- Email Signup

Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology

World Religions Overview Essay

The Movement of Religion and Ecology: Emerging Field and Dynamic Force

Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim, Yale University

Originally published in the Routledge Handbook of Religion and Ecology

As many United Nations reports attest, we humans are destroying the life-support systems of the Earth at an alarming rate. Ecosystems are being degraded by rapid industrialization and relentless development. The data keeps pouring in that we are altering the climate and toxifying the air, water, and soil of the planet so that the health of humans and other species is at risk. Indeed, the Swedish scientist, Johan Rockstrom, and his colleagues, are examining which planetary boundaries are being exceeded. (Rockstrom and Klum, 2015)

The explosion of population from 3 billion in 1960 to more then 7 billion currently and the subsequent demands on the natural world seem to be on an unsustainable course. The demands include meeting basic human needs of a majority of the world’s people, but also feeding the insatiable desire for goods and comfort spread by the allure of materialism. The first is often called sustainable development; the second is unsustainable consumption. The challenge of rapid economic growth and consumption has brought on destabilizing climate change. This is coming into full focus in alarming ways including increased floods and hurricanes, droughts and famine, rising seas and warming oceans.

Can we turn our course to avert disaster? There are several indications that this may still be possible. On September 25, 2015 after the Pope addressed the UN General Assembly, 195 member states adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). On December 12, 2015 these same members states endorsed the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. Both of these are important indications of potential reversal. The Climate Agreement emerged from the dedicated work of governments and civil society along with business partners. The leadership of UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon and the Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, Christiana Figueres, and many others was indispensable.

One of the inspirations for the Climate Agreement and for the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals was the release of the Papal Encyclical, Laudato Si’ in June 2015. The encyclical encouraged the moral forces of concern for both the environment and people to be joined in “integral ecology”. “The cry of the Earth and the cry of the poor” are now linked as was not fully visible before. (Boff, 1997 and in the encyclical) Many religious and environmental communities are embracing this integrated perspective and will, no doubt, foster it going forward. The question is how can the world religions contribute more effectively to this renewed ethical momentum for change. For example, what will be their long-term response to population growth? As this is addressed in the article by Robert Wyman and Guigui Yao, we will not take it up here. Instead, we will consider some of the challenges and possibilities amid the dream of progress and the lure of consumption.

Challenges: The Dream of Progress and the Religion of Consumption

Consumption appears to have become an ideology or quasi-religion, not only in the West but also around the world. Faith in economic growth drives both producers and consumers. The dream of progress is becoming a distorted one. This convergence of our unlimited demands with an unquestioned faith in economic progress raises questions about the roles of religions in encouraging, discouraging, or ignoring our dominant drive toward appropriately satisfying material needs or inappropriately indulging material desires. Integral ecology supports the former and critiques the latter.

Moreover, a consumerist ideology depends upon and simultaneously contributes to a worldview based on the instrumental rationality of the human. That is, the assumption for decision-making is that all choices are equally clear and measurable. Market based metrics such as price, utility, or efficiency are dominant. This can result in utilitarian views of a forest as so much board feet or simply as a mechanistic complex of ecosystems that provide services to the human.

One long-term effect of this is that the individual human decision-maker is further distanced from nature because nature is reduced to measurable entities for profit or use. From this perspective we humans may be isolated in our perceived uniqueness as something apart from the biological web of life. In this context, humans do not seek identity and meaning in the numinous beauty of the world, nor do they experience themselves as dependent on a complex of life-supporting interactions of air, water, and soil. Rather, this logic sees humans as independent, rational decision-makers who find their meaning and identity in systems of management that now attempt to co-opt the language of conservation and environmental concern. Happiness is derived from simply creating and having more material goods. This perspective reflects a reading of our current geological period as human induced by our growth as a species that is now controlling the planet. This current era is being called the “Anthropocene” because of our effect on the planet in contrast to the prior 12,000 year epoch known as the Holocene.

This human capacity to imagine and implement a utilitarian-based worldview regarding nature has undermined many of the ancient insights of the world’s religious and spiritual traditions. For example, some religions, attracted by the individualistic orientations of market rationalism and short-term benefits of social improvement, seized upon material accumulation as containing divine sanction. Thus, Max Weber identified the rise of Protestantism with an ethos of inspirited work and accumulated capital.

Weber also identified the growing disenchantment from the world of nature with the rise of global capitalism. Karl Marx recognized the “metabolic rift” in which human labor and nature become alienated from cycles of renewal. The earlier mystique of creation was lost. Wonder, beauty, and imagination as ways of knowing were gradually superseded by the analytical reductionism of modernity such that technological and economic entrancement have become key inspirations of progress.

Challenges: Religions Fostering Anthropocentrism

This modern, instrumental view of matter as primarily for human use arises in part from a dualistic Western philosophical view of mind and matter. Adapted into Jewish, Christian and Islamic religious perspectives, this dualism associates mind with the soul as a transcendent spiritual entity given sovereignty and dominion over matter. Mind is often valued primarily for its rationality in contrast to a lifeless world. At the same time we ensure our radical discontinuity from it.

Interestingly, views of the uniqueness of the human bring many traditional religious perspectives into sync with modern instrumental rationalism. In Western religious traditions, for example, the human is seen as an exclusively gifted creature with a transcendent soul that manifests the divine image and likeness. Consequently, this soul should be liberated from the material world. In many contemporary reductionist perspectives (philosophical and scientific) the human with rational mind and technical prowess stands as the pinnacle of evolution. Ironically, religions emphasizing the uniqueness of the human as the image of God meet market-driven applied science and technology precisely at this point of the special nature of the human to justify exploitation of the natural world. Anthropocentrism in various forms, religious, philosophical, scientific, and economic, has led, perhaps inadvertently, to the dominance of humans in this modern period, now called the Anthropocene. (It can be said that certain strands of the South Asian religions have emphasized the importance of humans escaping from nature into transcendent liberation. However, such forms of radical dualism are not central to the East Asian traditions or indigenous traditions.)

From the standpoint of rational analysis, many values embedded in religions, such as a sense of the sacred, the intrinsic value of place, the spiritual dimension of the human, moral concern for nature, and care for future generations, are incommensurate with an objectified monetized worldview as they not quantifiable. Thus, they are often ignored as externalities, or overridden by more pragmatic profit-driven considerations. Contemporary nation-states in league with transnational corporations have seized upon this individualistic, property-based, use-analysis to promote national sovereignty, security, and development exclusively for humans.

Possibilities: Systems Science

Yet, even within the realm of so-called scientific, rational thought, there is not a uniform approach. Resistance to the easy marriage of reductionist science and instrumental rationality comes from what is called systems science and new ecoogy. By this we refer to a movement within empirical, experimental science of exploring the interaction of nature and society as complex dynamic systems. This approach stresses both analysis and synthesis – the empirical act of observation, as well as placement of the focus of study within the context of a larger whole. Systems science resists the temptation to take the micro, empirical, reductive act as the complete description of a thing, but opens analysis to the large interactive web of life to which we belong, from ecosystems to the biosphere. There are numerous examples of this holistic perspective in various branches of ecology. And this includes overcoming the nature-human divide. (Schmitz 2016) Aldo Leopold understood this holistic interconnection well when he wrote: “We abuse land because we see it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” (Leopold, 1966)

Collaboration of Science and Religion

Within this inclusive framework, scientists have been moving for some time beyond simply distanced observations to engaged concern. The Pope’s encyclical, Laudato Si , has elevated the level of visibility and efficacy of this conversation between science and religion as perhaps never before on a global level. Similarly, many other statements from the world religions are linking the wellbeing of people and the planet for a flourishing future. For example, the World Council of Churches has been working for four decades to join humans and nature in their program on Justice, Peace, and the Integrity of Creation.

Many scientists such as Thomas Lovejoy, E.O. Wilson, Jane Lubchenco, Peter Raven, and Ursula Goodenough recognize the importance of religious and cultural values when discussing solutions to environmental challenges. Other scientists such as Paul Ehrlich and Donald Kennedy have called for major studies of human behavior and values in relation to environmental issues. ( Science , July 2005) This has morphed into the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. (mahb.standford.edu). Since 2009 the Ecological Society of America has established an Earth Stewardship Initiative with yearly panels and publications. Many environmental studies programs are now seeking to incorporate these broader ethical and behavioral approaches into the curriculum.

Possibilities: Extinction and Religious Response

The stakes are high, however, and the path toward limiting ourselves within planetary boundaries is not smooth. Scientists are now reporting that because of the population explosion, our consuming habits, and our market drive for resources, we are living in the midst of a mass extinction period. This period represents the largest loss of species since the extinction of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago when the Cenozoic period began. In other words, we are shutting down life systems on the planet and causing the end of this large-scale geological era with little awareness of what we are doing or its consequences.

As the cultural historian Thomas Berry observed some years ago, we are making macrophase changes on the planet with microphase wisdom. Indeed, some people worry that these rapid changes have outstripped the capacity of our religions, ethics, and spiritualities to meet the complex challenges we are facing.

The question arises whether the wisdom traditions of the human community, embedded in institutional religions and beyond, can embrace integral ecology at the level needed? Can the religions provide leadership into a synergistic era of human-Earth relations characterized by empathy, regeneration, and resilience? Or are religions themselves the wellspring of those exclusivist perspectives in which human societies disconnect themselves from other groups and from the natural world? Are religions caught in their own meditative promises of transcendent peace and redemptive bliss in paradisal abandon? Or does their drive for exclusive salvation or truth claims cause them to try to overcome or convert the Other?

Authors in this volume are exploring these issues within religious and spiritual communities regarding the appropriate responses of the human to our multiple environmental and social challenges. What forms of symbolic visioning and ethical imagining can call forth a transformation of consciousness and conscience for our Earth community? Can religions and spiritualites provide vision and inspiration for grounding and guiding mutually enhancing human-Earth relations? Have we arrived at a point where we realize that more scientific statistics on environmental problems, more legislation, policy or regulation, and more economic analysis, while necessary, are no longer sufficient for the large-scale social transformations needed? This is where the world religions, despite their limitations, surely have something to contribute.

Such a perspective includes ethics, practices, and spiritualities from the world’s cultures that may or may not be connected with institutional forms of religion. Thus spiritual ecology and nature religions are an important part of the discussions and are represented in this volume. Our own efforts have focused on the world religions and indigenous traditions. Our decade long training in graduate school and our years of living and traveling throughout Asia and the West gave us an early appreciation for religions as dynamic, diverse, living traditions. We are keenly aware of the multiple forms of syncretism and hybridization in the world religions and spiritualties. We have witnessed how they are far from monolithic or impervious to change in our travels to more than 60 countries.

Problems and Promise of Religions

Several qualifications regarding the various roles of religion should thus be noted. First, we do not wish to suggest here that any one religious tradition has a privileged ecological perspective. Rather, multiple interreligious perspectives may be the most helpful in identifying the contributions of the world religions to the flourishing of life.

We also acknowledge that there is frequently a disjunction between principles and practices: ecologically sensitive ideas in religions are not always evident in environmental practices in particular civilizations. Many civilizations have overused their environments, with or without religious sanction.

Finally, we are keenly aware that religions have all too frequently contributed to tensions and conflict among various groups, both historically and at present. Dogmatic rigidity, inflexible claims of truth, and misuse of institutional and communal power by religions have led to tragic consequences in many parts of the globe.

Nonetheless, while religions have often preserved traditional ways, they have also provoked social change. They can be limiting but also liberating in their outlooks. In the twentieth century, for example, religious leaders and theologians helped to give birth to progressive movements such as civil rights for minorities, social justice for the poor, and liberation for women. Although the world religions have been slow to respond to our current environmental crises, their moral authority and their institutional power may help effect a change in attitudes, practices, and public policies. Now the challenge is a broadening of their ethical perspectives.

Traditionally the religions developed ethics for homicide, suicide, and genocide. Currently they need to respond to biocide, ecocide, and geocide. (Berry, 2009)

Retrieval, Reevaluation, Reconstruction

There is an inevitable disjunction between the examination of historical religious traditions in all of their diversity and complexity and the application of teachings, ethics, or practices to contemporary situations. While religions have always been involved in meeting contemporary challenges over the centuries, it is clear that the global environmental crisis is larger and more complex than anything in recorded human history. Thus, a simple application of traditional ideas to contemporary problems is unlikely to be either possible or adequate. In order to address ecological problems properly, religious and spiritual leaders, laypersons and academics have to be in dialogue with scientists, environmentalists, economists, businesspeople, politicians, and educators. Hence the articles in this volume are from various key sectors.

With these qualifications in mind we can then identify three methodological approaches that appear in the still emerging study of religion and ecology. These are retrieval, reevaluation, and reconstruction. Retrieval involves the scholarly investigation of scriptural and commentarial sources in order to clarify religious perspectives regarding human-Earth relations. This requires that historical and textual studies uncover resources latent within the tradition. In addition, retrieval can identify ethical codes and ritual customs of the tradition in order to discover how these teachings were put into practice. Traditional environmental knowledge (TEK) is an important part of this for all the world religions, especially indigenous traditions.

With reevaluation, traditional teachings are evaluated with regard to their relevance to contemporary circumstances. Are the ideas, teachings, or ethics present in these traditions appropriate for shaping more ecologically sensitive attitudes and sustainable practices? Reevaluation also questions ideas that may lead to inappropriate environmental practices. For example, are certain religious tendencies reflective of otherworldly or world-denying orientations that are not helpful in relation to pressing ecological issues? It asks as well whether the material world of nature has been devalued by a particular religion and whether a model of ethics focusing solely on human interactions is adequate to address environmental problems.

Finally, reconstruction suggests ways that religious traditions might adapt their teachings to current circumstances in new and creative ways. These may result in new syntheses or in creative modifications of traditional ideas and practices to suit modern modes of expression. This is the most challenging aspect of the emerging field of religion and ecology and requires sensitivity to who is speaking about a tradition in the process of reevaluation and reconstruction. Postcolonial critics have appropriately highlighted the complex issues surrounding the problem of who is representing or interpreting a religious tradition or even what constitutes that tradition. Nonetheless, practitioners and leaders of particular religions are finding grounds for creative dialogue with scholars of religions in these various phases of interpretation.

Religious Ecologies and Religious Cosmologies

As part of the retrieval, reevaluation, and reconstruction of religions we would identify “religious ecologies” and “religious cosmologies” as ways that religions have functioned in the past and can still function at present. Religious ecologies are ways of orienting and grounding whereby humans undertake specific practices of nurturing and transforming self and community in a particular cosmological context that regards nature as inherently valuable. Through cosmological stories humans narrate and experience the larger matrix of mystery in which life arises, unfolds, and flourishes. These are what we call religious cosmologies. These two, namely religious ecologies and religious cosmologies, can be distinguished but not separated. Together they provide a context for navigating life’s challenges and affirming the rich spiritual value of human-Earth relations.

Human communities until the modern period sensed themselves as grounded in and dependent on the natural world. Thus, even when the forces of nature were overwhelming, the regenerative capacity of the natural world opened a way forward. Humans experienced the processes of the natural world as interrelated, both practically and symbolically. These understandings were expressed in traditional environmental knowledge, namely, in hunting and agricultural practices such as the appropriate use of plants, animals, and land. Such knowledge was integrated in symbolic language and practical norms, such as prohibitions, taboos, and limitations on ecosystems’ usage. All this was based in an understanding of nature as the source of nurturance and kinship. The Lakota people still speak of “all my relations” as an expression of this kinship. Such perspectives will need to be incorporated into strategies to solve environmental problems. Humans are part of nature and their cultural and religious values are critical dimensions of the discussion.

Multidisciplinary approaches: Environmental Humanities

We are recognizing, then, that the environmental crisis is multifaceted and requires multidisciplinary approaches. As this book indicates, the insights of scientific modes of analytical and synthetic knowing are indispensable for understanding and responding to our contemporary environmental crisis. So also, we need new technologies such as industrial ecology, green chemistry, and renewable energy. Clearly ecological economics is critical along with green governance and legal policies as articles in this volume illustrate.

In this context it is important to recognize different ways of knowing that are manifest in the humanities, such as artistic expressions, historical perspectives, philosophical inquiry, and religious understandings. These honor emotional intelligence, affective insight, ethical valuing, and spiritual awakening.

Environmental humanities is a growing and diverse area of study within humanistic disciplines. In the last several decades, new academic courses and programs, research journals and monographs, have blossomed. This broad-based inquiry has sparked creative investigation into multiple ways, historically and at present, of understanding and interacting with nature, constructing cultures, developing communities, raising food, and exchanging goods.

It is helpful to see the field of religion and ecology as part of this larger emergence of environmental humanities. While it can be said that environmental history, literature, and philosophy are some four decades old, the field of religions and ecology began some two decades ago. It was preceded, however, by work among various scholars, particularly Christian theologians. Some eco-feminists theologians, such as Rosemary Ruether and Sallie McFague, Mary Daly, and Ivone Gebara led the way.

The Emerging Field of Religion and Ecology

An effort to identify and to map religiously diverse attitudes and practices toward nature was the focus of a three-year international conference series on world religions and ecology . Organized by Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim, ten conferences were held at the Harvard Center for the Study of World Religions from 1996-1998 that resulted in a ten volume book series (1997-2004). Over 800 scholars of religion and environmentalists participated. The director of the Center, Larry Sullivan, gave space and staff for the conferences. He chose to limit their scope to the world religions and indigenous religions rather than “nature religions”, such as wicca or paganism, which the organizers had hoped to include.

Culminating conferences were held in fall 1998 at Harvard and in New York at the United Nations and the American Museum of Natural History where 1000 people attended and Bill Moyers presided. At the UN conference Tucker and Grim founded the Forum on Religion and Ecology, which is now located at Yale. They organized a dozen more conferences and created an electronic newsletter that is now sent to over 12,000 people around the world. In addition, they developed a major website for research, education, and outreach in this area (fore.yale.edu). The conferences, books, website, and newsletter have assisted in the emergence of a new field of study in religion and ecology. Many people have helped in this process including Whitney Bauman and Sam Mickey who are now moving the field toward discussing the need for planetary ethics. A Canadian Forum on Religion and Ecology was established in 2002, a European Forum for the Study of Religion and the Environment was formed in 2005, and a Forum on Religion and Ecology @ Monash in Australia in 2011.

Courses on this topic are now offered in numerous colleges and universities across North America and in other parts of the world. A Green Seminary Initiative has arisen to help educate seminarians. Within the American Academy of Religion there is a vibrant group focused on scholarship and teaching in this area. A peer-reviewed journal, Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture, and Ecology , is celebrating its 25 th year of publication. Another journal has been publishing since 2007, the Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature, and Culture . A two volume Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature edited by Bron Taylor has helped shape the discussions, as has the International Society for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture he founded. Clearly this broad field of study will continue to expand as the environmental crisis grows in complexity and requires increasingly creative interdisciplinary responses.

The work in religion and ecology rests in an intersection between the academic field within education and the dynamic force within society. This is why we see our work not so much as activist, but rather as “engaged scholarship” for the flourishing of our shared planetary life. This is part of a broader integration taking place to link concerns for both people and the planet. This has been fostered in part by the twenty-volume Ecology and Justice Series from Orbis Books and with the work of John Cobb, Larry Rasmussen, Dieter Hessel, Heather Eaton, Cynthia Moe-Loebeda, and others. The Papal Encyclical is now highlighting this linkage of eco-justice as indispensable for an integral ecology.

The Dynamic Force of Religious Environmentalism

All of these religious traditions, then, are groping to find the languages, symbols, rituals, and ethics for sustaining both ecosystems and humans. Clearly there are obstacles to religions moving into their ecological, eco-justice, and planetary phases. The religions are themselves challenged by their own bilingual languages, namely, their languages of transcendence, enlightenment, and salvation; and their languages of immanence, sacredness of Earth, and respect for nature. Yet, as the field of religion and ecology has developed within academia, so has the force of religious environmentalism emerged around the planet. Roger Gottlieb documents this in his book A Greener Faith . (Gottlieb 2006) The Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew held international symposia on “Religion, Science and the Environment” focused on water issues (1995-2009) that we attended. He has made influential statements on this issue for 20 years. The Parliament of World Religions has included panels on this topic since 1998 and most expansively in 2015. Since 1995 the UK based Alliance of Religion and Conservation (ARC), led by Martin Palmer, has been doing significant work with religious communities around under the patronage of Prince Philip.

These efforts are recovering a sense of place, which is especially clear in the environmental resilience and regeneration practices of indigenous peoples. It is also evident in valuing the sacred pilgrimage places in the Abrahamic traditions (Jerusalem, Rome, and Mecca) both historically and now ecologically. So also East Asia and South Asia attention to sacred mountains, caves, and other pilgrimage sites stands in marked contrast to massive pollution.

In many settings around the world religious practitioners are drawing together religious ways of respecting place, land, and life with understanding of environmental science and the needs of local communities. There have been official letters by Catholic Bishops in the Philippines and in Alberta, Canada alarmed by the oppressive social conditions and ecological disasters caused by extractive industries. Catholic nuns and laity in North America, Australia, England, and Ireland sponsor educational programs and conservation plans drawing on the eco-spiritual vision of Thomas Berry and Brian Swimme. Also inspired by Berry and Swimme, Paul Winter’s Solstice celebrations and Earth Mass at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York Winter have been taking place for three decades.

Even in the industrial growth that grips China, there are calls from many in politics, academia, and NGOs to draw on Confucian, Daoist, and Buddhist perspectives for environmental change. In 2008 we met with Pan Yue, the Deputy Minister of the Environment, who has studied these traditions and sees them as critical to Chinese environmental ethics. In India, Hinduism is faced with the challenge of clean up of sacred rivers, such as the Ganges and the Yamuna. To this end in 2010 with Hindu scholars, David Haberman and Christopher Chapple, we organized a conference of scientists and religious leaders in Delhi and Vrindavan to address the pollution of the Yamuna.

Many religious groups are focused on climate change and energy issues. For example, InterFaith Power and Light and GreenFaith are encouraging religious communities to reduce their carbon footprint. Earth Ministry in Seattle is leading protests against oil pipelines and terminals. The Evangelical Environmental Network and other denominations are emphasizing climate change as a moral issue that is disproportionately affecting the poor. In Canada and the US the Indigenous Environmental Network is speaking out regarding damage caused by resource extraction, pipelines, and dumping on First Peoples’ Reserves and beyond. All of the religions now have statements on climate change as a moral issue and they were strongly represented in the People’s Climate March in September 2015. Daedalus, the journal of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, published the first collection of articles on religion and climate change from two conferences we organized there. (Tucker & Grim, 2001)

Striking examples of religion and ecology have occurred in the Islamic world. In June 2001 and May 2005 the Islamic Republic of Iran led by President Khatami and the United Nations Environment Programme sponsored conferences in Tehran that we attended. They were focused on Islamic principles and practices for environmental protection. The Iranian Constitution identifies Islamic values for ecology and threatens legal sanctions. One of the earliest spokespersons for religion and ecology is the Iranian scholar, Seyyed Hossein Nasr. Fazlun Khalid in the UK founded the Islamic Foundation for Ecology and Environmental Science. In Indonesia in 2014 a fatwa was issued declaring that killing an endangered species is prohibited.

These examples illustrate ways in which an emerging alliance of religion and ecology is occurring around the planet. These traditional values within the religions now cause them to awaken to environmental crises in ways that are strikingly different from science or policy. But they may find interdisciplinary ground for dialogue in concerns for eco-justice, sustainability, and cultural motivations for transformation. The difficulty, of course, is that the religions are often preoccupied with narrow sectarian interests. However, many people, including the Pope, are calling on the religions to go beyond these interests and become a moral leaven for change.

Renewal Through Laudato Si’

Pope Francis is highlighting an integral ecology that brings together concern for humans and the Earth. He makes it clear that the environment can no longer be seen as only an issue for scientific experts, or environmental groups, or government agencies alone. Rather, he invites all people, programs and institutions to realize these are complicated environmental and social problems that require integrated solutions beyond a “technocratic paradigm” that values an easy fix. Within this integrated framework, he urges bold new solutions.

In this context Francis suggests that ecology, economics, and equity are intertwined. Healthy ecosystems depend on a just economy that results in equity. Endangering ecosystems with an exploitative economic system is causing immense human suffering and inequity. In particular, the poor and most vulnerable are threatened by climate change, although they are not the major cause of the climate problem. He acknowledges the need for believers and non-believers alike to help renew the vitality of Earth’s ecosystems and expand systemic efforts for equity.

In short, he is calling for “ecological conversion” from within all the world religions. He is making visible an emerging worldwide phenomenon of the force of religious environmentalism on the ground, as well as the field of religion and ecology in academia developing new ecotheologies and ecojustice ethics. This diverse movement is evoking a change of mind and heart, consciousness and conscience. Its expression will be seen more fully in the years to come.

The challenge of the contemporary call for ecological renewal cannot be ignored by the religions. Nor can it be answered simply from out of doctrine, dogma, scripture, devotion, ritual, belief, or prayer. It cannot be addressed by any of these well-trod paths of religious expression alone. Yet, like so much of our human cultures and institutions the religions are necessary for our way forward yet not sufficient in themselves for the transformation needed. The roles of the religions cannot be exported from outside their horizons. Thus, the individual religions must explain and transform themselves if they are willing to enter into this period of environmental engagement that is upon us. If the religions can participate in this creativity they may again empower humans to embrace values that sustain life and contribute to a vibrant Earth community.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berry, Thomas. 2009. The Sacred Universe: Earth Spirituality and Religion in the 21st Century (New York: Columbia University Press).

Boff, Leonardo. 1997. Cry of the Earth, Cry of the Poor (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books).

Gottlieb, Roger. 2006. A Greener Faith: Religious Environmentalism and Our Planetary Future . (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Grim, John and Mary Evelyn Tucker, eds. 2014. Ecology and Religion. (Washington, DC: Island Press).

Leopold, Aldo. 1966. A Sand County Almanac . (Oxford University Press).

Rockstrom, Johan and Mattias Klum. 2015. Big World, Small Planet: Abundance Within Planetary Boundaries . (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Schmitz, Oswald. 2016. The New Ecology: Science for a Sustainable World. (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

Taylor, Bron, ed. 2008. Encyclopedia of Religion, Nature, and Culture. (London: Bloomsbury).

Tucker, Mary Evelyn. 2004. Worldly Wonder: Religions Enter their Ecological Phase . (Chicago: Open Court).

Tucker, Mary Evelyn and John Grim, eds. 2001 Religion and Ecology: Can the Climate Change? Daedalus Vol. 130, No.4.

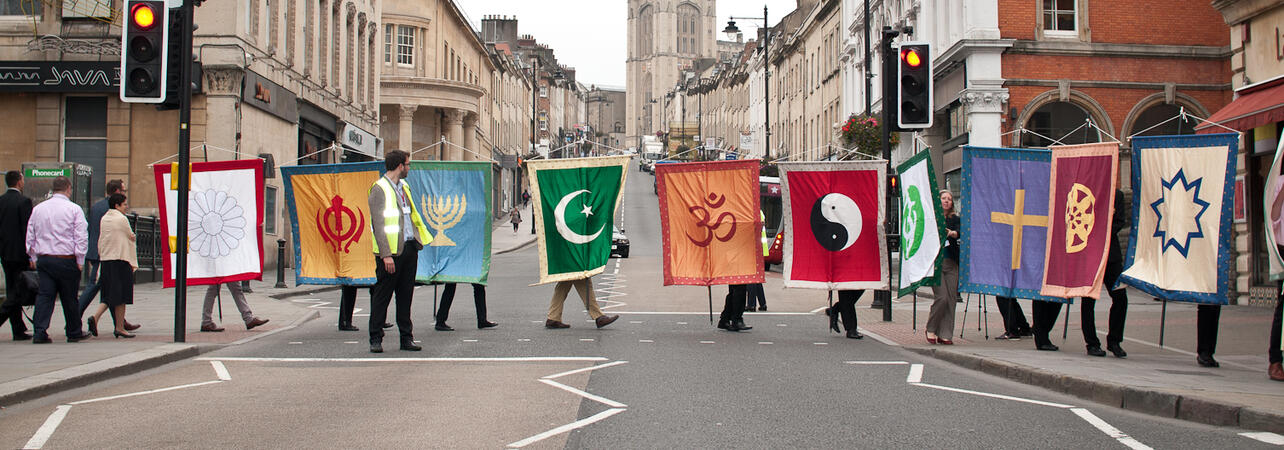

Header photo: ARC procession to UN Faith in Future Meeting, Bristol, UK

The Invention of World Religions by Tomoko Masuzawa

- Post author By Yazid Haroun

- Post date 4th Dec 2020

- No Comments on The Invention of World Religions by Tomoko Masuzawa

How the Modern European Identity is perpetuated through the discourse of World Religions Tweet

The idea of “world religion” expresses a commitment to multiculturalism (i.e. it evinces the multicultural, empathetic spirit of contemporary scholars), presupposing that there are many world religions, and Buddhism and Islam are amongst them. This concept embodies a pluralist ideology, a logic of classification, which has shaped the academic study of religion and, consequently, infiltrated ordinary language. In the past, European scholars of religious studies categorised people of the world into four, well-marked and unevenly portioned, domains: Christians, Jews, Mohammedans, and the rest (heathens, pagans, idolaters, or polytheists). This fourfold schema, which long held sway in early modern compendia and dictionaries, began to crumble in the first half of the nineteenth century, and in the early decades of the twentieth, scholars expanded their understanding of great world religions to eleven: Christianity, Buddhism, Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, Confucianism, Taoism, Shinto, Zoroastrianism, Jainism, and Sikhism. This list became the new unchallenged and taken-for-granted schema. It ran along by force of habit, by force of conventional opinion. With the lapse of time, it became stronger and stronger––must eventually be a fact, a reality not easily destroyed.

To most scholars, the expansion of the list is free of any commitment to exclusivism and actuated not by greed, but by an insatiable love for diversity. It embodies a movement from exclusion to inclusion, or toward religious pluralism, a movement made possible by the increasingly more accurate and specific state of empirical knowledge. Such a train of thought celebrating the achievements of modern knowledge may also lead the presumption that the stability of world religions list today––accompanied by a standard description of each religion––is simply a consequence of better science. If there is a convention to list numerous world religions, may it not be because there are many major religions in the world, together with countless other minor traditions that may be called “others”?

For Tomoko Masuzawa, Western values determined the outcome of the schema, despite the appearance of pluralism. She therefore tries to demonstrate how European universalism perpetuates itself through the discourse of “world religions”. Her aim is not to understand how the field of religious studies emerged in the nineteenth century, but how the discourse on “religions” played a role in the discursive formation of the “West”. She argues that despite the tolerance seemingly epitomised by “world religions”, this concept ironically operates to preserve the uniqueness and superiority of Christianity. This novel discourse is instrumental in the collapse of the old-four ordering system, and also in the eventual rise of the new system, which appears as no more than a pluralism of “world religions”. Thus, she firmly denies that the “advent” of world religions marks “a turn away from the Eurocentric and Eurohegemonic conception of the world, toward a more egalitarian and lateral delineation” (Masuzawa, 2005, p. 13).

This book studies what took place to produce this change, looking into ideas, contentions, and spiritual turmoil disguised beneath the placid pluralism of world-religion discourse. It tries to uncover the origin and function of the idea of “world religions”. For over a century, this idea has had major implications on the fundamental teaching and analysis framework of non-Christian religions in the West. Thus, the book focuses on a particular aspect of the formation of modern European identity, i.e. how Europe came to self-consciousness: Europe as the harbinger of universal history.

With a particular focus on the relation between the comparative study of language and the nascent science of religion, this book shows how in the nineteenth century new classifications of language and race gave special significance to Buddhism and Islam, placing them in opposing categories, the former as Aryan and the latter as Semitic. Christianity, a European faith of Semitic origin, was cast as the “uniquely universal” religion of freedom, while Islam was represented as the outcome of a rigidly ethnic religion of the Arabs imposed upon nations on a semi-global scale. The grouping together of “great religions” was, therefore, intended to highlight the uniqueness of Christianity, which alone achieved universality and transcendence. It was intended to show differences, not similarities: “comparative theology would not compromise the unique and exclusive authority of Christianity” (Masuzawa, 2005, p. 81). The retention of such given superiority faced one critical obstacle: the emergence of the linguistic divide between Indo-European and Semitic languages. Linguistic families were racial categories, as the synonym for Indo-European––Aryan––attests, but since Christianity evolved out of Judaism, and Hebrew is a Semitic language, was Christianity not thereby a Semitic rather than an Indo-European religion, culture, and race? Masuzawa shows that Christianity was detached from Judaism and regrouped with Hellenism.

Masuzawa questions the assertion that the scientific or objective study of religion must be separated from the religious commitment of scholars. In this respect, she directly challenges those who write on the history of modern religious studies. For example, she addresses the rapid inclusion of Buddhism in the canon of world religions and the deep resistance to Islam. The inclusion of Buddhism was made possible by the rise of analysis of Indo-European languages, since the Romantic age. The idea of Indo-European family of languages originated in India. It spread over to Asia and eventually to Europe, particularly to Greece, where a similar analysis emerged and linked Greek civilisation, and hence the European, to India, the home of Buddhism. Thus, Buddhism was a precursor to European civilisation and informed that civilisation, and on these and other grounds, many scholars came to see Buddhism as a great world religion.

Although European scholars had always been hostile to Islam, this image changed during the nineteenth century, and, as a result, Islam was categorised as a Semitic religion. Arabic, like Hebrew, was a non-infected language (unlike Indo-European), and neither was deemed capable of intellectual subtleties as the Indo-European languages. By the end of the nineteenth century, Islam came to be seen as a national religion (Arabic religion, or the religion of the Arabs) rather than a world religion.

Masuzawa suggests that the actual historical process that gave rise to the current epistemic regime was different from the “just-so” claimed story. The process of reshuffling the old schema was, in fact, part of a much broader and fundamental transformation of European identity. The influential new science of comparative philology, a disciple whose significance transcended the technical examination of language, facilitated this change. The discovery of language families or language groups opened “new possibilities for European scholars to reconstruct their ancestral roots, realigning their present more directly with pre-Christian antiquity” (Masuzawa, 2005, p. xii). They precisely located the genealogical origin of European ancestry in the imagined glory, allegedly “timeless” modernity, of ancient Greece, but also found a root of even greater antiquity, the hitherto unknown past of the so-called proto-European progenitors.

An implication of this new mode of thought, supposed by the philological scholarship, was that among the spiritual and cultural legacy of Europe (reconstructed as the “West”), Christianity alone is of Semitic origin. This idea rendered Christianity at odds with Islam and Judaism unless it could be shown to be more Hellenic than Biblical. The idea of Aryan Christianity excited numerous scholars, so much that there appeared several successful treatises in the latter half of the nineteenth century that the supposedly true origin of Christianity, a religion qua Europe, should not be sought in the Hebrew Bible but in some late Hellenic, possibly Indo-Persian or even Buddhist traditions. Concomitant with this urge to Hellenize and Aryanize Christianity was a desire to Semitize Islam. Thenceforward, Islam was rigidly stereotyped as the religion of the Arabs, a bigoted religion rooted in Arab’s national, ethnic, and racial particularities. Scholars insisted on such semitization, despite a fact well known to Europe, namely, that the vast majority of Muslims, then as now, were not Arabs. Thus, Islam cam to stand as the epitome of the racially and ethnically constrained, nonuniversal religion.

With the idea of the possibly “mixed” heritage of Europe, there comes an assessment of collateral effects, an intriguing question hitherto unimaginable: Should monotheism––the doctrine of a single universal god––remain the basic assumption of universality? The answer is also hitherto unimaginable: monotheism is something rather mellifluously philosophical and abstract, one which embodies the principle of unity and universality, but not an absolute authority of a creator. After all, was it not reason––a faculty fully and initially realised purportedly by the Greeks––that allowed the ancients to discern the true unity of this phenomenon? Was it not this discernment, as some hellenzing enthusiasts suggested, that became the foundation of science, the best system of governance, and art, the bona fide universals of the True, the Good, and the Beautiful? In contrast, monotheism, cast as a Semitic tendency, was linked with exclusivity––the rejection of multiplicity––rather than universality––the orderly embrace of a multitudinous totality. It is therefore not surprising the old classification scheme, which saw the old alliance of Abrahamic religions, began to break down under the mounting pressure of these new thoughts, and out of the ruins of this ancient system soared a new conception of Christian Europe––or of European modernity with or without Christianity––with the rest of the world reshuffled eventually to settle into a new map.

Shortcomings

Masuzawa’s book gives rise to several questions: Why did the concept of “world religion” prevail if the aim was to preserve the uniqueness of Christianity? Would the retention of the term indicate retention of its original use? Does the use of the term in academia evince the thinking of scholars? Why not employ the term, if it is the case that some religions, more than others, do transcend national and regional boundaries? Does Masuzawa then attach in general too much importance to terms? Is she under the illusion that words effect great results? However, and as a matter of fact, terms are, as a rule, the shallowest portion of all the arguments. They but dimly represent the tremendous surging desires that lie behind.

The book’s master thesis is complicated by many interesting sub-theses, such as (1) the initial reluctance on the part of European scholars to assign “world religion” status to Islam; (2) the presentation of Islam as “Arab-oriented” and the attempt to desemitize or to Aryanize Christianity; (3) the suggestion that Buddhism first propelled the notion of “world religion” into a pluralistic context; (4) the links between philological discussions of “inflected languages” and geopolitical evaluation of entire civilisations. All these deserve careful and further examination. Nevertheless, most of these strands are linked with strategies used to maintain the universalist claims of Christianity, and this will lead the reader to emphasise Christianity as a target for critique. The possible variant readings of the book’s thesis are unfortunate, for they undermine the book’s underlying claim, viz. that European exceptionalism is promoted through a sustained and uncritical use of the concept of “world religions” (see a detailed discussion in King, 2008).

Masuzawa presents her book as distinctly about European identity, or about how the discourse of world religions preserves the hegemony of European universalism in the face of collapsing claims about Christian exclusivism. However, she only focuses on the Anglophone literature, British and American, thereby giving rise to some vexing enquiries about the identity in question. Is the American identity subsumed into the European without discussion of the many ways Americans defined themselves against Europe? Though it clearly states that the discourse of world religions emerged in an American academic context, its empirical date is firmly rooted in a European rather than a more broadly Euro-American account. If the discourse of world religion arrived into North American colleges and universities in the 1920s and 30s, how is it adequately told under the moniker of European identity? If this is “very much an American phenomenon”, then why not engage with scholarship on American religious and cultural pluralism, such as those notable and immediately obvious sources as David Hollinger and William Hutchison? The lack of discussion on Americans not only undermines the force of the master thesis but may also convey the impression that this is a peculiarly European rather than a Euro-American issue.

Still, the book prompts further questions: Why is the concept only now under careful examination in the Academy? What sort of market forces has made it less of a taboo to explore? What conditions have led to the unveiling of the “world religions” paradigm to take place now at the beginning of the 21 st century? Does not the slow demise of the “world religions” approach reflect a shift of emphasis away from the study of cultural meta-narratives and universalist ideologies, and towards greater recognition of the internal pluralities within such traditions? Indeed, there is a growing interest in eclectic forms of “spirituality” (see Carrette & King, 2005) in certain parts of the Northern Europe and North American academy, thereby a shift away from an emphasis on “traditions” and “religions”. This shift may also reflect an institutional movement in the Academy towards increasing specialisation of knowledge. As such, it is increasingly difficult, if not impossible, to claim specialisation in an entire “world religion”, let alone in all world religions, despite many still to do so where specialisation is limited.

Carrette, J., & King, R. (2005). Selling spirituality: The silent takeover of religion . Routledge.

King, R. (2008). Taking on the Guild: Tomoko Masuzawa and The Invention of World Religions. MTSR Method & Theory in the Study of Religion , 20 (2), 125–133.

Masuzawa, T. (2005). The invention of world religions or, How European universalism was preserved in the language of pluralism . University of Chicago Press.

[Friday 16 th October 2020, Durham]

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- The Impact of Religion in Society Words: 643

- Religion and its Role in the Society Words: 1453

- Religion as a Belief System: What Is It? Words: 1286

- Impact of Religion on Individuals, Society, and the World Words: 556

- Religion and Belief: Comprehensive Review Words: 2504

- Analysis of Christianity as a World Religion Words: 2285

- The Different World Religion Summary Words: 1422

- Major World Religions Before the 16th Century: Common Aspects and Differences Words: 591

- Researching Religion in America Words: 656

- Judaism and Christianity as Revelational Religions Words: 824

- Science and Religion: Historical Relationship Words: 2500

- “Introduction to World Religion” and “How to Study Religion” Words: 601

- American Religion Now and Then Words: 2764

- God Concept in Christianity and Buddhism Religions Words: 563

Core Beliefs and Practices of Major World Religions: Origins and Impact

Origins and development.

Judaism is a monotheistic religion that was founded by Abraham (who was the first to be commanded by God) and Moses (who was also guided by Him as he led the God’s Chosen People from Egypt) (Davis & Velaidium n.d.). As pointed out by Karkra (2012), the majority of major religions have originated in Asia, and Judaism is not an exception. There are variations of Judaism; also, it is the “parent” faith for other Abrahamic monotheistic religions: Christianity and Islam (Karkra 2012, p. 48; Van Voorst 2008, p. 8).

Core Beliefs

The primary texts of Judaism are the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament, Tanakh), the Mishnah, and Talmud (Van Voorst 2008). They believe that their God (Yahweh) had created a perfect world and provided people with things they need, including freedom, but people proceeded to misuse this gift repeatedly, which led to punishments, although God keeps giving people new chances. The Fall of Adam and Eve is an example of abusing the freedom to try the Forbidden Fruit, which gave people an understanding of good and evil. It also led to the establishment of the idea that the woman is to be subservient to the man since it was Eve who convinced Adam to eat the fruit.

The Jewish consider themselves to be the “God’s Chosen People,” which defines the strong connection between religion and nationality (Davis & Velaidium n.d., p. 7). Their God is powerful and loving, and he has revealed himself on numerous occasions by helping the Jewish (for example, in Exodus). As a result, they have a “corresponding responsibility,” that is, God and the Jewish have a covenant. In order to fulfill their duties, humans are expected to follow the law, Torah, which is presented in Tanakh and summarized in the Ten Commandments. Naturally, this law does not prevent the Jewish from the development of secular law or from being subject to the law of the country they have chosen to live in (Karkra 2012).

The idea of Messiahs as people burdened with a glorious purpose was also developed in this religion (Davis & Velaidium n.d., p. 46). Jesus is an example of the Messiah and a key figure of another religion, Christianity.

Central Practices

The main festivals of Judaism include the weekly Sabbath (the Saturday that is reserved for resting as was done by the God after the creation of the world), and a number of annual festivities. For instance, the New Year is Judaism is called Rosh Hashanah, and it should be used for praying and repenting. Another example is Sukkot, a holiday in the name of the days that the Jewish had spent in the desert while walking towards the promised land (Robinson 2008, pp. 93-95, 101-102).

Apart from that, Judaism, like most religions, involves celebrations for the key milestones of a human’s life (birth, marriage, death). An important custom in Orthodox and Conservative Judaism sets a particular restriction on the nationality of the Jewish: only the people who are born to a Jewish mother are considered Jews. In Reform Judaism, being born to a Jewish father is sufficient (Karkra 2012).

Christianity

Christianity also originated in the Middle East, and it is similar to Judaism in being monotheistic and using the Tanakh, which is called the Old Testament in this religion. However, religions are still very distinct. Christianity is not exactly homogenous, and its three biggest branches include the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Christianity, and Protestantism. The first two are similar in the power that is entrusted to the Church while Protestant Christianity refuses idolatry (like icons) and focuses on the faith of an individual (Davis & Velaidium n.d.).

The central scripture of the religion is the Bible. It includes the Old and the New Testaments; the Ten Commandments and Gospel are the “divine revelations” (Karkra 2012).

The central figure of Christianity is Jesus Christ, who is believed to be both fully human (Jesus of Nazareth, who lived as a human, was incarnated) and fully divine (Jesus Christ, the savior of humans and the God the Son). He saved the humanity through the Atonement (his own death), which has allowed healing the separation of people from the God that happened as a result of our selfishness and the Original Sin (eating the forbidden fruit). Also, it is important that the God in Christianity is represented through the Trinity: the Father (the creator of the world), the Son (Jesus Christ), and the Holy Spirit (spiritual energy that “can motivate people to turn to Christ”) (Davis & Velaidium n.d., p. 59).

Just like Judaism, Christianity follows the key milestones in a person’s life. An example of a specific custom is baptism: it is concerned with accepting a new member into the Church. Among religious people, it is done with very young children, even though the New Testament does not mention infant baptism, and some of the Christians believe that one must realize being accepted to Christianity (Lopez 2010, p. 205). Apart from that, central practices of the religion include the worship of their God, which involves the Sunday gatherings in churches with specific rituals and praying.

Confucianism

Confucianism is a religion and philosophy. It began with the teaching of Kung Fu-Tzu; this name can be translated as “Master Kund,” but the Western people changed it to Confucius. The man lived between 551-479 BC (Van Voorst 2008, p. 139). Confucianism was also developed by Mencius (Meng-Tzu) and, naturally, the religion has been changing and developing just like the previously mentioned ones (Gardner 2015).

Confucianism is different from the two relatively similar Abrahamic religions because it focuses on humans’ ability to do good rather than their aptitude to sin. There is a number of concepts in the religion that should be discussed. Ren (human kindness) can be interpreted as the belief that compassion and kindness make humans human. However, humanness needs to be nurtured, and one of the key ideas of Confucianism describes the necessity for self-development. As a result, the typical distinction between secular and sacred gets blurred in Confucianism since the cultivation of goodness is not reserved for the saint or the priests (Gardner 2015). Also, Confucianism upheld the ideal of education being accessible to all who are willing to learn (Van Voorst 2008, p. 142).

Apart from that, Confucianism is concerned with the ideas of yin-yang balance, Dao (the way), Zhi (the desire to learn), Yi (the proper, moral conduct), and some others. There is no Confucianism God in the traditional sense of the world, but the self-improvement is aimed at reaching the unity with Tian, which can be interpreted as the God (or the Universe) (Van Voorst 2008, pp. 13-14).

The practices of Confucianism include li that denotes ceremonies, which are meant to express ren. They are aimed at fostering the spiritual growth of humans rather than appeasing immortal beings, which is in line with the beliefs of Confucianism. Another important practice, which has been attracting the attention of medical professionals due to its potential of improving health (Mars & Abbey 2010), is meditation (Davis & Velaidium n.d.).

This introduction to the three religions cannot encompass all of their specifics, but it allows a glimpse into their similarities and differences.

Reference List

Davis, PG & Velaidium, J n.d., World Religions.

Gardner, D 2015, Confucianism, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Kakra, B 2012, The origin of religions , AuthorHouse, Bloomington, IN.

Lopez, K 2010, Christianity , Mercer University Press, Macon, Ga.

Mars, TS & Abbey, H 2010, Mindfulness meditation practice as a healthcare intervention: A systematic review’, International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine , vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 56-66.

Robinson, G 2008, Essential Judaism , Pocket Books, New York, NY.

Van Voorst, R 2008, Anthology of world scriptures , Thomson Wadsworth, Australia.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2020, November 4). Core Beliefs and Practices of Major World Religions: Origins and Impact. https://studycorgi.com/world-religions-origins-core-beliefs-and-practices/

"Core Beliefs and Practices of Major World Religions: Origins and Impact." StudyCorgi , 4 Nov. 2020, studycorgi.com/world-religions-origins-core-beliefs-and-practices/.

StudyCorgi . (2020) 'Core Beliefs and Practices of Major World Religions: Origins and Impact'. 4 November.

1. StudyCorgi . "Core Beliefs and Practices of Major World Religions: Origins and Impact." November 4, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/world-religions-origins-core-beliefs-and-practices/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Core Beliefs and Practices of Major World Religions: Origins and Impact." November 4, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/world-religions-origins-core-beliefs-and-practices/.

StudyCorgi . 2020. "Core Beliefs and Practices of Major World Religions: Origins and Impact." November 4, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/world-religions-origins-core-beliefs-and-practices/.

This paper, “Core Beliefs and Practices of Major World Religions: Origins and Impact”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: November 28, 2024 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Essay on World Religions And Belief Systems

Students are often asked to write an essay on World Religions And Belief Systems in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on World Religions And Belief Systems

World religions.

There are many different religions in the world, each with its own beliefs and practices. Some of the major religions include Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Judaism.

Belief Systems

A belief system is a set of beliefs that a person or group of people holds to be true. Belief systems can be religious or secular. Religious belief systems are based on the teachings of a particular religion, while secular belief systems are not based on any particular religion.

Diversity of Religions

The diversity of religions in the world is a reflection of the different ways that people have tried to understand the meaning of life and the universe. There is no one right way to believe, and people should be free to practice the religion that they feel is right for them.

It is important to be tolerant of people who have different religious beliefs. Tolerance means respecting the beliefs of others, even if you do not agree with them. Tolerance is essential for creating a peaceful and harmonious world.

250 Words Essay on World Religions And Belief Systems

What are world religions.

World religions are belief systems that have a large number of followers all over the world. They offer rituals, ceremonies, and practices to help people connect with the divine or ultimate reality. World religions include Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Judaism.

Christianity:

Christianity is based on the teachings of Jesus Christ and revolves around the belief in a triune God consisting of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Christians believe that Jesus is the Messiah who came to Earth to save humanity from sin. Christianity emphasizes love, forgiveness, and compassion.

Islam is founded on the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad and centers around belief in one God, Allah, and his messenger, Muhammad. It highlights the importance of submission to God’s will, known as Islam, and adherence to the Five Pillars of Islam. Muslims strive to live a life of devotion, prayer, fasting, charity, and pilgrimage to Mecca.

Hinduism is a complex and diverse belief system with no single founder. It originated in India and encompasses a variety of traditions, philosophies, and practices. Hinduism places great emphasis on dharma, or righteous living, and the concept of reincarnation, where the soul passes through a cycle of birth, death, and rebirth.

Buddhism, founded by Siddhartha Gautama, or the Buddha, originated in India and focuses on the pursuit of enlightenment or nirvana. It emphasizes the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path as ways to overcome suffering and achieve liberation from the cycle of rebirth.

Judaism is the oldest monotheistic religion, dating back to the Hebrew patriarchs, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. It revolves around the belief in one God, Yahweh or Jehovah, and the sacredness of the Torah, the Hebrew Bible. Judaism emphasizes ethical behavior, ritual observance, and the covenant between God and the Jewish people.

500 Words Essay on World Religions And Belief Systems

World religions are belief systems that have a large number of followers all over the world. They often have a long history, and they have shaped the cultures of the regions where they are practiced. Some of the largest world religions include Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism.

Belief Systems of World Religions

Belief systems of world religions are the sets of beliefs and practices that are followed by the members of that religion. These beliefs and practices can be about things like God or gods, the afterlife, and the meaning of life. They can also include things like rituals, ceremonies, and festivals.

Similarities among World Religions

Even though world religions have different beliefs and practices, they also share some similarities. For example, many religions believe in a higher power, or God. They also often have a sense of community and belonging. Additionally, many religions have a code of ethics that their members are expected to follow.

Differences among World Religions

Of course, there are also many differences among world religions. These differences can be in their beliefs about God, the afterlife, and the meaning of life. They can also be in their rituals, ceremonies, and festivals. These differences can sometimes lead to conflict between different religious groups.

Importance of Understanding World Religions

It is important to understand world religions because they play a major role in the lives of many people around the world. They can help to shape people’s values, beliefs, and behaviors. They can also give people a sense of community and belonging. By understanding world religions, we can better understand the people who practice them and build bridges between different cultures.

World religions are belief systems that have a large number of followers all over the world. They often have a long history, and they have shaped the cultures of the regions where they are practiced. Belief systems of world religions are the sets of beliefs and practices that are followed by the members of that religion. They can be about things like God or gods, the afterlife, and the meaning of life. Even though world religions have different beliefs and practices, they also share some similarities.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Refugee

- Essay on Power Of Truth

- Essay on Young India Boon Or Bane

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The Parliament of World Religions has included panels on this topic since 1998 and most expansively in 2015. Since 1995 the UK based Alliance of Religion and Conservation (ARC), led by Martin Palmer, has been doing significant work with religious communities around under the patronage of Prince Philip.

But the major world religions I know of — Hinduism, Judaism, Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam — were bigger than a single city or even a single region of the world. In fact, all of these religions developed around the same time and all of them have survived for thousands of years.

Dec 4, 2020 · King, R. (2008). Taking on the Guild: Tomoko Masuzawa and The Invention of World Religions. MTSR Method & Theory in the Study of Religion, 20(2), 125–133. Masuzawa, T. (2005). The invention of world religions or, How European universalism was preserved in the language of pluralism. University of Chicago Press. [Friday 16 th October 2020, Durham]

Jul 17, 2018 · 4. IMPORTANT DATES ON THE ORIGIN OF WORLD RELIGIONS DATE SIGNIFICANCE c. 2000 BCE Time of Abraham, the patriarch of Israel c. 1200 BCE Time of Moses, the Hebrew leader of Exodus c. 1100 – 500 BCE Hindus compiled their holy texts, the Vedas c. 563 – 83 BCE Time of the Buddha, founder of Buddhism c. 551 – 479 BCE Time of Confucius, founder of Confucianism c. 200 BCE The Hindu book ...

Religion is a fundamental element of human society. It is what binds a country, society or group of individuals together. However, in some instances it destroys unity amoungst these. Religion is a belief in a superhuman entity(s) which control(s) the universe. Every religion has its differences but most strive for a just life and the right morals.

and Islam — were bigger than a single city or even a single region of the world. In fact, all of these religions developed within a few hundred years. By now, they have survived for thousands of years. It seems that people have had local religions since early times. Why did several important global religions emerge between 1200 BCE and 700 CE?

Medieval world religions. World religions of the present day established themselves throughout Eurasia during the Middle Ages by: Christianization of the Western world; Buddhist missions to East Asia; the decline of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent; the spread of Islam throughout the Middle East, Central Asia, North Africa and parts of ...

Core Beliefs. The primary texts of Judaism are the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament, Tanakh), the Mishnah, and Talmud (Van Voorst 2008). They believe that their God (Yahweh) had created a perfect world and provided people with things they need, including freedom, but people proceeded to misuse this gift repeatedly, which led to punishments, although God keeps giving people new chances.

World Religion Essay. Danielle Walker World Religions Field Trip Paper 4 May 2014 Different People’s Way of Life Many individuals abide or live life along a set of guidelines or follow a certain religion and that conveys their way of life. Religions have many values, beliefs, and aspirations among them.

Feb 18, 2024 · Students are often asked to write an essay on World Religions And Belief Systems in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.