Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.3 Drafting

Learning objectives.

- Identify drafting strategies that improve writing.

- Use drafting strategies to prepare the first draft of an essay.

Drafting is the stage of the writing process in which you develop a complete first version of a piece of writing.

Even professional writers admit that an empty page scares them because they feel they need to come up with something fresh and original every time they open a blank document on their computers. Because you have completed the first two steps in the writing process, you have already recovered from empty page syndrome. You have hours of prewriting and planning already done. You know what will go on that blank page: what you wrote in your outline.

Getting Started: Strategies For Drafting

Your objective for this portion of Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” is to draft the body paragraphs of a standard five-paragraph essay. A five-paragraph essay contains an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. If you are more comfortable starting on paper than on the computer, you can start on paper and then type it before you revise. You can also use a voice recorder to get yourself started, dictating a paragraph or two to get you thinking. In this lesson, Mariah does all her work on the computer, but you may use pen and paper or the computer to write a rough draft.

Making the Writing Process Work for You

What makes the writing process so beneficial to writers is that it encourages alternatives to standard practices while motivating you to develop your best ideas. For instance, the following approaches, done alone or in combination with others, may improve your writing and help you move forward in the writing process:

- Begin writing with the part you know the most about. You can start with the third paragraph in your outline if ideas come easily to mind. You can start with the second paragraph or the first paragraph, too. Although paragraphs may vary in length, keep in mind that short paragraphs may contain insufficient support. Readers may also think the writing is abrupt. Long paragraphs may be wordy and may lose your reader’s interest. As a guideline, try to write paragraphs longer than one sentence but shorter than the length of an entire double-spaced page.

- Write one paragraph at a time and then stop. As long as you complete the assignment on time, you may choose how many paragraphs you complete in one sitting. Pace yourself. On the other hand, try not to procrastinate. Writers should always meet their deadlines.

- Take short breaks to refresh your mind. This tip might be most useful if you are writing a multipage report or essay. Still, if you are antsy or cannot concentrate, take a break to let your mind rest. But do not let breaks extend too long. If you spend too much time away from your essay, you may have trouble starting again. You may forget key points or lose momentum. Try setting an alarm to limit your break, and when the time is up, return to your desk to write.

- Be reasonable with your goals. If you decide to take ten-minute breaks, try to stick to that goal. If you told yourself that you need more facts, then commit to finding them. Holding yourself to your own goals will create successful writing assignments.

- Keep your audience and purpose in mind as you write. These aspects of writing are just as important when you are writing a single paragraph for your essay as when you are considering the direction of the entire essay.

Of all of these considerations, keeping your purpose and your audience at the front of your mind is the most important key to writing success. If your purpose is to persuade, for example, you will present your facts and details in the most logical and convincing way you can.

Your purpose will guide your mind as you compose your sentences. Your audience will guide word choice. Are you writing for experts, for a general audience, for other college students, or for people who know very little about your topic? Keep asking yourself what your readers, with their background and experience, need to be told in order to understand your ideas. How can you best express your ideas so they are totally clear and your communication is effective?

You may want to identify your purpose and audience on an index card that you clip to your paper (or keep next to your computer). On that card, you may want to write notes to yourself—perhaps about what that audience might not know or what it needs to know—so that you will be sure to address those issues when you write. It may be a good idea to also state exactly what you want to explain to that audience, or to inform them of, or to persuade them about.

Writing at Work

Many of the documents you produce at work target a particular audience for a particular purpose. You may find that it is highly advantageous to know as much as you can about your target audience and to prepare your message to reach that audience, even if the audience is a coworker or your boss. Menu language is a common example. Descriptions like “organic romaine” and “free-range chicken” are intended to appeal to a certain type of customer though perhaps not to the same customer who craves a thick steak. Similarly, mail-order companies research the demographics of the people who buy their merchandise. Successful vendors customize product descriptions in catalogs to appeal to their buyers’ tastes. For example, the product descriptions in a skateboarder catalog will differ from the descriptions in a clothing catalog for mature adults.

Using the topic for the essay that you outlined in Section 8.2 “Outlining” , describe your purpose and your audience as specifically as you can. Use your own sheet of paper to record your responses. Then keep these responses near you during future stages of the writing process.

My purpose: ____________________________________________

____________________________________________

My audience: ____________________________________________

Setting Goals for Your First Draft

A draft is a complete version of a piece of writing, but it is not the final version. The step in the writing process after drafting, as you may remember, is revising. During revising, you will have the opportunity to make changes to your first draft before you put the finishing touches on it during the editing and proofreading stage. A first draft gives you a working version that you can later improve.

Workplace writing in certain environments is done by teams of writers who collaborate on the planning, writing, and revising of documents, such as long reports, technical manuals, and the results of scientific research. Collaborators do not need to be in the same room, the same building, or even the same city. Many collaborations are conducted over the Internet.

In a perfect collaboration, each contributor has the right to add, edit, and delete text. Strong communication skills, in addition to strong writing skills, are important in this kind of writing situation because disagreements over style, content, process, emphasis, and other issues may arise.

The collaborative software, or document management systems, that groups use to work on common projects is sometimes called groupware or workgroup support systems.

The reviewing tool on some word-processing programs also gives you access to a collaborative tool that many smaller workgroups use when they exchange documents. You can also use it to leave comments to yourself.

If you invest some time now to investigate how the reviewing tool in your word processor works, you will be able to use it with confidence during the revision stage of the writing process. Then, when you start to revise, set your reviewing tool to track any changes you make, so you will be able to tinker with text and commit only those final changes you want to keep.

Discovering the Basic Elements of a First Draft

If you have been using the information in this chapter step by step to help you develop an assignment, you already have both a formal topic outline and a formal sentence outline to direct your writing. Knowing what a first draft looks like will help you make the creative leap from the outline to the first draft. A first draft should include the following elements:

- An introduction that piques the audience’s interest, tells what the essay is about, and motivates readers to keep reading.

- A thesis statement that presents the main point, or controlling idea, of the entire piece of writing.

- A topic sentence in each paragraph that states the main idea of the paragraph and implies how that main idea connects to the thesis statement.

- Supporting sentences in each paragraph that develop or explain the topic sentence. These can be specific facts, examples, anecdotes, or other details that elaborate on the topic sentence.

- A conclusion that reinforces the thesis statement and leaves the audience with a feeling of completion.

These elements follow the standard five-paragraph essay format, which you probably first encountered in high school. This basic format is valid for most essays you will write in college, even much longer ones. For now, however, Mariah focuses on writing the three body paragraphs from her outline. Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” covers writing introductions and conclusions, and you will read Mariah’s introduction and conclusion in Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” .

The Role of Topic Sentences

Topic sentences make the structure of a text and the writer’s basic arguments easy to locate and comprehend. In college writing, using a topic sentence in each paragraph of the essay is the standard rule. However, the topic sentence does not always have to be the first sentence in your paragraph even if it the first item in your formal outline.

When you begin to draft your paragraphs, you should follow your outline fairly closely. After all, you spent valuable time developing those ideas. However, as you begin to express your ideas in complete sentences, it might strike you that the topic sentence might work better at the end of the paragraph or in the middle. Try it. Writing a draft, by its nature, is a good time for experimentation.

The topic sentence can be the first, middle, or final sentence in a paragraph. The assignment’s audience and purpose will often determine where a topic sentence belongs. When the purpose of the assignment is to persuade, for example, the topic sentence should be the first sentence in a paragraph. In a persuasive essay, the writer’s point of view should be clearly expressed at the beginning of each paragraph.

Choosing where to position the topic sentence depends not only on your audience and purpose but also on the essay’s arrangement, or order. When you organize information according to order of importance, the topic sentence may be the final sentence in a paragraph. All the supporting sentences build up to the topic sentence. Chronological order may also position the topic sentence as the final sentence because the controlling idea of the paragraph may make the most sense at the end of a sequence.

When you organize information according to spatial order, a topic sentence may appear as the middle sentence in a paragraph. An essay arranged by spatial order often contains paragraphs that begin with descriptions. A reader may first need a visual in his or her mind before understanding the development of the paragraph. When the topic sentence is in the middle, it unites the details that come before it with the ones that come after it.

As you read critically throughout the writing process, keep topic sentences in mind. You may discover topic sentences that are not always located at the beginning of a paragraph. For example, fiction writers customarily use topic ideas, either expressed or implied, to move readers through their texts. In nonfiction writing, such as popular magazines, topic sentences are often used when the author thinks it is appropriate (based on the audience and the purpose, of course). A single topic sentence might even control the development of a number of paragraphs. For more information on topic sentences, please see Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content” .

Developing topic sentences and thinking about their placement in a paragraph will prepare you to write the rest of the paragraph.

The paragraph is the main structural component of an essay as well as other forms of writing. Each paragraph of an essay adds another related main idea to support the writer’s thesis, or controlling idea. Each related main idea is supported and developed with facts, examples, and other details that explain it. By exploring and refining one main idea at a time, writers build a strong case for their thesis.

Paragraph Length

How long should a paragraph be?

One answer to this important question may be “long enough”—long enough for you to address your points and explain your main idea. To grab attention or to present succinct supporting ideas, a paragraph can be fairly short and consist of two to three sentences. A paragraph in a complex essay about some abstract point in philosophy or archaeology can be three-quarters of a page or more in length. As long as the writer maintains close focus on the topic and does not ramble, a long paragraph is acceptable in college-level writing. In general, try to keep the paragraphs longer than one sentence but shorter than one full page of double-spaced text.

Journalistic style often calls for brief two- or three-sentence paragraphs because of how people read the news, both online and in print. Blogs and other online information sources often adopt this paragraphing style, too. Readers often skim the first paragraphs of a great many articles before settling on the handful of stories they want to read in detail.

You may find that a particular paragraph you write may be longer than one that will hold your audience’s interest. In such cases, you should divide the paragraph into two or more shorter paragraphs, adding a topic statement or some kind of transitional word or phrase at the start of the new paragraph. Transition words or phrases show the connection between the two ideas.

In all cases, however, be guided by what you instructor wants and expects to find in your draft. Many instructors will expect you to develop a mature college-level style as you progress through the semester’s assignments.

To build your sense of appropriate paragraph length, use the Internet to find examples of the following items. Copy them into a file, identify your sources, and present them to your instructor with your annotations, or notes.

- A news article written in short paragraphs. Take notes on, or annotate, your selection with your observations about the effect of combining paragraphs that develop the same topic idea. Explain how effective those paragraphs would be.

- A long paragraph from a scholarly work that you identify through an academic search engine. Annotate it with your observations about the author’s paragraphing style.

Starting Your First Draft

Now we are finally ready to look over Mariah’s shoulder as she begins to write her essay about digital technology and the confusing choices that consumers face. As she does, you should have in front of you your outline, with its thesis statement and topic sentences, and the notes you wrote earlier in this lesson on your purpose and audience. Reviewing these will put both you and Mariah in the proper mind-set to start.

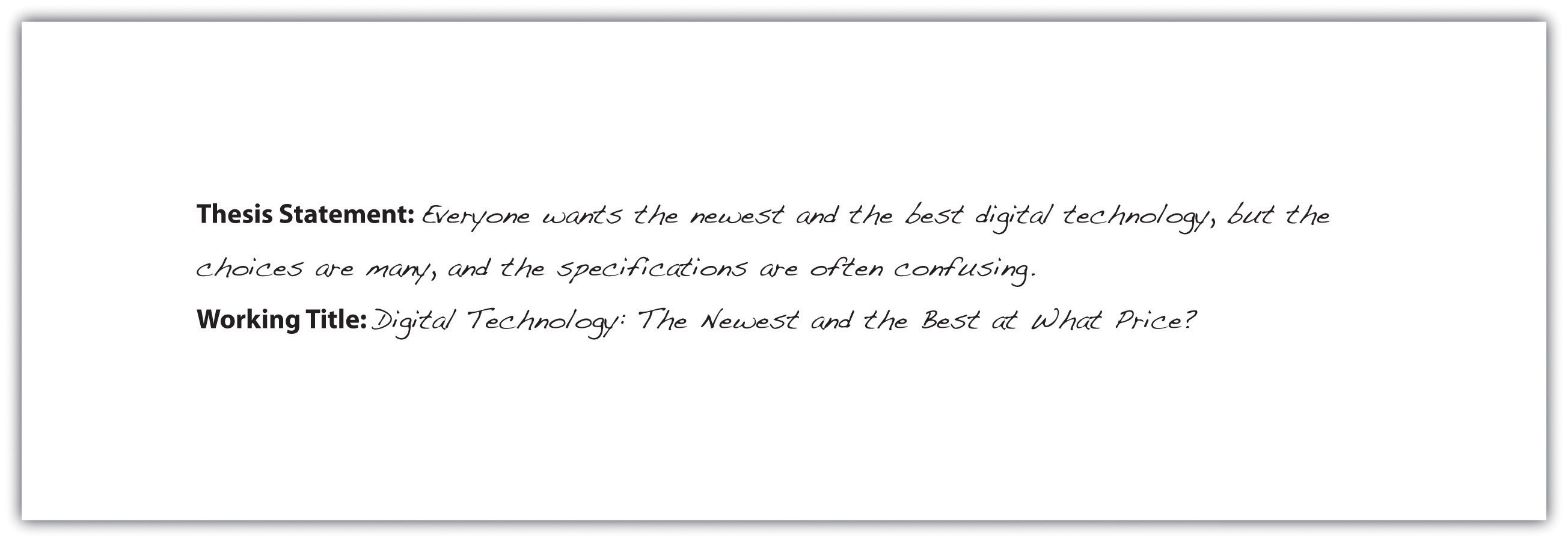

The following is Mariah’s thesis statement.

Here are the notes that Mariah wrote to herself to characterize her purpose and audience.

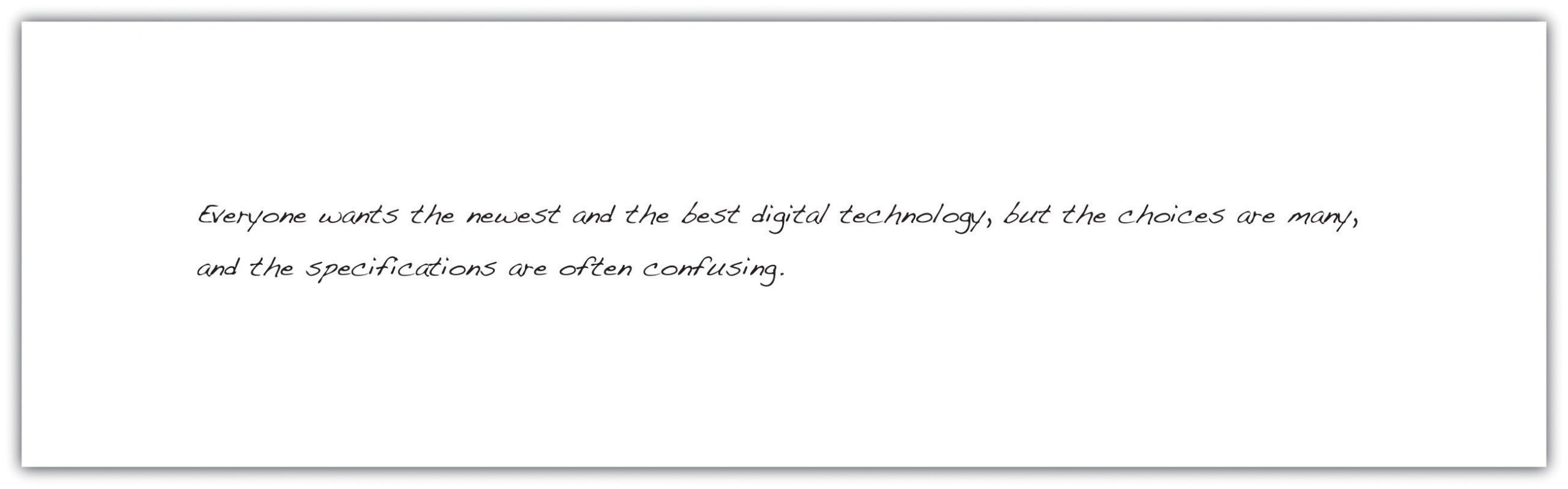

Mariah chose to begin by writing a quick introduction based on her thesis statement. She knew that she would want to improve her introduction significantly when she revised. Right now, she just wanted to give herself a starting point. You will read her introduction again in Section 8.4 “Revising and Editing” when she revises it.

Remember Mariah’s other options. She could have started directly with any of the body paragraphs.

You will learn more about writing attention-getting introductions and effective conclusions in Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” .

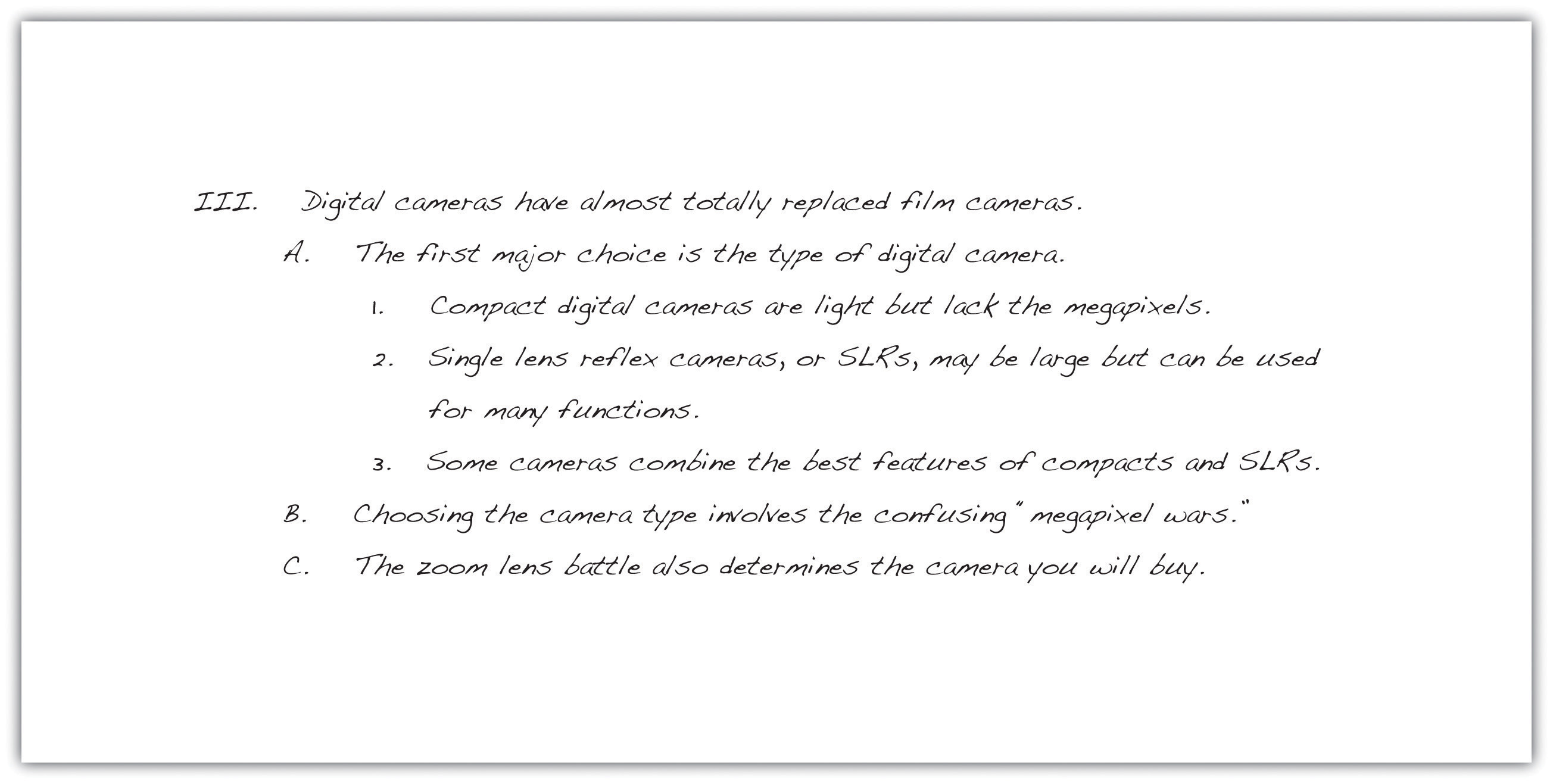

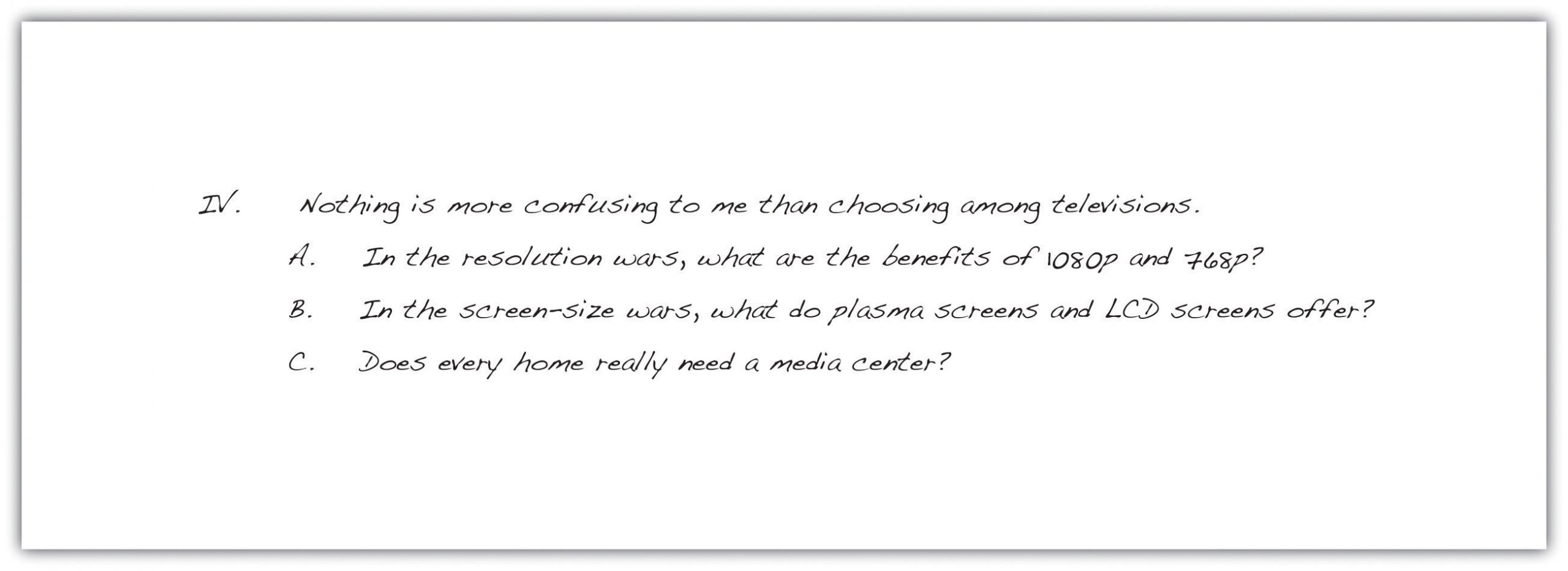

With her thesis statement and her purpose and audience notes in front of her, Mariah then looked at her sentence outline. She chose to use that outline because it includes the topic sentences. The following is the portion of her outline for the first body paragraph. The roman numeral II identifies the topic sentence for the paragraph, capital letters indicate supporting details, and arabic numerals label subpoints.

Mariah then began to expand the ideas in her outline into a paragraph. Notice how the outline helped her guarantee that all her sentences in the body of the paragraph develop the topic sentence.

If you write your first draft on the computer, consider creating a new file folder for each course with a set of subfolders inside the course folders for each assignment you are given. Label the folders clearly with the course names, and label each assignment folder and word processing document with a title that you will easily recognize. The assignment name is a good choice for the document. Then use that subfolder to store all the drafts you create. When you start each new draft, do not just write over the last one. Instead, save the draft with a new tag after the title—draft 1, draft 2, and so on—so that you will have a complete history of drafts in case your instructor wishes you to submit them.

In your documents, observe any formatting requirements—for margins, headers, placement of page numbers, and other layout matters—that your instructor requires.

Study how Mariah made the transition from her sentence outline to her first draft. First, copy her outline onto your own sheet of paper. Leave a few spaces between each part of the outline. Then copy sentences from Mariah’s paragraph to align each sentence with its corresponding entry in her outline.

Continuing the First Draft

Mariah continued writing her essay, moving to the second and third body paragraphs. She had supporting details but no numbered subpoints in her outline, so she had to consult her prewriting notes for specific information to include.

If you decide to take a break between finishing your first body paragraph and starting the next one, do not start writing immediately when you return to your work. Put yourself back in context and in the mood by rereading what you have already written. This is what Mariah did. If she had stopped writing in the middle of writing the paragraph, she could have jotted down some quick notes to herself about what she would write next.

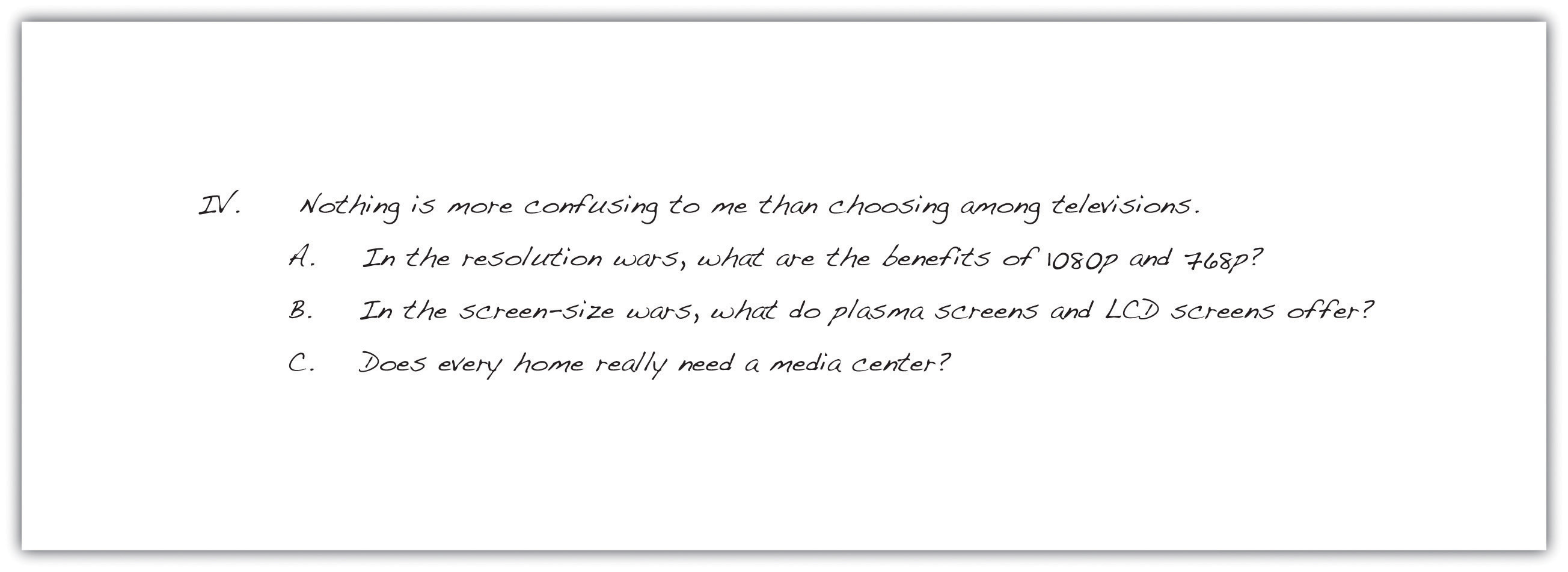

Preceding each body paragraph that Mariah wrote is the appropriate section of her sentence outline. Notice how she expanded roman numeral III from her outline into a first draft of the second body paragraph. As you read, ask yourself how closely she stayed on purpose and how well she paid attention to the needs of her audience.

Mariah then began her third and final body paragraph using roman numeral IV from her outline.

Reread body paragraphs two and three of the essay that Mariah is writing. Then answer the questions on your own sheet of paper.

- In body paragraph two, Mariah decided to develop her paragraph as a nonfiction narrative. Do you agree with her decision? Explain. How else could she have chosen to develop the paragraph? Why is that better?

- Compare the writing styles of paragraphs two and three. What evidence do you have that Mariah was getting tired or running out of steam? What advice would you give her? Why?

- Choose one of these two body paragraphs. Write a version of your own that you think better fits Mariah’s audience and purpose.

Writing a Title

A writer’s best choice for a title is one that alludes to the main point of the entire essay. Like the headline in a newspaper or the big, bold title in a magazine, an essay’s title gives the audience a first peek at the content. If readers like the title, they are likely to keep reading.

Following her outline carefully, Mariah crafted each paragraph of her essay. Moving step by step in the writing process, Mariah finished the draft and even included a brief concluding paragraph (you will read her conclusion in Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” ). She then decided, as the final touch for her writing session, to add an engaging title.

Writing Your Own First Draft

Now you may begin your own first draft, if you have not already done so. Follow the suggestions and the guidelines presented in this section.

Key Takeaways

- Make the writing process work for you. Use any and all of the strategies that help you move forward in the writing process.

- Always be aware of your purpose for writing and the needs of your audience. Cater to those needs in every sensible way.

- Remember to include all the key structural parts of an essay: a thesis statement that is part of your introductory paragraph, three or more body paragraphs as described in your outline, and a concluding paragraph. Then add an engaging title to draw in readers.

- Write paragraphs of an appropriate length for your writing assignment. Paragraphs in college-level writing can be a page long, as long as they cover the main topics in your outline.

- Use your topic outline or your sentence outline to guide the development of your paragraphs and the elaboration of your ideas. Each main idea, indicated by a roman numeral in your outline, becomes the topic of a new paragraph. Develop it with the supporting details and the subpoints of those details that you included in your outline.

- Generally speaking, write your introduction and conclusion last, after you have fleshed out the body paragraphs.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to ChatBot Assistant

- Academic Writing

- Research Writing

- Critical Reading and Writing

- Punctuation

- Writing Exercises

- ELL/ESL Resources

Building the Essay Draft

Building a strong essay draft requires going through a logical progression of stages:, explanation.

Development options

Linking paragraphs

Introductions

Conclusions.

Revising and proofreading the draft

Hints for revising and proofreading

Tip: After you have completed the body of your paper, you can decide what you want to say in your introduction and in your conclusion.

Once you know what you want to talk about and you have written your thesis statement, you are ready to build the body of your essay.

The thesis statement will usually be followed by

- the body of the paper

- the paragraphs that develop the thesis by explaining your ideas by backing them up

- examples or evidence

Tip: The "examples or evidence" stage is the most important part of the paper, because you are giving your reader a clear idea of what you think and why you think it.

Development Options

- For each reason you have to support your thesis, remember to state your point clearly and explain it.

Tip: Read your thesis sentence over and ask yourself what questions a reader might ask about it. Then answer those questions, explaining and giving examples or evidence.

Show how one thing is similar to another, and then how the two are different, emphasizing the side that seems more important to you. For example, if your thesis states, "Jazz is a serious art form," you might compare and contrast a jazz composition to a classical one.

Show your reader what the opposition thinks (reasons why some people do not agree with your thesis), and then refute those reasons (show why they are wrong). On the other hand, if you feel that the opposition isn't entirely wrong, you may say so, (concede), but then explain why your thesis is still the right opinion.

- Think about the order in which you have made your points. Why have you presented a certain reason that develops your thesis first, another second? If you can't see any particular value in presenting your points in the order you have, reconsider it until you either decide why the order you have is best, or change it to one that makes more sense to you.

- Does each paragraph develop my thesis?

- Have I done all the development I wish had been done?

- Am I still satisfied with my working thesis, or have I developed my body in ways that mean I must adjust my thesis to fit what I have learned, what I believe, and what I have actually discussed?

Linking Paragraphs

It is important to link your paragraphs together, giving your readers cues so that they see the relationship between one idea and the next, and how these ideas develop your thesis.

Your goal is a smooth transition from paragraph A to paragraph B, which explains why cue words that link paragraphs are often called "transitions."

Tip: Your link between paragraphs may not be one word, but several, or even a whole sentence.

Here are some ways of linking paragraphs:

- To show simply that another idea is coming, use words such as "also," "moreover," or "in addition."

- To show that the next idea is the logical result of the previous one, use words such as "therefore," "consequently," "thus," or "as a result."

- To show that the next idea seems to go against the previous one, or is not its logical result, use words such as "however," "nevertheless," or "still."

- To show you've come to your strongest point, use words such as "most importantly."

- To show you've come to a change in topic, use words such as "on the other hand."

- To show you've come to your final point, use words such as "finally."

After you have come up with a thesis and developed it in the body of your paper, you can decide how to introduce your ideas to your reader.

The goals of an introduction are to

- Get your reader's attention/arouse your reader's curiosity.

- Provide any necessary background information before you state your thesis (often the last sentence of the introductory paragraph).

- Establish why you are writing the paper.

Tip: You already know why you are writing, and who your reader is; now present that reason for writing to that reader.

Hints for writing your introduction:

- Use the Ws of journalism (who, what, when, where, why) to decide what information to give. (Remember that a history teacher doesn't need to be told "George Washington was the first president of the United States." Keep your reader in mind.)

- Add another "W": Why (why is this paper worth reading)? The answer could be that your topic is new, controversial, or very important.

- Catch your reader by surprise by starting with a description or narrative that doesn't hint at what your thesis will be. For example, a paper could start, "It is less than a 32nd of an inch long, but it can kill an adult human," to begin a paper about eliminating malaria-carrying mosquitoes.

There can be many different conclusions to the same paper (just as there can be many introductions), depending on who your readers are and where you want to direct them (follow-up you expect of them after they finish your paper). Therefore, restating your thesis and summarizing the main points of your body should not be all that your conclusion does. In fact, most weak conclusions are merely restatements of the thesis and summaries of the body without guiding the reader toward thinking about the implications of the thesis.

Here are some options for writing a strong conclusion:

Make a prediction about the future. You convinced the reader that thermal energy is terrific, but do you think it will become the standard energy source? When?

Give specific advice. If your readers now understand that multicultural education has great advantages, or disadvantages, or both, whatever your opinion might be, what should they do? Whom should they contact?

Put your topic in a larger context. Once you have proven that physical education should be part of every school's curriculum, perhaps readers should consider other "frill" courses which are actually essential.

Tip: Just as a conclusion should not be just a restatement of your thesis and summary of your body, it also should not be an entirely new topic, a door opened that you barely lead your reader through and leave them there lost. Just as in finding your topic and in forming your thesis, the safe and sane rule in writing a conclusion is this: neither too little nor too much.

Revising and Proofreading the Draft

Writing is only half the job of writing..

The writing process begins even before you put pen to paper, when you think about your topic. And, once you finish actually writing, the process continues. What you have written is not the finished essay, but a first draft, and you must go over many times to improve it--a second draft, a third draft, and so on until you have as many as necessary to do the job right. Your final draft, edited and proofread, is your essay, ready for your reader's eyes.

A revision is a "re-vision" of your essay--how you see things now, deciding whether your introduction, thesis, body, and conclusion really express your own vision. Revision is global, taking another look at what ideas you have included in your paper and how they are arranged.

Proofreading

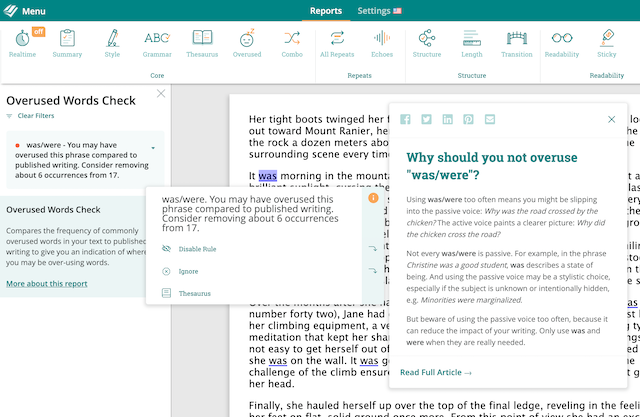

Proofreading is checking over a draft to make sure that everything is complete and correct as far as spelling, grammar, sentence structure, punctuation, and other such matters go. It's a necessary, if somewhat tedious and tricky, job one that a friend or computer Spellcheck can help you perform. Proofreading is polishing, one spot at a time.

Tip: Revision should come before proofreading: why polish what you might be changing anyway?

Hints for revising and proofreading:

- Leave some time--an hour, a day, several day--between writing and revising. You need some distance to switch from writer to editor, some distance between your initial vision and your re-vision.

- Double-check your writing assignment to be sure you haven't gone off course . It is all right if you've shifted from your original plan, if you know why and are happier with this direction. Make sure that you are actually following your mentor's assignment.

- Read aloud slowly . You need to get your eye and your ear to work together. At any point that something seems awkward, read it over again. If you're not sure what's wrong--or even if something is wrong--make a notation in the margin and come back to it later. Watch out for "padding;" tighten your sentences to eliminate excess words that dilute your ideas.

- Be on the lookout for points that seem vague or incomplete ; these could present opportunities for rethinking, clarifying, and further developing an idea.

- Get to know what your particular quirks are as a writer. Do you give examples without explaining them, or forget links between paragraphs? Leave time for an extra rereading to look for any weak points.

- Get someone else into the act. Have others read your draft, or read it to them. Invite questions and ask questions yourself, to see if your points are clear and well-developed. Remember, though, that some well-meaning readers can be too easy (or too hard) on a piece of writing.

Tip: Never change anything unless you are convinced that it should be changed .

- Keep tools at hand, such as a dictionary, a thesaurus, and a writing handbook.

- While you're using word processing, remember that computers are wonderful resources for editing and revising.

- When you feel you've done everything you can, first by revising and then by proofreading, and have a nice clean, final draft, put it aside and return later to re-see the whole essay. There may be some last minute fine-tuning that can make all the difference.

Don't forget--if you would like help with at this point in your assignment or any other type of writing assignment, learning coaches are available to assist you. Please contact Academic Support by emailing [email protected] ; calling 1-800-847-3000, ext 3008; or calling the main number of the location in your region to schedule an appointment. Use this resource to find more information about Academic Support .

Don't forget--if you would like help with at this point in your assignment or any other type of writing assignment, learning coaches are available to assist you. Please contact Academic Support by emailing [email protected] ; calling 1-800-847-3000, ext 3008; or calling the main number of the location in your region (click here for more information) to schedule an appointment.

Need Assistance?

If you would like assistance with any type of writing assignment, learning coaches are available to assist you. Please contact Academic Support by emailing [email protected].

Questions or feedback about SUNY Empire's Writing Support?

Contact us at [email protected] .

Smart Cookies

They're not just in our classes – they help power our website. Cookies and similar tools allow us to better understand the experience of our visitors. By continuing to use this website, you consent to SUNY Empire State University's usage of cookies and similar technologies in accordance with the university's Privacy Notice and Cookies Policy .

The Writing Process

Making expository writing less stressful, more efficient, and more enlightening

Step 3: Draft

“It is an unnecessary burden to try to think of words and also worry at the same time whether they’re the right words.” — Peter Elbow

There are many reasons that people (including native speakers) find writing difficult, but one of the biggest is that when we write our papers, we are often trying to do two things at once:

- To say them in the best possible way (i.e., perfectly), with correct grammar and elegant wording

These are two complex but very different mental processes. No wonder writing can seem difficult. Add to this a third obstacle ,

- To write in a foreign language

and you might think it’s a wonder that you can write at all!

There is a simple solution, however, namley to separate these processes into distinct steps. Namely, when writing your first draft, just focus on getting the ideas roughly into sentences . Don’t worry too much about grammar, spelling, or even ideal vocabulary. You can not worry for three reasons :

- If you are writing expository papers, your English is probably now at a fairly high level, so it will actually be difficult for you to make too many mistakes;

- You have already outlined your ideas, working with the language and finding much accurate vocabulary there, meaning that you’re not working from scratch but rather building on something you are already familiar with . Now you’re just putting it in sentence and paragraph form;

And the third and biggest reason:

- The term “Draft” (instead of “Write”) implicitly contains the awareness that you will have other drafts in the future , meaning that you know that this one will be revised and edited in later steps.

Just let the ideas flow into sentences as though you are pouring concrete into wooden frame; you’ll smooth it out later.

Thus when drafting, simpy do the following:

- Either print out your detailed outline and have it in front of you, or have it on the left side of your computer screen and your draft document on the right.

- Do write complete sentences and paragraphs, and try moderately to use proper grammar, accurate wording, and transition words to link your ideas as necessary.

- However, almost as in freewriting, don’t let yourself get stuck . You may pause for a few seconds, but don’t labor over sentences. Just get them down and move on.

- Even without worrying excessively about grammar, putting your ideas in sentence form will not always be easy. Ideas can be complex and difficult to express, and even native English speakers must struggle sometimes to say (or even know!) exactly what they mean, so don’t expect yourself to be able to do it the first time.

- Let yourself write freely and feel the satisfaction of 1) getting a draft done, and then 2) crafting it to say what you want to say the way you want say it.

Click to watch a short video modeling how to write a draft.

- Peterborough

Drafting the English Essay

- Creating an outline

- The use of "I" (first-person)

- Historical present

- Drafting body paragraphs

- The introduction

- The conclusion

Creating an Outline

Making an outline before you start to write has the same advantage as writing down your thesis as soon as you have one. It forces you to think about the best possible order for what you want to say and to think through your line of thought before you have to write sentences and paragraphs.

Remember that an essay and its outline do not have to be structured into five paragraphs. Think about major points, sections or parts of your essay, rather than paragraphs. The number of sections you have will depend on what you have to say and how you think your thesis needs to be supported. It is possible to structure an essay around two major points, each divided into sub-points. Or you may structure an essay around four, five or six points, depending on the essay's length. An essay under 1500 words may fall naturally into three sections, but let the number come from what you have to say rather than striving for the magic three.

Creating an outline also helps you avoid the temptation of organizing your essay by following the plot line of the text you are writing about and simply retelling the story with a few of your own comments thrown in. If you conscientiously make an outline that is ordered to best support your thesis, which is there in print before your eyes, your essay’s organization will be based on supporting your argument not on the text’s plotline.

Read more on organizing your essay

Writing the Draft

If you have followed good essay-writing practice, which includes developing a narrowed topic and analytical thesis, reading closely and taking careful notes, and creating an organized outline, you will find that writing your essay is much less difficult than if you simply sit down and plunge in with a vague topic in mind.

Always keep your reader in mind when you write. Work to convince this reader that your argument is valid and has merit. To do this, you must write clearly. The best writing is the product of drafting and revising.

As you write your rough draft, your ideas will develop, so it is helpful to accept the messy process of drafting. Review your sections as you write, but leave most of the revision for when you have a completed first draft. When you revise, you can refine your ideas by making your language more specific and direct, by developing your explanation of a quotation, and by explaining the connections between your ideas. Remember that your goal is clear expression; use a formal tone, avoid slang and colloquial terms, and be precise in your language.

Stylistic Notes for Writing the English Essay

The use of "i".

The judicious use of "I" in English essays is generally accepted. (You may run into a professor who doesn't want you to and says so, and, in that case, don't). The key is to not to overuse "I". When writing your draft, you may find it helpful to get your thoughts flowing by writing "I think that..." but when you revise, you will find that those three words can be eliminated from the sentences they begin.

For example:

I think that these poems also share a rather detached, unemotional, matter-of-fact acceptance of death.

Revised: These poems share a rather detached, unemotional, matter-of-fact acceptance of death.

I think death, dying, and the moments that precede dying preoccupy Dickinson.

Revised: Death, dying, and the moments the precede dying preoccupy Dickinson.

The Historical Present

Instructors generally agree that students should use the the present tense, which is known as the historical present, when describing events in a work of literature (or a film) or when discussing what authors or scholars say about a topic or issue, even when the work of literature is from the past or uses the past tense itself, or the authors and scholars are dead.

Examples of historical present:

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream , Bottom is a uniformly comedic figure.

Kyi argues that “democracy is the political system through which an empowerment of the people occurs.”

It is considered more accurate to use the present tense in these circumstances because the arguments put forward by scholars, and the characters presented and scenes depicted by novelists, poets, and dramatists continue to live in the present whenever anyone reads them. An added benefit is that many find the use of the historical present tense makes for a more lively style and a stronger voice.

Drafting Body Paragraphs

The body of the essay will be made up of the claims or points you are making, supported by evidence from the primary source, the work in question, and perhaps some secondary sources. Your supporting evidence may be quotations of words or phrases from the text, as well as details about character, setting, plot, syntax, diction, images and anything else you have found in the work that is relevant to your argument.

Writing successful paragraphs

You may find yourself quoting often, and that is fine. The words from the text are, after all, the support for the argument you are making, and they show that your ideas came from somewhere and are grounded in the text. But try to keep your quotations as short and pertinent as possible. Use quotations effectively to support your interpretation or arguments; be sure to explain the quotation: what does it illustrates and how?

Effectively integrating evidence

Make sure you don't use or quote words whose definition or meaning you are not sure about. As a student of English literature, you should make regular use of a good dictionary; many academics recommend the Oxford English Dictionary . Not knowing what a word means or misunderstanding how it is used can undermine a whole argument. When you read and write about authors from previous centuries, you will often have to familiarize yourself with new words. To write good English essays, you must take the time to do this.

Sample Body Paragraph

This body paragraph is a sample only. Its content is not to be reproduced in whole or part. Use of the ideas or words in this essay is an act of plagiarism, which is subject to academic integrity policy at Trent University and other academic institutions.

“Because I could not stop for Death” describes the process of dying right up to and past the moment of death, in the first person. This process is described symbolically. The speaker, walking along the road of life is picked up and given a carriage ride out of town to her destination, the graveyard and death. The speaker, looking back, says that she “could not stop for Death – / [so] He kindly stopped for” her (1-2). Dickinson personifies death as a “kindly” (2) masculine being with “civility” (6). As the two “slowly dr[i]ve” (5) down the road of life, the speaker observes life in its simplicity: the “School,” (9), “the Fields of Gazing Grain” (11), and the “Setting Sun” (12), and realizes that this road out of town is the road out of life. The road’s ending at “a House that seemed / A Swelling of the Ground” (17-18) is a life’s ending at death, “Eternity” (24). Once in the House that is the speaker’s grave, that is, after death, the speaker remains conscious. Her death is not experienced as a loss of consciousness, a sleep or oblivion. Her sense of time does change though:

Since then – 'tis Centuries – and yet Feels shorter than the Day I first surmised the Horses' Heads Were toward Eternity – (20-24)

It has become difficult for the speaker to tell the difference between a century and a day. But she knows it has been “Centuries” since then, so the implication is that her consciousness has lived on in an eternal afterlife.

What works in the sample paragraph?

- The topic sentence makes a clear claim that the rest of the paragraph develops through details, quotations and analysis.

- The quotation is followed by the writer’s analysis of the quoted words and argument about their implication. This is the best way to use textual evidence.

The Introduction

Often, the introduction is the hardest part to write. Here you make your first impression, introduce the topic, provide background information, define key terms perhaps, and, most important, present your thesis, upon which the entire essay hangs. Many people find it easiest to write the introduction last or to write a very rough introduction that they change significantly once the draft is complete.

Strategies for writing the introduction

Sample Introduction

This introductory paragraph is a sample only. Its content is not to be reproduced in whole or part. Use of the ideas or words in this essay is an act of plagiarism, which is subject to academic integrity policy at Trent University and other academic institutions.

Emily Dickinson was captivated by the riddle of death, and several of her poems deal with it in different ways. There are many poems that describe, in the first person, the process of dying right up to and including the moment of death, often recalled from a vantage point after death in some sort of afterlife. As well, several poems speculate more generally about what lies beyond the visible world our senses perceive in life. This essay examines four of Dickinson’s poems that are about dying and death and one that is more speculative. Two are straightforwardly about dying, while the other two present dying symbolically, but taken together they show many similarities. Death is experienced matter-of-factly and without fear and with a full consciousness that registers details and describes them clearly. All the poems examined hint at an afterlife which is not described in traditionally Christian terms but which is not contradictory to Christian belief either. Yet death remains a riddle. While one poem may emphasize an afterlife of peace, silence and anchors at rest, others only hint at an ongoing consciousness, and one both asserts that something beyond life exists while also saying that belief is really only a narcotic that cannot completely still the pain of doubt. Dying, the moment of death, and what comes after preoccupy Dickinson: in these poems, death and eternity both “beckon” and “baffle” (Dickinson, “This World is not Conclusion” 5).

What works in this sample introduction?

- This essay has a good, narrowed, focused topic.

- The introduction does not include a general statement about life or poetry. The essay is about five poems by Dickinson, and right from the beginning, its focus is on that.

- The thesis of the essay is one sentence, but it may be more. Note that this thesis statement does not list supporting points; a good thesis statement provides the organizing principle of the essay, and the essay writer has decided to let the supporting points appear throughout the body of the essay.

The Conclusion

An effective conclusion unifies the arguments in your essay and explains the broader meaning or significance of your analysis. It is best to think of the conclusion as an opportunity to synthesize your ideas, not just summarize them. It is also your chance to explain the larger significance of your argument: if your reader now agrees with your thesis, what do they understand about the theme, the text, or the author?

Strategies for writing the conclusion

Sample Conclusion

This concluding paragraph is a sample only. Its content is not to be reproduced in whole or part. Use of the ideas or words in this essay is an act of plagiarism, which is subject to academic integrity policy at Trent University and other academic institutions.

In many ways, “On this wondrous sea” sums up the attitude toward death and eternity seen in all the poems examined. Death is experienced without fear, and life is shown as leading up to death and eternity. What exactly this eternity is like is only hinted at in most of these poems. So, what is beyond continues to “baffle,” but none of the poems present death as extinction with nothing beyond; rather what is beyond “beckons.” Death and eternity are something known, a grave that is a house, a consciousness living on, a shore to which we come “at last” after a life both stormy and “wondrous.”

What works in this sample conclusion?

- This paragraph does not just repeat the introduction. It pulls together the main ideas contained in the entire essay to try to point out their larger significance. Rather than a point-by-point list, it is a summary of what it all means taken together.

- Understanding The English Essay

- Developing a Topic and Thesis for an English Essay

- Using Secondary Sources in an English Essay

- Glossary of Common Formal Elements of Literature

- Documenting Sources in MLA Style (Modern Languages Association)

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Drafting is the stage of the writing process in which you put all of your prewriting and organizing ideas into sentences and paragraphs. The aim in drafting at first should be to write the bulk of the essay in a rough form, without worrying much about revisions and edits (which are later steps in the writing process).

The point of prewriting and organizing was to make this stage of drafting more manageable. If you take prewriting and organizing seriously, you already have notes and plan about what you need to draft. If you failed to prewrite and organize, you might be facing the terror of the blank page, which can tempt writers into trying to construct a final draft from nothing–a very bad idea. So take prewriting and organizing seriously to help make this stage of the writing process as effective as possible.

Making the Writing Process Work for You

What makes the writing process so beneficial to writers is that it encourages alternatives to standard practices while motivating you to develop your best ideas. For instance, the following approaches, done alone or in combination with others, may improve your writing and help you move forward in the writing process:

- Start with the body paragraphs. A common error is to start drafting an essay at the introduction since that’s the first paragraph in a final draft, but you cannot effectively introduce something you do not yet know. You can’t introduce someone at a social gathering if you have no idea who that person is, and you can’t effectively introduce body paragraphs that you haven’t drafted yet. So draft several body paragraphs before going back and creating an introduction that discusses them.

- Begin writing with the part you know the most about. You can start with the third paragraph in your outline if ideas come easily to mind. You can start with the second paragraph or the first paragraph, too. Although paragraphs may vary in length, keep in mind that short paragraphs may contain insufficient support. Readers may also think the writing is abrupt. Long paragraphs may be wordy and may lose your reader’s interest. As a guideline, try to write paragraphs longer than one sentence but shorter than the length of an entire double-spaced page.

- Write one paragraph at a time and then stop. As long as you complete the assignment on time, you may choose how many paragraphs you complete in one sitting. Pace yourself. On the other hand, try not to procrastinate. Writers should always meet their deadlines.

- Take short breaks to refresh your mind. This tip might be most useful if you are writing a multi-page report or essay. Still, if you are antsy or cannot concentrate, take a break to let your mind rest. But do not let breaks extend too long. If you spend too much time away from your essay, you may have trouble starting again. You may forget key points or lose momentum. Try setting an alarm to limit your break, and when the time is up, return to your desk to write.

- Be reasonable with your goals. If you decide to take ten-minute breaks, try to stick to that goal. If you told yourself that you need more facts, then commit to finding them. Holding yourself to your own goals will create successful writing assignments.

- Keep your audience and purpose in mind as you write. These aspects of writing are just as important when you are writing a single paragraph for your essay as when you are considering the direction of the entire essay.

Of all of these considerations, keeping your purpose and your audience at the front of your mind is the most important key to writing success.

Your purpose will guide your mind as you compose your sentences. Your audience will guide word choice. Are you writing for experts, for a general audience, for other college students, or for people who know very little about your topic? Keep asking yourself what your readers, with their background and experience, need to be told in order to understand your ideas. How can you best express your ideas so they are totally clear and your communication is effective?

Using a subject of your choosing (such as one you have outlined in previous exercises), describe your purpose and your audience as specifically as you can. Keep these responses near you during future stages of the writing process.

My purpose: ____________________________________________

____________________________________________

My audience: ____________________________________________

The Basic Elements of a First Draft

If you have been using the information in this chapter step by step to help you develop an assignment, you already have both a formal topic outline and a formal sentence outline to direct your writing. Knowing what a first draft looks like will help you make the creative leap from the outline to the first draft. A first draft should include the following elements:

- An introduction that clearly identifies the subject, the thesis, and the main ideas to come (in the order that they will appear).

- A thesis statement that presents the main claim of the entire piece of writing.

- A topic sentence in each paragraph that states the main point of the paragraph and implies how that main point connects to the thesis statement.

- Supporting sentences in each paragraph that develop or explain the topic sentence. These can be reasons, specific examples, explanations, comparisons, facts, or other strategies that help support the main points and the thesis.

- A conclusion that emphasizes the most important ideas and interpretations.

See the chapter Paragraphs for information on topic sentences and other key parts of a paragraph. See the chapter Essays for more information on thesis statements and other key parts of an essay.

Examples of Starting a Draft

Now we are finally ready to look over Mariah’s shoulder as she begins to write her essay about digital technology and the confusing choices that consumers face. As she does, you should have in front of you your outline, with its thesis statement and topic sentences, and the notes you wrote earlier in this lesson on your purpose and audience. Reviewing these will put both you and Mariah in the proper mind-set to start.

The following is Mariah’s thesis statement.

Here are the notes that Mariah wrote to herself to characterize her purpose and audience.

Mariah chose to begin by writing a quick introduction based on her thesis statement. She knew that she would want to improve her introduction significantly when she revised. Right now, she just wanted to give herself a starting point.

With her thesis statement and her purpose and audience notes in front of her, Mariah then looked at her sentence outline. She chose to use that outline because it includes the topic sentences. The following is the portion of her outline for the first body paragraph. The Roman numeral II identifies the topic sentence for the paragraph, capital letters indicate supporting details, and Arabic numerals label subpoints.

Mariah then began to expand the ideas in her outline into a paragraph. Notice how the outline helped her guarantee that all her sentences in the body of the paragraph develop the topic sentence.

When you make major changes to a draft, save the different version as a different document with a different title—such as draft 1, draft 2, and so on—so that you will have a complete history of drafts. This can come in handy when later changing your mind about a direction you went with a draft.

Study how Mariah made the transition from her sentence outline to her first draft. First, copy her outline onto your own sheet of paper. Leave a few spaces between each part of the outline. Then copy sentences from Mariah’s paragraph to align each sentence with its corresponding entry in her outline.

Examples of Continuing a Draft

Mariah continued writing her essay, moving to the second and third body paragraphs. She had supporting details but no numbered subpoints in her outline, so she had to consult her prewriting notes for specific information to include.

If you decide to take a break between finishing your first body paragraph and starting the next one, do not start writing immediately when you return to your work. Put yourself back in context and in the mood by rereading what you have already written. This is what Mariah did. If she had stopped writing in the middle of writing the paragraph, she could have jotted down some quick notes to herself about what she would write next.

Preceding each body paragraph that Mariah wrote is the appropriate section of her sentence outline. Notice how she expanded Roman numeral III from her outline into a first draft of the second body paragraph. As you read, ask yourself how closely she stayed on purpose and how well she paid attention to the needs of her audience.

Mariah then began her third and final body paragraph using Roman numeral IV from her outline.

Re-read body paragraphs two and three of the essay that Mariah is writing.

- In body paragraph two, Mariah decided to develop her paragraph as a nonfiction narrative. Do you agree with her decision? Explain. How else could she have chosen to develop the paragraph? Why is that better?

- Compare the writing styles of paragraphs two and three. What evidence do you have that Mariah was getting tired or running out of steam? What advice would you give her? Why?

- Choose one of these two body paragraphs. Write a version of your own that you think better fits Mariah’s audience and purpose.

The Writing Textbook Copyright © 2021 by Josh Woods, editor and contributor, as well as an unnamed author (by request from the original publisher), and other authors named separately is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Writing a Paper: Drafting

Drafting refers to actually writing the words of the paper. As part of the writing process, you will write multiple drafts of your paper. Each rough draft improves upon the previous one. The final draft is simply the last draft that you submit.

Related Webinar

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Organizing Your Thoughts

- Next Page: Introductions

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Certification, Licensure and Compliance

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

writingxhumanities

A "how to" guide for UC Berkeley writers

Drafting | Revising | Editing

Keep in mind that your first draft is preliminary , meaning that you should feel free to experiment with many different ways of generating ideas , from brainstorming to mind-mapping to more traditional outlining to literally just beginning to write. If you think that you’re going to use a certain piece of evidence you found in your preliminary close reading of the text, you can start by simply writing a paragraph in which you use that evidence to make a tentative claim. This is a great way to conquer the fear of the blank page, and another benefit of using close reading to develop your argument!

In other words, you shouldn’t assume that you can’t start writing until you know exactly what you’re going to argue or what sequence in which you’ll present your claims and evidence. Likewise, you shouldn’t believe that just because you’ve written something, you can’t change it later, perhaps dramatically. Much like close reading and making an argument, drafting is an iterative and recursive process, which means that it proceeds in a looping way through multiple phases of repetition—your first draft is just a beginning, an early form of your essay that is open to change and subject to revision. You can narrow or refine your focus as you move through multiple drafts, and your essay is likely to evolve, both in argument and structure, as your drafting progresses. And that’s a good thing!

Some writers like to make a provisional outline before they begin drafting, while others begin to write with only a rough plan in mind. Whether you prefer to outline first or not here are some strategies for keeping your argument in focus before, during, and after drafting.

Sometimes “revision” and “editing” are used interchangeably, but each has a distinct role in the writing process–and each can help you to develop and refine your work in important ways. Revision is the process of contemplating and making changes to the conceptual or argument-driven work of an essay. In revision, you might refine your argument, examine the close readings and other forms of analysis that move your argument forward, or reconsider the structure that knits your ideas together.

Editing, on the other hand, means contemplating and making changes to the language with which we express our ideas. Editing helps us to “speak” more clearly: to correct our mechanical errors (grammar, typos, etc.), clarify our language, more smoothly integrate quotations or other citations, and so forth. Editing doesn’t ask, what am I trying to say? Instead, it asks: am I saying it well?

While both revising and editing are important parts of the writing process, it tends to be counterproductive to do both at the same time. Why spend time polishing sentences or paragraphs that you may end up cutting? And once you’ve spent time polishing your prose, it’s much harder to cut or rework that part of your essay!

When you first return to a draft for the purpose of revision, you should focus on larger questions of substance and structure. What is your argument? What evidence do you provide? Is your analysis convincing? Is your essay clearly organized? Revision often requires you to make “big” changes: you may need to re-focus your argument or refine your ideas; cut, move, or rewrite whole paragraphs; add additional sources or evidence; rework your introduction and/or conclusion to bring them in line with the argument you have made. Remember that rewriting is the key to good writing.

Here are some strategies you can use to revise an essay:

- As you tackle the revision process, consider your priorities for revision . What is the most important thing to work on? What next?

- Remember to approach revision as a multi-step process. You can make this process manageable by focusing on two or three areas during each revision session . Conclude the revision process by checking balance, assessing your organization, and asking if you’ve kept your promises to your readers.

- Generate a reverse outline , which is one of the most useful tools in the essay reviser’s toolbox. Whether you make your reverse outline in the margins of your draft or on a separate sheet of paper , this strategy will help you to see the overall structure of your argument as it stands in your draft, the first step in determining whether (and how) reorganizing the sequence of paragraphs might strengthen your argument. It can also help you determine whether all paragraphs are working to support your main claim; whether there are any redundant paragraphs (i.e., paragraphs that make the same point as other paragraphs without moving your argument forward); or whether there is any missing or unclear evidence.

- Consider whether your essay uses transitional words and phrases between paragraphs to clarify the arc of your argument.

- Consider whether your paragraphs themselves are clearly structured , with topic sentences and transitional sentences that signpost the development of your argument and don’t rely solely on the chronology of a text. (This will help you to avoid doing a plot summary or merely describing a text rather than doing an analysis!)

- All of these steps may help you to take the most important step of all: determining whether you have a sufficiently focused and compelling thesis that you have supported persuasively with textual evidence. (For more on developing a strong thesis, see What Are Some Critical Moves in an Argument? .)

- If you’ve already received feedback on your paper from your instructor, think about how you might incorporate their suggestions in your next draft or your next essay. Don’t be shy about arranging to meet with them to discuss their feedback and how you can best use it in revision and future essays.

Once you have reworked the structure of your argument in the revising phase, you’ll be ready to start editing. Editing means honing the language of your essay in order to make your argument clear, engaging, and persuasive to your reader. It can include editing to improve the style of your writing as well as to fix mechanical errors (a kind of editing often called proofreading). Mechanical details such as correct punctuation and grammar are fundamental to conveying your meaning to your reader. While unintentional errors like typos might seem trivial to you, prose that is typo-free will immediately help you gain your reader’s confidence.

Re-reading your paper carefully can help you find a variety of errors that a computer spell-checker might miss. In order to focus on the language of your own writing, try some of these editing strategies:

- Reading your paper aloud—or, even better, having a friend or your computer’s text-to-speech function read your paper aloud to you—is a great way to catch things your eye might miss on the page. As you hear your paper, listen for sentences that sound awkward. Trust your ear!

- Reading your sentences individually and out of context—editing each of the first sentences in each of your paragraphs, then the second sentences, etc.—is another way to focus on the form of your sentences rather than their content.

- Sometimes printing out your paper, especially if you’ve only looked at an electronic copy up to this point, can also help.

- Perhaps the best way to notice things you’ve missed is by setting your writing aside and coming back to it later. Take a break—you earned it!

Here’s a list of some additional editing strategies ; you might also consider the Paramedic Method , a streamlined approach to achieving persuasive and clear prose. And here are some resources to help with common grammatical errors:

- One-Stop Guide to Common Errors

- Basic Punctuation Rules

- Semi-colons, Colons, and Dashes

- Run-on Sentences

- Dangling Modifiers

Even if your writing is grammatically correct, you still need to edit it for style. Style—the way you put together a sentence or a group of sentences—is subjective; different people have different ideas about what sounds good. But the following guidelines can help you write lucidly, engagingly and, yes, stylishly.

- Use a voice or tone appropriate to the academic discipline in which you are working. New writers are often surprised, for example, that humanities essay writers sometimes use first person pronouns . When in doubt, ask your instructor for guidance and even for examples of the style of writing you are expected to do for their class.

- Avoid jargon and other kinds of over-inflated language. Use theoretical terms if they are critical to your argument, but make sure to define them for the reader. And always make sure that the word you’re using means what you think it means! Having a sure command of the language you are using not only assures the clarity of your writing, but it also helps to make your writing expressive and polished, contributing to the authority of your voice as a writer.

- Watch out for wordiness . When you streamline your prose, your reader will understand your idea more easily. Vary your diction to avoid sounding robotic, but don’t go overboard—sometimes you need to repeat words or phrases to help your reader follow the main thread of your argument. Likewise, vary sentence structure ( including sentence length) to create a feeling of flow, but never at the expense of clarity.

- In order to grasp what’s happening in a sentence, a reader needs to understand who or what is doing something and what it is they are doing. One way to make the subject and the verb of your sentence clear to your reader is by making sure the passive voice is avoided; for an example of unclear and “baggy” use of the passive voice, see the first half of this sentence! (Here’s one fix: “By avoiding the passive voice, you can help your reader to recognize your sentence’s subject and verb.” Here’s another: “To help your reader, avoid the passive voice!”) You should also avoid clunky nominalizations, also known as “ zombie nouns ,” which means using the noun form of a verb (such as “nominalization” instead of “nominalize”) or the noun form of an adjective (“implacability” instead of “implacable”). Of course, you may have a good reasons to use these grammatical forms in specific contexts; you might use the passive voice to describe the writing of an anonymous poem, for example, or employ a nominalization if it is a commonly used technical term such as “enjambment.” But otherwise, search for and replace passive verb constructions and nominalizations to make your sentences concrete, clear and lively.

For more general hints on improving your prose style, you can check out this overview or—as always—talk to your instructor!.

For additional materials, go to Teaching Drafting | Revising | Editing in the For Instructors section of this website.

Get 50% OFF Yearly And Lifetime Plans This Cyber Monday

From Draft to Done: A Full Breakdown of the Writing Process

By Micah McGuire

So you’ve decided to write a story and hope to publish it. For write-to-publish newbies, you might want to know what you’re getting into, especially if you’re working on a large project like a novel. It’s natural to wonder: how many drafts will it take before my story is ready to publish?

Unfortunately, you’re more likely to answer “how many licks does it take to get to the center of a Tootsie pop?” before knowing how many drafts you’ll need before publication. Here’s why.

A rose by any other name: What’s in a draft?

The biggest problem with breaking down the writing process from first to last draft can be linked back to one little detail:

How do you define a draft?

There are as many ways to define the word “draft” as there are writers. Which means every writer’s version of “the writing process” will look different. It’s impossible to say: “oh, writing a novel will take five drafts.”

Because the definition of “draft” can vary so much, it’s useful to think about drafting on a spectrum:

- The fewest drafts: Only rewrites count

- Middle-of-the-road: The fiction patching method

- The most drafts: Every change counts

Keep reading for more on how this draft spectrum works.

Only rewrites count

The minimalist take on drafting. By this definition, only full rewrites of a piece count as a true draft. Which means when saving a manuscript to a file, you wouldn’t alter the file name until you completely rewrite that chapter, section, or piece.

The advantage here lies in simplicity: you have fewer files to juggle since you’re saving to the same file over and over. But you may risk losing details from earlier drafts because of the repeat saves. Plus, for larger projects like novels, you need to divide your manuscript into parts and have a file system in place to keep track of your revisions.

The fiction patching method

While this started as more of a joke between writers on social media, it’s a great middle-of-the-road way to think about drafting. It takes cues from software versioning , noting that not every change means a new draft. Smaller changes are like patches (the version’s third number) and rewrites might be closer to updates (the second number) rather than a new version release/new draft (the first number).

So draft names might look like this:

- Draft 0.1: Outline

- Draft 1.0: Rough Draft

- Draft 1.5: Rough draft with some rewrites

- Draft 2.0: Rough draft fully rewritten with feedback from critique partners

- Draft 2.0.1: Rewritten rough draft with a minor tweak (or “patch”) to the protagonist’s motivation

Here, you can always revisit an older version to review details you want to re-emphasize in rewrites. But, it’s easy to end up with dozens if not hundreds of files and you’ll have to decide what constitutes a “patch,” an update and a brand new release ahead of time to stay consistent with naming.

Every change counts

Taken to its extreme, this approach to drafting may seem silly. Why would anyone count every change as a new draft? But most writers favor a less extreme version of this approach. It’s how we end up with draft names like “Final draft” and “Final draft I swear,” and “No really this is the last draft.”

Fortunately, this means you’ll never lose a detail again and you have complete control over naming conventions. However, you can end up with hundreds of files in a blink. And, if you’re not careful with what you name each file, it may take some detective work to figure out which one is the most recent version.

So, where do you fall on the drafting spectrum? Keeping it in mind can help you estimate the number of drafts you might need before publishing your story.

From outline to finished product: the writing process

Now that you have a better understanding of what the word “draft” means to you, you can look at the writing process with fresh eyes.

While it’s impossible to say how many drafts a manuscript takes, it is possible to break the writing process down into stages . We can define the process in 5 stages:

- The rough draft

- Content edits

- Proofreading

Try not to think of this as a step-by-step process. It’s more like a series of loops as each one of these stages may require multiple revision rounds. Sometimes, the process can feel like one step forward and two steps back, but each round will strengthen your manuscript.

Let’s look at each stage.

1. Outlining

2. the rough draft, 3. content edits, 4. line edits, 5. proofreading.

We couldn’t talk about the writing process without touching on outlining. Planners, applaud and cheer as much as you’d like—just make sure not to upset your color-coded highlighter sets.

Pantsers, resist the urge to skip this. It still applies to you, even if you think it doesn’t.

Like a draft, there are thousands of ways to define the term “outline.” But whether you fall on the planner detailed scene-by-scene index card method or the pantser “I know the ending. How I get there is up to the characters” end of the spectrum, you need some form of an outline.

The point of an outline is to ensure your writing produces a story with a plot. Otherwise, you risk writing pages and pages in which your characters run around and do things but never advance the plot.

So at the bare minimum, an outline requires you know:

- Who your protagonist is

- Who your antagonist is

- Why the protagonist and antagonist have a problem with each other (otherwise known as your central conflict)

- Where the story starts

- Where the story ends

Pantsers, breathe a sigh of relief: you don’t have to answer any of these questions in detail for it to count as an outline. You just need to know where you’re starting and where you’re going. You don’t even need to use a pen and paper— try these three fun outlining methods .

Spend as much or as little time on this stage as you’d like.

But once your outline is complete, you can move onto what most of us think of as the “real” writing: drafting.