems research. ssrn Electronic Journal. 2010

- Otte-Trojel T., de Bont A., Rundall T. G., van de Klundert J. How outcomes are achieved through patient portals: a realist review. Journal of American Medical Informatics Association. 2014; 21 (4):751–757. [ PMC free article : PMC4078283 ] [ PubMed : 24503882 ]

- Paré G., Trudel M.-C., Jaana M., Kitsiou S. Synthesizing information systems knowledge: A typology of literature reviews. Information & Management. 2015; 52 (2):183–199.

- Patsopoulos N. A., Analatos A. A., Ioannidis J.P. A. Relative citation impact of various study designs in the health sciences. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005; 293 (19):2362–2366. [ PubMed : 15900006 ]

- Paul M. M., Greene C. M., Newton-Dame R., Thorpe L. E., Perlman S. E., McVeigh K. H., Gourevitch M.N. The state of population health surveillance using electronic health records: A narrative review. Population Health Management. 2015; 18 (3):209–216. [ PubMed : 25608033 ]

- Pawson R. Evidence-based policy: a realist perspective. London: SAGE Publications; 2006.

- Pawson R., Greenhalgh T., Harvey G., Walshe K. Realist review—a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy. 2005; 10 (Suppl 1):21–34. [ PubMed : 16053581 ]

- Petersen K., Vakkalanka S., Kuzniarz L. Guidelines for conducting systematic mapping studies in software engineering: An update. Information and Software Technology. 2015; 64 :1–18.

- Petticrew M., Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. Malden, ma : Blackwell Publishing Co; 2006.

- Rousseau D. M., Manning J., Denyer D. Evidence in management and organizational science: Assembling the field’s full weight of scientific knowledge through syntheses. The Academy of Management Annals. 2008; 2 (1):475–515.

- Rowe F. What literature review is not: diversity, boundaries and recommendations. European Journal of Information Systems. 2014; 23 (3):241–255.

- Shea B. J., Hamel C., Wells G. A., Bouter L. M., Kristjansson E., Grimshaw J. et al. Boers M. amstar is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009; 62 (10):1013–1020. [ PubMed : 19230606 ]

- Shepperd S., Lewin S., Straus S., Clarke M., Eccles M. P., Fitzpatrick R. et al. Sheikh A. Can we systematically review studies that evaluate complex interventions? PLoS Medicine. 2009; 6 (8):e1000086. [ PMC free article : PMC2717209 ] [ PubMed : 19668360 ]

- Silva B. M., Rodrigues J. J., de la Torre Díez I., López-Coronado M., Saleem K. Mobile-health: A review of current state in 2015. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2015; 56 :265–272. [ PubMed : 26071682 ]

- Smith V., Devane D., Begley C., Clarke M. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. bmc Medical Research Methodology. 2011; 11 (1):15. [ PMC free article : PMC3039637 ] [ PubMed : 21291558 ]

- Sylvester A., Tate M., Johnstone D. Beyond synthesis: re-presenting heterogeneous research literature. Behaviour & Information Technology. 2013; 32 (12):1199–1215.

- Templier M., Paré G. A framework for guiding and evaluating literature reviews. Communications of the Association for Information Systems. 2015; 37 (6):112–137.

- Thomas J., Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. bmc Medical Research Methodology. 2008; 8 (1):45. [ PMC free article : PMC2478656 ] [ PubMed : 18616818 ]

- Reconstructing the giant: on the importance of rigour in documenting the literature search process. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 17th European Conference on Information Systems ( ecis 2009); Verona, Italy. 2009.

- Webster J., Watson R.T. Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. Management Information Systems Quarterly. 2002; 26 (2):11.

- Whitlock E. P., Lin J. S., Chou R., Shekelle P., Robinson K.A. Using existing systematic reviews in complex systematic reviews. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008; 148 (10):776–782. [ PubMed : 18490690 ]

This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons License, Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0): see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

- Cite this Page Paré G, Kitsiou S. Chapter 9 Methods for Literature Reviews. In: Lau F, Kuziemsky C, editors. Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach [Internet]. Victoria (BC): University of Victoria; 2017 Feb 27.

- PDF version of this title (4.5M)

In this Page

- Introduction

- Overview of the Literature Review Process and Steps

- Types of Review Articles and Brief Illustrations

- Concluding Remarks

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Recent Activity

- Chapter 9 Methods for Literature Reviews - Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Ev... Chapter 9 Methods for Literature Reviews - Handbook of eHealth Evaluation: An Evidence-based Approach

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Learning objectives.

At the conclusion of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify the purpose of the literature review in the research process

- Distinguish between different types of literature reviews

1.1 What is a Literature Review?

Pick up nearly any book on research methods and you will find a description of a literature review. At a basic level, the term implies a survey of factual or nonfiction books, articles, and other documents published on a particular subject. Definitions may be similar across the disciplines, with new types and definitions continuing to emerge. Generally speaking, a literature review is a:

- “comprehensive background of the literature within the interested topic area…” ( O’Gorman & MacIntosh, 2015, p. 31 ).

- “critical component of the research process that provides an in-depth analysis of recently published research findings in specifically identified areas of interest.” ( House, 2018, p. 109 ).

- “written document that presents a logically argued case founded on a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge about a topic of study” ( Machi & McEvoy, 2012, p. 4 ).

As a foundation for knowledge advancement in every discipline, it is an important element of any research project. At the graduate or doctoral level, the literature review is an essential feature of thesis and dissertation, as well as grant proposal writing. That is to say, “A substantive, thorough, sophisticated literature review is a precondition for doing substantive, thorough, sophisticated research…A researcher cannot perform significant research without first understanding the literature in the field.” ( Boote & Beile, 2005, p. 3 ). It is by this means, that a researcher demonstrates familiarity with a body of knowledge and thereby establishes credibility with a reader. An advanced-level literature review shows how prior research is linked to a new project, summarizing and synthesizing what is known while identifying gaps in the knowledge base, facilitating theory development, closing areas where enough research already exists, and uncovering areas where more research is needed. ( Webster & Watson, 2002, p. xiii )

A graduate-level literature review is a compilation of the most significant previously published research on your topic. Unlike an annotated bibliography or a research paper you may have written as an undergraduate, your literature review will outline, evaluate and synthesize relevant research and relate those sources to your own thesis or research question. It is much more than a summary of all the related literature.

It is a type of writing that demonstrate the importance of your research by defining the main ideas and the relationship between them. A good literature review lays the foundation for the importance of your stated problem and research question.

Literature reviews:

- define a concept

- map the research terrain or scope

- systemize relationships between concepts

- identify gaps in the literature ( Rocco & Plathotnik, 2009, p. 128 )

The purpose of a literature review is to demonstrate that your research question is meaningful. Additionally, you may review the literature of different disciplines to find deeper meaning and understanding of your topic. It is especially important to consider other disciplines when you do not find much on your topic in one discipline. You will need to search the cognate literature before claiming there is “little previous research” on your topic.

Well developed literature reviews involve numerous steps and activities. The literature review is an iterative process because you will do at least two of them: a preliminary search to learn what has been published in your area and whether there is sufficient support in the literature for moving ahead with your subject. After this first exploration, you will conduct a deeper dive into the literature to learn everything you can about the topic and its related issues.

Literature Review Tutorial

1.2 Literature Review Basics

An effective literature review must:

- Methodologically analyze and synthesize quality literature on a topic

- Provide a firm foundation to a topic or research area

- Provide a firm foundation for the selection of a research methodology

- Demonstrate that the proposed research contributes something new to the overall body of knowledge of advances the research field’s knowledge base. ( Levy & Ellis, 2006 ).

All literature reviews, whether they are qualitative, quantitative or both, will at some point:

- Introduce the topic and define its key terms

- Establish the importance of the topic

- Provide an overview of the amount of available literature and its types (for example: theoretical, statistical, speculative)

- Identify gaps in the literature

- Point out consistent finding across studies

- Arrive at a synthesis that organizes what is known about a topic

- Discusses possible implications and directions for future research

1.3 Types of Literature Reviews

There are many different types of literature reviews, however there are some shared characteristics or features. Remember a comprehensive literature review is, at its most fundamental level, an original work based on an extensive critical examination and synthesis of the relevant literature on a topic. As a study of the research on a particular topic, it is arranged by key themes or findings, which may lead up to or link to the research question. In some cases, the research question will drive the type of literature review that is undertaken.

The following section includes brief descriptions of the terms used to describe different literature review types with examples of each. The included citations are open access, Creative Commons licensed or copyright-restricted.

1.3.1 Types of Review

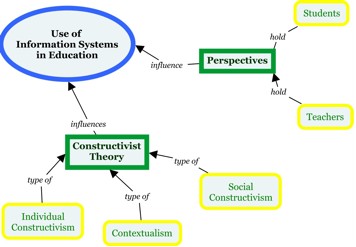

1.3.1.1 conceptual.

Guided by an understanding of basic issues rather than a research methodology. You are looking for key factors, concepts or variables and the presumed relationship between them. The goal of the conceptual literature review is to categorize and describe concepts relevant to your study or topic and outline a relationship between them. You will include relevant theory and empirical research.

Examples of a Conceptual Review:

- Education : The formality of learning science in everyday life: A conceptual literature review. ( Dohn, 2010 ).

- Education : Are we asking the right questions? A conceptual review of the educational development literature in higher education. ( Amundsen & Wilson, 2012 ).

1.3.1.2 Empirical

An empirical literature review collects, creates, arranges, and analyzes numeric data reflecting the frequency of themes, topics, authors and/or methods found in existing literature. Empirical literature reviews present their summaries in quantifiable terms using descriptive and inferential statistics.

Examples of an Empirical Review:

- Nursing : False-positive findings in Cochrane meta-analyses with and without application of trial sequential analysis: An empirical review. ( Imberger, Thorlund, Gluud, & Wettersley, 2016 ).

- Education : Impediments of e-learning adoption in higher learning institutions of Tanzania: An empirical review ( Mwakyusa & Mwalyagile, 2016 ).

1.3.1.3 Exploratory

Unlike a synoptic literature review, the purpose here is to provide a broad approach to the topic area. The aim is breadth rather than depth and to get a general feel for the size of the topic area. A graduate student might do an exploratory review of the literature before beginning a synoptic, or more comprehensive one.

Examples of an Exploratory Review:

- Education : University research management: An exploratory literature review. ( Schuetzenmeister, 2010 ).

- Education : An exploratory review of design principles in constructivist gaming learning environments. ( Rosario & Widmeyer, 2009 ).

1.3.1.4 Focused

A type of literature review limited to a single aspect of previous research, such as methodology. A focused literature review generally will describe the implications of choosing a particular element of past research, such as methodology in terms of data collection, analysis and interpretation.

Examples of a Focused Review:

- Nursing : Clinical inertia in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A focused literature review. ( Khunti, Davies, & Khunti, 2015 ).

- Education : Language awareness: Genre awareness-a focused review of the literature. ( Stainton, 1992 ).

1.3.1.5 Integrative

Critiques past research and draws overall conclusions from the body of literature at a specified point in time. Reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way. Most integrative reviews are intended to address mature topics or emerging topics. May require the author to adopt a guiding theory, a set of competing models, or a point of view about a topic. For more description of integrative reviews, see Whittemore & Knafl (2005).

Examples of an Integrative Review:

- Nursing : Interprofessional teamwork and collaboration between community health workers and healthcare teams: An integrative review. ( Franklin, Bernhardt, Lopez, Long-Middleton, & Davis, 2015 ).

- Education : Exploring the gap between teacher certification and permanent employment in Ontario: An integrative literature review. ( Brock & Ryan, 2016 ).

1.3.1.6 Meta-analysis

A subset of a systematic review, that takes findings from several studies on the same subject and analyzes them using standardized statistical procedures to pool together data. Integrates findings from a large body of quantitative findings to enhance understanding, draw conclusions, and detect patterns and relationships. Gather data from many different, independent studies that look at the same research question and assess similar outcome measures. Data is combined and re-analyzed, providing a greater statistical power than any single study alone. It’s important to note that not every systematic review includes a meta-analysis but a meta-analysis can’t exist without a systematic review of the literature.

Examples of a Meta-Analysis:

- Education : Efficacy of the cooperative learning method on mathematics achievement and attitude: A meta-analysis research. ( Capar & Tarim, 2015 ).

- Nursing : A meta-analysis of the effects of non-traditional teaching methods on the critical thinking abilities of nursing students. ( Lee, Lee, Gong, Bae, & Choi, 2016 ).

- Education : Gender differences in student attitudes toward science: A meta-analysis of the literature from 1970 to 1991. ( Weinburgh, 1995 ).

1.3.1.7 Narrative/Traditional

An overview of research on a particular topic that critiques and summarizes a body of literature. Typically broad in focus. Relevant past research is selected and synthesized into a coherent discussion. Methodologies, findings and limits of the existing body of knowledge are discussed in narrative form. Sometimes also referred to as a traditional literature review. Requires a sufficiently focused research question. The process may be subject to bias that supports the researcher’s own work.

Examples of a Narrative/Traditional Review:

- Nursing : Family carers providing support to a person dying in the home setting: A narrative literature review. ( Morris, King, Turner, & Payne, 2015 ).

- Education : Adventure education and Outward Bound: Out-of-class experiences that make a lasting difference. ( Hattie, Marsh, Neill, & Richards, 1997 ).

- Education : Good quality discussion is necessary but not sufficient in asynchronous tuition: A brief narrative review of the literature. ( Fear & Erikson-Brown, 2014 ).

- Nursing : Outcomes of physician job satisfaction: A narrative review, implications, and directions for future research. ( Williams & Skinner, 2003 ).

1.3.1.8 Realist

Aspecific type of literature review that is theory-driven and interpretative and is intended to explain the outcomes of a complex intervention program(s).

Examples of a Realist Review:

- Nursing : Lean thinking in healthcare: A realist review of the literature. ( Mazzacato, Savage, Brommels, 2010 ).

- Education : Unravelling quality culture in higher education: A realist review. ( Bendermacher, Egbrink, Wolfhagen, & Dolmans, 2017 ).

1.3.1.9 Scoping

Tend to be non-systematic and focus on breadth of coverage conducted on a topic rather than depth. Utilize a wide range of materials; may not evaluate the quality of the studies as much as count the number. One means of understanding existing literature. Aims to identify nature and extent of research; preliminary assessment of size and scope of available research on topic. May include research in progress.

Examples of a Scoping Review:

- Nursing : Organizational interventions improving access to community-based primary health care for vulnerable populations: A scoping review. ( Khanassov, Pluye, Descoteaux, Haggerty, Russell, Gunn, & Levesque, 2016 ).

- Education : Interdisciplinary doctoral research supervision: A scoping review. ( Vanstone, Hibbert, Kinsella, McKenzie, Pitman, & Lingard, 2013 ).

- Nursing : A scoping review of the literature on the abolition of user fees in health care services in Africa. ( Ridde, & Morestin, 2011 ).

1.3.1.10 Synoptic

Unlike an exploratory review, the purpose is to provide a concise but accurate overview of all material that appears to be relevant to a chosen topic. Both content and methodological material is included. The review should aim to be both descriptive and evaluative. Summarizes previous studies while also showing how the body of literature could be extended and improved in terms of content and method by identifying gaps.

Examples of a Synoptic Review:

- Education : Theoretical framework for educational assessment: A synoptic review. ( Ghaicha, 2016 ).

- Education : School effects research: A synoptic review of past efforts and some suggestions for the future. ( Cuttance, 1981 ).

1.3.1.11 Systematic Review

A rigorous review that follows a strict methodology designed with a presupposed selection of literature reviewed. Undertaken to clarify the state of existing research, the evidence, and possible implications that can be drawn from that. Using comprehensive and exhaustive searching of the published and unpublished literature, searching various databases, reports, and grey literature. Transparent and reproducible in reporting details of time frame, search and methods to minimize bias. Must include a team of at least 2-3 and includes the critical appraisal of the literature. For more description of systematic reviews, including links to protocols, checklists, workflow processes, and structure see “ A Young Researcher’s Guide to a Systematic Review “.

Examples of a Systematic Review:

- Education : The potentials of using cloud computing in schools: A systematic literature review ( Hartmann, Braae, Pedersen, & Khalid, 2017 )

- Nursing : Is butter back? A systematic review and meta-analysis of butter consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and total mortality. ( Pimpin, Wu, Haskelberg, Del Gobbo, & Mozaffarian, 2016 ).

- Education : The use of research to improve professional practice: a systematic review of the literature. ( Hemsley-Brown & Sharp, 2003 ).

- Nursing : Using computers to self-manage type 2 diabetes. ( Pal, Eastwood, Michie, Farmer, Barnard, Peacock, Wood, Inniss, & Murray, 2013 ).

1.3.1.12 Umbrella/Overview of Reviews

Compiles evidence from multiple systematic reviews into one document. Focuses on broad condition or problem for which there are competing interventions and highlights reviews that address those interventions and their effects. Often used in recommendations for practice.

Examples of an Umbrella/Overview Review:

- Education : Reflective practice in healthcare education: An umbrella review. ( Fragknos, 2016 ).

- Nursing : Systematic reviews of psychosocial interventions for autism: an umbrella review. ( Seida, Ospina, Karkhaneh, Hartling, Smith, & Clark, 2009 ).

For a brief discussion see “ Not all literature reviews are the same ” (Thomson, 2013).

1.4 Why do a Literature Review?

The purpose of the literature review is the same regardless of the topic or research method. It tests your own research question against what is already known about the subject.

1.4.1 First – It’s part of the whole. Omission of a literature review chapter or section in a graduate-level project represents a serious void or absence of critical element in the research process.

The outcome of your review is expected to demonstrate that you:

- can systematically explore the research in your topic area

- can read and critically analyze the literature in your discipline and then use it appropriately to advance your own work

- have sufficient knowledge in the topic to undertake further investigation

1.4.2 Second – It’s good for you!

- You improve your skills as a researcher

- You become familiar with the discourse of your discipline and learn how to be a scholar in your field

- You learn through writing your ideas and finding your voice in your subject area

- You define, redefine and clarify your research question for yourself in the process

1.4.3 Third – It’s good for your reader. Your reader expects you to have done the hard work of gathering, evaluating and synthesizes the literature. When you do a literature review you:

- Set the context for the topic and present its significance

- Identify what’s important to know about your topic – including individual material, prior research, publications, organizations and authors.

- Demonstrate relationships among prior research

- Establish limitations of existing knowledge

- Analyze trends in the topic’s treatment and gaps in the literature

1.4.4 Why do a literature review?

- To locate gaps in the literature of your discipline

- To avoid reinventing the wheel

- To carry on where others have already been

- To identify other people working in the same field

- To increase your breadth of knowledge in your subject area

- To find the seminal works in your field

- To provide intellectual context for your own work

- To acknowledge opposing viewpoints

- To put your work in perspective

- To demonstrate you can discover and retrieve previous work in the area

1.5 Common Literature Review Errors

Graduate-level literature reviews are more than a summary of the publications you find on a topic. As you have seen in this brief introduction, literature reviews are a very specific type of research, analysis, and writing. We will explore these topics more in the next chapters. Some things to keep in mind as you begin your own research and writing are ways to avoid the most common errors seen in the first attempt at a literature review. For a quick review of some of the pitfalls and challenges a new researcher faces when he/she begins work, see “ Get Ready: Academic Writing, General Pitfalls and (oh yes) Getting Started! ”.

As you begin your own graduate-level literature review, try to avoid these common mistakes:

- Accepts another researcher’s finding as valid without evaluating methodology and data

- Contrary findings and alternative interpretations are not considered or mentioned

- Findings are not clearly related to one’s own study, or findings are too general

- Insufficient time allowed to define best search strategies and writing

- Isolated statistical results are simply reported rather than synthesizing the results

- Problems with selecting and using most relevant keywords, subject headings and descriptors

- Relies too heavily on secondary sources

- Search methods are not recorded or reported for transparency

- Summarizes rather than synthesizes articles

In conclusion, the purpose of a literature review is three-fold:

- to survey the current state of knowledge or evidence in the area of inquiry,

- to identify key authors, articles, theories, and findings in that area, and

- to identify gaps in knowledge in that research area.

A literature review is commonly done today using computerized keyword searches in online databases, often working with a trained librarian or information expert. Keywords can be combined using the Boolean operators, “and”, “or” and sometimes “not” to narrow down or expand the search results. Once a list of articles is generated from the keyword and subject heading search, the researcher must then manually browse through each title and abstract, to determine the suitability of that article before a full-text article is obtained for the research question.

Literature reviews should be reasonably complete, and not restricted to a few journals, a few years, or a specific methodology or research design. Reviewed articles may be summarized in the form of tables, and can be further structured using organizing frameworks such as a concept matrix.

A well-conducted literature review should indicate whether the initial research questions have already been addressed in the literature, whether there are newer or more interesting research questions available, and whether the original research questions should be modified or changed in light of findings of the literature review.

The review can also provide some intuitions or potential answers to the questions of interest and/or help identify theories that have previously been used to address similar questions and may provide evidence to inform policy or decision-making. ( Bhattacherjee, 2012 ).

Read Abstract 1. Refer to Types of Literature Reviews. What type of literature review do you think this study is and why? See the Answer Key for the correct response.

Nursing : To describe evidence of international literature on the safe care of the hospitalised child after the World Alliance for Patient Safety and list contributions of the general theoretical framework of patient safety for paediatric nursing.

An integrative literature review between 2004 and 2015 using the databases PubMed, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Scopus, Web of Science and Wiley Online Library, and the descriptors Safety or Patient safety, Hospitalised child, Paediatric nursing, and Nursing care.

Thirty-two articles were analysed, most of which were from North American, with a descriptive approach. The quality of the recorded information in the medical records, the use of checklists, and the training of health workers contribute to safe care in paediatric nursing and improve the medication process and partnerships with parents.

General information available on patient safety should be incorporated in paediatric nursing care. ( Wegner, Silva, Peres, Bandeira, Frantz, Botene, & Predebon, 2017 ).

Read Abstract 2. Refer to Types of Literature Reviews. What type of lit review do you think this study is and why? See the Answer Key for the correct response.

Education : The focus of this paper centers around timing associated with early childhood education programs and interventions using meta-analytic methods. At any given assessment age, a child’s current age equals starting age, plus duration of program, plus years since program ended. Variability in assessment ages across the studies should enable everyone to identify the separate effects of all three time-related components. The project is a meta-analysis of evaluation studies of early childhood education programs conducted in the United States and its territories between 1960 and 2007. The population of interest is children enrolled in early childhood education programs between the ages of 0 and 5 and their control-group counterparts. Since the data come from a meta-analysis, the population for this study is drawn from many different studies with diverse samples. Given the preliminary nature of their analysis, the authors cannot offer conclusions at this point. ( Duncan, Leak, Li, Magnuson, Schindler, & Yoshikawa, 2011 ).

Test Yourself

See Answer Key for the correct responses.