Health Research Policy and Systems

Aims and scope.

Health Research Policy and Systems covers all aspects of the organisation and use of health research – including agenda setting, building health research capacity, and how research as a whole benefits decision makers, practitioners in health and related fields, and society at large.

Discount for Health Systems Global members

All Health Systems Global members receive a 20% discount on Health Research Policy and Systems Article Processing Charges (APCs). To claim the discount, please contact the Secretariat at [email protected] to obtain the BMC journals' discount code.

- Most accessed

The embedded research model: an answer to the research and evaluation needs of community service organizations?

Authors: Bianca E. Kavanagh, Vincent L. Versace and Kevin P. Mc Namara

Implementation of national policies and interventions ( WHO Best Buys ) for non-communicable disease prevention and control in Ghana: a mixed methods analysis

Authors: Leonard Baatiema, Olutobi Adekunle Sanuade, Irene Akwo Kretchy, Lydia Okoibhole, Sandra Boatemaa Kushitor, Hassan Haghparast-Bidgoli, Raphael Baffour Awuah, Samuel Amon, Sedzro Kojo Mensah, Carlos S. Grijalva-Eternod, Kafui Adjaye-Gbewonyo, Publa Antwi, Hannah Maria Jennings, Daniel Kojo Arhinful, Moses Aikins, Kwadwo Koram…

Policy impact of the Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team: global perspective and United Kingdom case study

Authors: Sabine L. van Elsland, Ryan M. O’Hare, Ruth McCabe, Daniel J. Laydon, Neil M. Ferguson, Anne Cori and Paula Christen

Real-world data to improve organ and tissue donation policies: lessons learned from the tissue and organ donor epidemiology study

Authors: Melissa A. Greenwald, Hussein Ezzeldin, Emily A. Blumberg, Barbee I. Whitaker and Richard A. Forshee

What are the priorities of consumers and carers regarding measurement for evaluation in mental healthcare? Results from a Q-methodology study

Authors: Rachel O’Loughlin, Caroline Lambert, Gemma Olsen, Kate Thwaites, Keir Saltmarsh, Julie Anderson, Nancy Devlin, Harriet Hiscock and Kim Dalziel

Most recent articles RSS

View all articles

The utilisation of health research in policy-making: concepts, examples and methods of assessment

Authors: Stephen R Hanney, Miguel A Gonzalez-Block, Martin J Buxton and Maurice Kogan

The application of systems thinking in health: why use systems thinking?

Authors: David H Peters

The role of NGOs in global health research for development

Authors: Hélène Delisle, Janet Hatcher Roberts, Michelle Munro, Lori Jones and Theresa W Gyorkos

How to engage stakeholders in research: design principles to support improvement

Authors: Annette Boaz, Stephen Hanney, Robert Borst, Alison O’Shea and Maarten Kok

The 10 largest public and philanthropic funders of health research in the world: what they fund and how they distribute their funds

Authors: Roderik F. Viergever and Thom C. C. Hendriks

Most accessed articles RSS

Featured article

Identifying priority technical and context-specific issues in improving the conduct, reporting and use of health economic evaluation in low- and middle-income countries

Health Research Policy and Systems (2018) 16 :4

The authors aim to identify the top priority issues that impede the conduct, reporting and use of economic evaluation as well as potential solutions as an input for future research topics by the international Decision Support Initiative and other movements.

Visit our Health Services Research page

Editors-in-Chief

Kathryn Oliver, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK Chigozie Jesse Uneke, Ebonyi State University, Nigeria

New cross journal series

Latest Tweets

Your browser needs to have JavaScript enabled to view this timeline

Call for papers

We are delighted to announce a Call for Papers for our new thematic series on " The role of the health research system during the COVID-19 epidemic: experiences, challenges and future vision ". This will focus on the role of health research systems in the control and management of COVID-19, so that the experiences of countries can be shared with each other and the lessons learned are accessible to all. More details can be found here .

Do you have an idea for a thematic series? Let us know!

Published in collaboration with the World Health Organization

- Editorial Board

- Manuscript editing services

- Instructions for Editors

- Sign up for article alerts and news from this journal

- Follow us on Twitter

Annual Journal Metrics

Citation Impact 2023 Journal Impact Factor: 3.6 5-year Journal Impact Factor: 4.3 Source Normalized Impact per Paper (SNIP): 1.804 SCImago Journal Rank (SJR): 1.563

Speed 2023 Submission to first editorial decision (median days): 67 Submission to acceptance (median days): 196

Usage 2023 Downloads: 1,738,266 Altmetric mentions: 1,598

- More about our metrics

ISSN: 1478-4505

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

PhD in Health Services Research and Health Policy

Doctoral program in health services research and health policy, rollins school of public health department of health policy and management.

The PhD in Health Services Research and Health Policy at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University is a full-time program that trains researchers in the fields of health policy, health economics, health management, and health services research.

Students take doctoral-level classes in the Department of Economics, the Department of Health Policy and Management, the Goizueta business school, and elsewhere throughout the university. Many students also collaborate with faculty on research.

Following the completion of their coursework, students work on their independent research for their dissertation.

What You’ll Learn

Students in our program take classes in one of two tracks: Economics or Organizations and Management .

Economics Track

Students in the Economics track take graduate-level classes in the Department of Economics, alongside students pursing a PhD in economics. The economics track prepares students to apply economic theory to evaluate topics in health and health policy.

Organizations and Management Track

Students in Organizations and Management take advanced and doctoral-level courses in Emory’s Goizueta School of Business. The track prepares students to examine questions pertaining to access, quality, cost of health care and health outcomes. Students in this track will learn how theories and concepts from fields such as organizational behavior and technology management can be applied to medicine and health care organizations.

Core Courses and More

All students in the program take classes in statistical methods, research design, and health policy seminar. Students have room to take electives, which could be any graduate-level class at Emory or nearby universities (Georgia State, Georgia Tech).

What Can You Do With a Graduate Degree in Health Services Research and Health Policy?

The program prepares students for a variety of research-focused careers in academia, think tanks, foundations, government agencies, pharmaceutical firms, and consulting. Graduates are employed at the American Cancer Society, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, Trilliant Health, Flatiron, Carnegie Mellon, Washington University (St. Louis), the Urban Institute, Northwestern University, Harvard Medical School, and Emory Medical School.

We discourage applications from students who view a PhD as a credential or who want to focus exclusively on administration, management, or advocacy. There are other professional degrees that are better suited to those types of careers.

What Type of Research Will You Do in the Health Services Research and Health Policy PhD Program?

Students perform research on a wide variety of topics related to delivery of medical care, insurance, and the determinants of health. Some examples of the papers that students have published from their dissertations include:

Vertical integration of oncologists and cancer outcomes and costs in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer . JNCI 2022. (Xin Hu, Ph.D. 2023)

Evaluating Medicaid Managed Care Network Adequacy Standards And Associations With Specialty Care Access For Children . Health Affairs 2023. (Allison Hu, P.D. 2023)

Heuristics in the delivery room. Science 2021. (Manasvini Singh, Ph.D. 2020)

The effect of Medicaid expansion on crime reduction: Evidence from HIFA-waiver expansions. Journal of Public Economics 2017. (Heifei Wen, Ph.D. 2015)

Effect of Medicaid disenrollment on health care utilization among adults with mental health disorders. Medical Care 2019 (Xu Ji, Ph.D. 2017).

Patterns of use and survival outcomes of positron emission tomography for initial staging in elderly follicular lymphoma patients . Leukemia & Lymphoma 2017 (Ashish Rai, Ph.D. 2015)

Are two heads better than one or do too many cooks spoil the broth? The tradeoff between physician division of labor and patient continuity of care for older adults with complex chronic conditions. Health Services Research 2016. (Kenton Johnston, Ph.D. 2015).

Admissions Requirements

Applicants should provide:

- Complete application

- 3 letters of recommendation

- A transcript from each post-secondary institution you have attended

- Statement of purpose (500-1000 words): Please describe your previous research experiences or training that have led you to apply to this program. Include a discussion of your current research interests, how this program aligns with those interests, and your long-term goals after completing your doctoral degree.

- Graduate faculty identification: Please identify at least two Health Policy and Management Faculty members with whom you are interested in working.

Please note:

- GRE scores are encouraged (The Emory Code for the GRE is 5187)

- TOEFL scores are optional

- Applicants do not need to have a master’s degree

Visit Emory’s Laney Graduate School website to apply now .

You do not need to contact the program or faculty before applying. We give equal attention to all applications, regardless of whether applicants know faculty or have had prior contact with them.

Please contact the director, Ilana Graetz, [email protected] , or the program administrator, Kent Tolleson, [email protected] if you have additional questions.

Key Dates and Info

September 15, 2024 : Application opens for Fall 2024

November 1, 2024, 12:30-1:30 pm ET: Informational webinar

December 1, 2024: Application deadline

February 2025: Offer letters sent to successful applicants

If you would like to learn more about our program, please review our webinarat this link PhD Webinar

Program faculty

Students have wide leeway to work with faculty at any Emory school or department. Most students work with the faculty on the list below.

Department of Health Policy and Management

Kathleen Adams (Ph.D. Economics, University of Colorado) Risk behavior, maternal and child health, insurance coverage, Medicaid policy.

Sarah Blake (Ph.D. Public Policy, Georgia State/Georgia Institute of Technology) Maternal and child health, reproductive health, implementation science.

Janet Cummings (Ph.D. Health Policy, UCLA) Mental health and substance abuse policy.

Benjamin Druss (M.D., New York University) Mental health and substance abuse policy.

Maria Dieci (Ph.D. Health Policy, UC Berkeley) Health economics, global health and development economics.

Laurie Gaydos (Ph.D. UNC Chapell Hill). Mixed-methods, women’s, reproductive, and maternal/child health

Ilana Graetz (Ph.D. Health Policy, UC Berkeley) Health information technology, quality improvement.

David Howard (Ph.D. Health Policy, Harvard) Health economics, reimbursement policy, pharmaceutical markets.

Joseph Lipscomb (Ph.D. Economics, University of North Carolina) Health outcomes assessment and improvement.

Stephen Patrick (MD, Florida State University College of Medicine) Maternal and child health, substance use and prevention, Medicaid, child welfare.

Victoria Phillips (Ph.D. Economics, Oxford) Health economics, cost-effectiveness analysis.

Courtney Yarborough (Ph.D. Public Policy, University of Georgia) Substance abuse policy, pharmaceutical markets.

Affiliated faculty in other departments at Emory

Puneet Chehal (Ph.D. Public Policy, Duke) Department of Family and Preventive Medicine. Medicaid and chronic illness in underserved populations.

Hui Shao (Ph.D. Health Services Research and Economics, Tulane) Pharmacoepidemiology, health economics, and comparative effectinvess.

Xin Hu (Ph.D. Health Policy, Emory) Department of Radiation Oncology. Organizational structure, cancer outcomes, and access to health care.

Xu Ji (Ph.D. Health Policy, Emory) Department of Pediatrics. Health care quality, health outcomes, access to health care.

Dio Kavalieratos (Ph.D. Health Policy, University of North Carolina) Department of Family Medicine and Palliative Care. End-of-life care, implementation science.

Sara Markowitz (Ph.D. Economics, CUNY) Department of Economics. Health economics, labor economics, maternal and child health.

Ian McCarthy (Ph.D. Economics, University of Indiana) Department of Economics. Health economics, industrial organization.

Current PhD Students

Lamont Sutton

Xinyue Zhang

Marissa Coloske

Martha Wetzel

Paul George

Alex Soltoff

Elizabeth Staton

Zhuoqi Yang

Cristian Ramos

- News & Highlights

- Publications and Documents

- Education in C/T Science

- Browse Our Courses

- C/T Research Academy

- K12 Investigator Training

- Harvard Catalyst On-Demand

- SMART IRB Reliance Request

- Biostatistics Consulting

- Regulatory Support

- Pilot Funding

- Informatics Program

- Community Engagement

- Diversity Inclusion

- Research Enrollment and Diversity

- Harvard Catalyst Profiles

Community Engagement Program

Supporting bi-directional community engagement to improve the relevance, quality, and impact of research.

- Getting Started

- Resources for Equity in Research

- Resources for Community Engaged Implementation Science

- Community Advisory Board

- Community Ambassador Initiative

- Community-Engaged Student Practice Placement

- Maternal Health Equity

- Youth Mental Health

- Leadership and Membership

- Past Members

- Study Review Rubric

- News, Podcasts, & Webinars

- Policy Atlas

For more information:

Policy research.

Health Policy research aims to understand how policies, regulations, and practices may influence population health. Translating research into evidence-based policies is an important approach to improve population health and address health disparities.

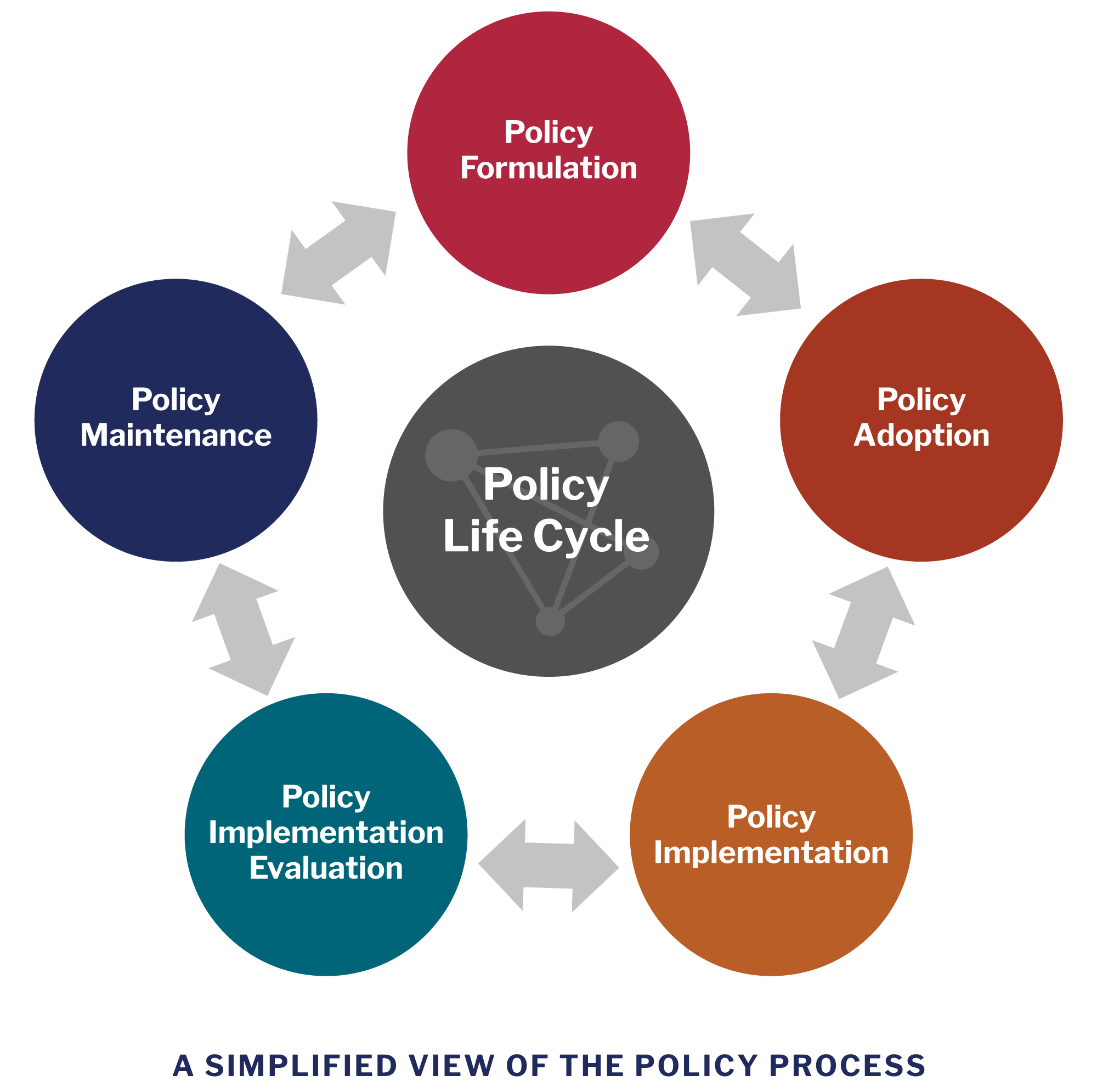

The policy process, although complex and dynamic, provides an opportunity to ask different types of research questions and apply various methodologies – from public health law to health services research to cost-effectiveness to policy implementation and dissemination.

View image description .

Harvard Catalyst Policy Atlas

Policy Atlas is a free, web-based, curated research platform that catalogues downloadable policy-relevant data, use cases, and instructional materials and tools to facilitate health policy research. The Policy Atlas includes data on various health topics and policies, and may be used for research, evaluation, or a quick summary of state rankings or health trends. The topics vary from health laws and bills, to social and environmental determinants of health, to health disparities, and other topics.

Examples of Policy Research

Policy adoption study: Examination of Trends and Evidence-Based Elements in State Physical Education Legislation: A Content Analysis

This study comprehensively reviewed existing state legislation on school physical education (PE) requirements to identify evidence-based policies. The authors found that despite frequent PE bill introduction, the number of evidence-based bills was relatively low.

Policy implementation study: Political Analysis for Health Policy Implementation

To better understand factors that may affect the process and the success of policy implementation, a political analysis was conducted to identify stakeholder groups that are likely to play a critical role in the process. The results revealed that six groups impact the implementation process: interest groups, bureaucratic, budget, leadership, beneficiary, and external actors.

Policy impact evaluation: Reducing Disparities in Tobacco Retailer Density by Banning Tobacco Product Sales Near Schools

This study examined whether a policy ban on tobacco product sales near schools could reduce existing socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in tobacco retailer density in Missouri and New York. The findings suggested that the policy ban would reduce or eliminate existing disparities in tobacco retailer density by income level and by proportion of African American residents.

Other Resources

Health Policy Analysis and Evidence : Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) resource on health policy analysis and evidence-driven policy to improve population health.

Health in All Policies (American Public Health Association) : a policy approach to address social and other factors that influence health and equity.

Four-Part Webinar Series on Policy Evaluation (National Collaboration on Childhood Obesity Research) : This seminar series aims to increase skills of researchers and practitioners in policy evaluation effectiveness.

Research Tools (Center for Health Economics and Policy, Washington University in St. Louis) : health economics and policy research tools, including cost effectiveness, policy analysis toolkit, and policy analysis web series.

Theory & Methods (Center for Public Health Law Research) : public law/ legal epidemiology methods for conducting research on the impact of laws and legislation on public health.

Introduction to Legal Mapping (ChangeLab Solutions) : an introduction to legal mapping, a method to determine what laws exist on a certain topic, collect and summarize policy data, and ultimately estimate the effects of these policies on health outcomes.

The Methods Centers at Pardee RAND Graduate School : a resource on research methods for conducting policy research, including qualitative and mixed methods, decision making, causal inference, decision making and data science and gaming approaches.

View PDF of the above information.

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Bridging Public Health Research and State-Level Policy: The Texas Research-to-Policy Collaboration Project

IMPLEMENTATION EVALUATION — Volume 21 — November 7, 2024

Deanna M. Hoelscher, PhD, RDN, LD, CNS 1 ,2 ; Alexandra van den Berg, PhD, MPH 1 ,2 ; Amelia Roebuck, PhD 1 ,2 ; Shelby Flores-Thorpe, PhD, MEd, CHES 1 ,2 ; Kathleen Manuel, MPH 1 ,2 ; Tiffni Menendez, MPH 1 ,2 ; Christine Jovanovic, PhD, MPH 3 ; Aliya Hussaini, MD, MSc 4 ; John T. Menchaca, MD 5 ; Elizabeth Long, PhD 6 ; D. Max Crowley, PhD 6 ; J. Taylor Scott, PhD 6 ( View author affiliations )

Suggested citation for this article: Hoelscher DM, van den Berg A, Roebuck A, Flores-Thorpe S, Manuel K, Menendez T, et al. Bridging Public Health Research and State-Level Policy: The Texas Research-to-Policy Collaboration Project. Prev Chronic Dis 2024;21:240171. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd21.240171 .

PEER REVIEWED

Introduction

Purpose and objectives, intervention approach, evaluation methods, implications for public health, acknowledgments, author information.

What is known on this topic?

Although evidence-based policy can lead to better community health outcomes, public health researchers need support and resources to communicate their work to policymakers.

What is added by this report?

This project describes the state-level adaptation of a federal model that links researchers with policymakers to accelerate the implementation of evidence-based public health policy.

What are the implications for public health practice?

The Texas Research-to-Policy Collaboration Project determined emerging health priorities for the state legislative session and developed communication strategies and resources to link researchers with policymakers.

Significant barriers to the implementation of evidence-based policy exist. Establishing an infrastructure and resources to support this process at the state level can accelerate the translation of research into practice. This study describes the adaptation and initial evaluation of the Texas Research-to-Policy Collaboration (TX RPC) Project, focusing on the adaptation process, legislative public health policy priorities, and baseline researcher policy knowledge and self-efficacy.

The federal Research-to-Policy Collaboration (RPC) method was adapted to the Texas legislative process in 2020. Policymakers and public health researchers were recruited using direct outreach and referrals. Legislators or their aides were interviewed to determine health policy needs, which directed the development of legislator resources, webinars, and recruitment of additional public health researchers with specific expertise. Researchers were trained to facilitate communication with policymakers, and TX RPC Project staff facilitated legislator and researcher meetings to provide data and policy input.

Baseline surveys were completed with legislators to assess the use of health researchers in policy. Surveys were also administered before training to researchers assessing self-efficacy, knowledge, and training needs. Qualitative data from the legislator interviews were analyzed using inductive and deductive approaches. Quantitative survey data were analyzed using descriptive statistics for scales and individual survey items.

Legislative offices (n = 21) identified health care access, mental health, and health disparities as key health issues. Legislators reported that health data were important but did not actively involve researchers in legislation. Researchers (n = 73) reported that policy informed their work but had low engagement with legislators. Researcher training surveys indicated lower policy self-efficacy and knowledge and the need for additional training.

Adaptation of the RPC model for state-level health policy is feasible but necessitates logistical changes based on the unique legislative body. Researchers need training and resources to engage with policymakers.

Although it is well accepted that nonmedical drivers of health or social determinants of health, such as housing, food insecurity, and transportation, exert significant effects on population health (1–3), recent scholars have begun to look further upstream at political determinants of health (4). Political determinants of health can be defined as the forces that reinforce or influence environmental or system-level factors that either exacerbate or attenuate health equity (4). These determinants, which include voting, government, and policy, are the forces that shape the environmental or systemic factors influencing health equity, either exacerbating disparities or contributing to their mitigation (4). Recognizing the critical interplay between civic participation and health, Healthy People 2030 has set a national health objective to increase the proportion of voting-age citizens who participate in elections (5). This acknowledgment underscores the importance of engaging with political determinants of health as a means to advance evidence-based health policies, highlighting a focus for health professionals aiming to improve health outcomes by bridging the gap between research findings and policy implementation.

Bridging the gap from health research to policy implementation remains a serious challenge, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers and policymakers have historically operated in distinct spheres with minimal collaboration (6). This separation is compounded by factors such as differing political structures, cultural beliefs and values, and the inherent trade-offs between costs and benefits, which introduces uncertainty into the process of advancing health policies at the population level. Further, the decision-making processes of researchers and policymakers are notably different and may hamper the connection and collaboration between the 2 groups (6,7). Researchers tend to engage in discrete, planned projects, whereas policymakers navigate a shorter, unplanned flow of tasks, often responding to immediate needs and unforeseen events. The difference in approach results in researchers needing time to collect or compile data to provide evidence-based recommendations, whereas policymakers must often make quick decisions, which are not always grounded in the empirical data that researchers value. Instead, policymakers may resort to rapidly acquired information, which may lack credibility. Recognizing and addressing these operational differences can enhance the translation of research into practice. Such efforts could substantially improve the effectiveness of public health policies and influence political determinants of health (8).

Even acknowledging the challenges and differences in operations between researchers and policymakers as a fundamental barrier, translation from research to policy is further complicated by additional and substantial barriers. Numerous studies have explored the mechanisms and challenges to better link research and policy (9–12). Caplan’s “two-communities” theory (13) from 1979 suggests that differing priorities, languages, and reward structures cause the gap between research and policy. Other barriers in translating research to policy include few direct interactions between policymakers and researchers, a lack of trust between policymakers and researchers, the perception that research is untimely or irrelevant, divergent communication styles, conflicting priorities, and budgetary pressures (8,10–12). This body of research emphasizes the importance of personal engagement and trusting relationships between researchers and policymakers to transfer research to policy effectively (14). Further, it underscores that these relationships are both timely and sensitive to the constraints policymakers face (15).

In response to these persistent barriers, recent initiatives have aimed to provide practical guidance for researchers to more effectively bridge the gap between research and policy. Haynes et al conducted a qualitative analysis of Australian civil servants (16) that identified 3 key attributes of researchers that policymakers particularly value: competence, integrity, and benevolence. Similarly, Oliver and Cairney’s (17) systematic review builds on this perspective by outlining a strategic framework for academic engagement in the policy process, emphasizing delivering high-quality research, fostering relationships with policymakers, and defining a clear stance as either a committed advocate or a neutral “honest broker.” Furthermore, there is growing consensus that a more sophisticated, bi-directional model enhances researchers’ ability to communicate findings, adapt projects to meet policy-relevant research questions, and understand organizational advocacy guidelines, while also encouraging policymakers to proactively engage with researchers ahead of legislative windows and offer political insights for selecting achievable policy-informed research objectives. This reciprocal relationship hinges on the establishment of trusted partnerships wherein researchers serve as honest brokers — an objective resource for navigating the complexities of policymaking (18,19).

Leveraging the insights from this body of research, the Research-to-Policy Collaboration (RPC) model was developed to facilitate personal researcher–policymaker relationships at the federal level and support the generation of timely and relevant evidence materials. A pilot study (7,20) of the RPC model was conducted, focusing on criminal justice policy efforts at the federal level. The aim of the study was to determine the effects on legislative–researcher connections and legislator and prevention scientist engagement, in addition to the cost-effectiveness of this approach. Ten Congressional offices participated in the pilot, which was conducted over 230 days. Results illustrated the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of this model for fostering personal connections between researchers and policymakers at the federal level. The study also highlighted that the most common legislative requests involved reviewing preventive intervention strategies (37%) and summarizing etiologic evidence (23%) (20).

The RPC model was developed to address systematic barriers and infrastructure needs that affect researchers’ engagement with policymakers to accelerate the implementation of evidence-based policy by using a 7-step process (21,22). Evaluation of this model shows a greater use of research evidence in legislative offices using this process and increased policy engagement among participating researchers (15,20). The RPC model comprises both capacity-building and collaboration components. More detailed descriptions of the RPC process can be found elsewhere (21), but an overview of the process is described below.

For capacity-building, Step 1 is assessing legislators’ policy goals and identifying policy champions on issues of interest. Once policy goals have been elucidated, researchers with relevant expertise are identified to form a resource network (Step 2). Step 3 involves matching policymakers with researchers who can provide relevant information or data to support legislative actions. Before engaging with legislators, researchers participate in training and ongoing technical assistance, providing context and skills to ensure effective communication between the legislator and the researchers (Step 4).

To build collaboration in policymaker–research matches, Step 5 of the RPC process entails rapid-response meetings, where legislative offices and researchers are brought together to discuss policy goals and develop a plan for relevant resource development and interactions. In Step 6, meetings are followed by initial strategic planning, which outlines goals, action steps, and timelines. Finally, Step 7 focuses on maintaining responsiveness to legislative interests and needs, which could include further involvement in the legislative process, such as testimony, research synthesis, or consultation. The success of this process depends on providing the infrastructure needed by researchers, most of whom are in academic institutions, to develop their knowledge transfer skills and provide needed resources for supporting the network and ongoing implementation (21).

Given the success of the RPC model in a federal context, a natural and useful extension of this work is to explore its applicability and potential impact on public health policy within state-level legislative processes. With its distinctive legislative session, Texas presents an ideal case for this exploration and offers a unique opportunity to assess the model’s adaptability and effectiveness in a regional legislative environment. This article details the process of adapting a national framework of researcher–policymaker collaboration to the state level and presents initial evaluation data on the awareness and application of evidence-based policy practices among Texas researchers and policymakers, as well as lessons learned.

The RPC model, designed for application at the federal level (20), was adapted for use within the Texas legislative process for the 2021 Legislative Session as the Texas Research-to-Policy Collaboration (TX RPC) Project ( Table 1 ). This adaptation of the federal RPC evaluation and project tools was informed by prior research conducted with Texas legislators (23) and with input from the developers of the federal RPC model. Recommendations from the members of the project’s advisory committee, which included academic partners and health policy experts, and university governmental relations advisors, further informed the adaptation process. Key modifications were made to ensure the TX RPC Project aligned with the unique timelines and procedures of the Texas legislative cycle. An emphasis was placed on child health legislation and research, reflecting the state’s specific needs, potential areas of bipartisan agreement (24), and the investigators’ area of expertise. Beyond adapting the RPC model, the TX RPC Project expanded its outreach to include newsletters, webinars, and “lunch and learn” sessions at the Capitol, complemented by a legislative bill tracker to monitor relevant policy developments.

The Texas legislature operates under a schedule mandated by the state constitution, convening every odd-numbered year (eg, 2021, 2023) for 140 days. This biennial session typically spans from the beginning of January through the end of May. Governance is provided by the Governor and Lieutenant Governor, elected by the voters, and the Speaker of the House, elected by the House of Representatives. Texas uses a bicameral legislative system, with 150 House members and 31 Senators. House representatives serve 2-year terms, while Senators serve 4-year terms, with elections staggered so that approximately half the Senate is elected every 2 years. Despite the short session, the legislature typically has 7,000 or more bills filed.

Adapting the RPC methodology to Texas maintained all 7 steps of the model but required logistical and procedural modifications ( Table 1 ). For example, the first 4 steps, which included assessing legislators’ goals, finding researchers with the appropriate expertise, matching legislators and researchers, and training researchers, were very similar to the federal RPC model. The short timeline of the Texas legislative session made it difficult to engage in many rapid-response meetings (Step 5) or to engage in significant strategic planning (Step 6), although we were able to maintain responsiveness to legislative needs (Step 7). Key format and procedural adaptations involved transitioning from federal to state-specific language and methods, which included updates in training protocols, use of shared sites for collaboration, and redesign of data request forms. Format and procedural adaptations included changes in language (federal to state) and methods (eg, training, shared sites, request forms). Modifying the RPC to fit the state legislature was complicated by the part-time availability of policymakers and their geographic dispersion across the state; thus, the RPC timeline was adjusted to accommodate a compressed, biennial legislative session. As a result, the evaluation design was altered to include a pre- and post-test survey and a different format for the researcher–legislator meetings, which included committees rather than one-on-one relationships. The unforeseen challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and the need for physical distancing also led to a pivot to virtual meetings, enabling continued collaboration between policymakers and the TX RPC Project researchers and team members.

Study population

Legislative offices.

Since this study sought to understand the use of public health research in the Texas legislature, the sample was purposively recruited to represent legislators who lead policy efforts in child and public health. Elected officials in the Texas Senate and House of Representatives previously involved in public health policy, expressing an interest in the topic, appointed to relevant legislative committees such as health and human services, or members of select caucuses were invited to join the TX RPC Project in November 2019. Project staff sent a maximum of 4 recruitment emails to 68 legislative offices, with the goal of enrolling 20 legislative offices. Interested offices received a telephone call follow-up from study staff. A reception event at the state capitol was also held to inform these and other legislators about the study. Interested policymakers and their staff were scheduled for an in-person baseline survey and semi-structured policy identification needs-assessment interview. Baseline assessments were conducted in January, February, and May 2020 with 21 policymakers or their staff, who provided verbal consent to participate.

Researchers

Experts in health research from academic, nonacademic, and nonprofit settings in Texas were invited to join the TX RPC Project network of researchers in November 2019 based on their expertise and location in Texas. Project staff contacted 111 researchers by individual email but also recruited researchers through academic or state coalition listservs and an internal weekly newsletter. Up to 3 follow-up emails and phone calls were sent to interested researchers to enroll at least 50 researchers in the network. Researchers interested in participating completed the informed consent form, intake form, and baseline survey online using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) software (25). Training to build capacity for engaging with legislators was offered in person and online to participating researchers, with a goal of training 20 to 30 researchers.

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas School of Public Health Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (no. HSC-SPH-19–0539) reviewed the study and determined it to be exempt for both researchers and legislators.

Collaborative partnerships

Researchers in the TX RPC Project Network were matched with participating legislative offices to meet to develop ongoing relationships and provide public health data and resources in preparation for the 2021 Texas Legislative Session. Researchers were matched to legislators based on 1) alignment with legislators’ district location, 2) expertise in reported public health policy priorities of the legislator, 3) availability to commit to a partnership, and 4) high level of engagement in the TX RPC Project Network. The project goal was to support 10 researcher–policymaker partnerships. Forty-five researchers were matched with 21 legislative offices to form collaborative partnerships. Additional researchers who were interested in the project but did not have the time for a legislator match were designated as “resource” members. These researchers served in an ad hoc role, providing expertise when needed for specific legislative requests or other activities (eg, webinars).

The baseline survey for legislators or their aides was drawn from previous work that established the structural validity of scales used in this study (26). These surveys were conducted in person and assessed 1) use of research evidence (5 items); 2) perceived value of research evidence for policy work (6 items); 3) past and current interactions with researchers (8 items); 4) information sources (19 items); and 5) research training of office staff (4 items). For closed-ended questions, policymakers or their staff indicated agreement using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 5 = all the time, or 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). Scales were developed for each construct by summing responses to the individual items.

The semi-structured policy identification needs assessment interview included semi-structured, open-ended questions to ask legislators or their designated staff about 1) policy priorities related to health, well-being, or wellness promotion, 2) strategies to strengthen the impact of policies, and 3) engaging researchers to support health policy efforts. Data from these interviews were used to help our research team prioritize health policy topics for briefs, webinars, and legislative bill tracking, as well as give us insight into each individual legislator’s need for information so that we could match legislators with researchers who had expertise in each health policy area.

The online researcher intake form to determine study eligibility collected self-reported demographic information (ie, contact information and organization affiliation), areas of research expertise, prior policy experiences, available time commitment, and preferences for online versus in-person training.

The researchers’ baseline survey was drawn from previous work that piloted these measures in the RPC pilot in Congress (7). The TX RPC Project surveys were conducted in an online format and assessed 1) prior policy experiences (1 item); 2) recent policy engagement (14 items); 3) policy-informed research activities (4 items); 4) perceived self-efficacy for engaging with public officials (10 items); 5) reported policy knowledge (7 items); and 6) training needs (9 items). For these closed-ended questions, response options varied; for questions asking about recent policy engagement, researchers responded on a 4-point categorical scale (1 = none to 4 = ≥7 times); for questions about policy-informed research activities, reported policy knowledge, and training needs, researchers responded on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree); and for questions regarding perceived self-efficacy engaging with public officials, researchers responded on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true to 4 = exactly true). Scales were developed for all constructs except prior policy experience by summing responses to individual items.

Data analysis

All analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel 2007/2016 for Windows XP and Stata software version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC). Descriptive statistics (including frequencies and percentages) were calculated for each question in the baseline assessments and for demographic information. For each set of questions, means, standard deviations, and Cronbach α were calculated for the scaled sum of items. Person mean imputation was performed for missing data, where at least 1 item in the scale was nonmissing, to minimize bias introduced by simple case deletion (27). For the researcher training evaluation, mean and standard deviation were calculated for each question and scale. Policy priorities were categorized by health topic at baseline. Semi-structured interview notes were entered into a database, and three research team members performed content analysis to identify relevant themes using standard inductive qualitative methods (28,29).

Legislators (n = 21) included both senators and representatives, with a majority (57.1%) from the Texas House of Representatives; most were female (61.9%). Almost all (90.5%) legislators participated in re-election campaigns in November 2020. Eighty-three researchers enrolled in the TX RPC Project Network, and 59 completed the policy capacity training. Researchers were predominantly female (66.3%) and academics with a university affiliation (89.1%).

Interviews were conducted with legislators and their staff, including legislative directors, chiefs of staff, legislative assistants and aides, policy analysts, an education specialist, and a district director. The most frequently mentioned health policy priority ( Table 2 ) was health care access/Medicare/Medicaid, which 76.2% of legislators identified as a significant area of concern. Health policy topics mentioned by 40% or more of the respondents included mental health, health disparities, vaping/e-cigarettes, and maternal and child health. Other health policy priorities were Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)/food insecurity, school nutrition, immunizations, disabilities, and violence prevention ( Table 2 ). Because most legislative interviews were conducted in early 2020, COVID-19–related health policy was rarely mentioned.

Baseline surveys were collected from 73 researchers and 21 legislators ( Table 3 ). Most researchers indicated little prior engagement with policymakers, especially during the policy creation process. In general, researchers tended to agree that policy informed their work but also reported moderate levels of policy-related self-efficacy and policy knowledge. Most researchers reported that they needed more training regarding policy-related training needs ( Table 3 ).

Legislative offices generally reported a high use of research in policy development, and many strongly agreed that it was valuable to use research in their work. Despite these views, legislative offices reported few interactions with researchers, especially working with researchers to identify research direction or priorities (eg, informing researcher work). Legislative offices often obtained policy-related information from people involved with the policy or program, Texas data, and nonprofit organizations or foundations; however, fewer legislative offices reported obtaining information from researchers, conferences, or program-specific materials ( Table 3 ).

Adaptation of the RPC to a state-level government is feasible but must include changes in logistics that depend on the unique structures and practices of the state legislative body. Health policy priorities identified at the state level by legislative offices included mental health, vaping/e-cigarette use, health disparities, health care access, and food insecurity, all important public health issues. Baseline survey data showed that researchers do not frequently engage with legislative offices in a structured manner across the policy development spectrum and that researchers require training in these skills. Legislative officials realize the value of research, especially state-level data, but do not often engage with researchers. Thus, there is a need for a coordinating organization and process to develop and maintain trusted relationships between researchers and legislative offices.

The adaptation of the RPC process to Texas posed unique issues. For example, Texas is 1 of only 4 states with a legislature that meets on a biennial basis (30). This compressed schedule leads to policy development before the actual session and often before the election. Most Texas legislators tend to reside in the state capitol for the 140-day term and then return to their districts and a primary job. In terms of establishing partnerships between policymakers and researchers, this schedule leads to fewer opportunities to interact with policymakers, the necessity of interacting with policymakers in their home districts rather than in the Capitol, and limited time to develop new legislation. The short session also required proactive steps to develop a library of potential resource materials ahead of actual requests based on input from the project advisory committee.

Conducting this work during a pandemic also presented several challenges but additional opportunities. Originally, in-person meetings between researchers and legislators were proposed, which would have necessitated travel expenses for researchers across the state. Since the COVID-19 pandemic led to social distancing, many offices were not at the Capitol during the interim period (2020), and researcher–legislative office meetings were pivoted to an online secure video forum using WebEx. Although the project was not able to arrange face-to-face meetings, the video format provided project cost savings and easier scheduling. The pandemic also resulted in several requests for COVID-19 and vaccine-related data and information, which became a major focus of the TX RPC Project.

As with other studies (15,20), our work indicated that researchers generally do not actively engage with policymakers and need additional training, especially in facilitating communication and building trusted relationships with legislators (6,9,31). The RPC project provided training, update meetings, communications, support from the research staff, and resources for both researchers and legislators. This support is necessary, as policy-related activities, which fall under knowledge translation or community-engaged research, often do not count toward the tenure and promotion metrics valued in traditional academic environments (9,21,32). Recent work has called for better inclusion of these activities as academic metrics, in addition to bibliographic output and funding, but universities have not widely adopted this practice (32,33).

Although legislative offices reported using research in health policy development, few reported connecting directly with academics and researchers. Consistent with prior research, potential reasons for limited contact between legislative offices and researchers include inadequate translation of complex research into practical recommendations (34), infrequent interactions between policymakers and legislative offices, and differences in culture (10,11). Training is necessary to overcome some of these communication barriers (31). Building trusted relationships between researchers and legislators facilitates advancing evidence-based policy, providing further evidence for the TX RPC Project approach (12). A recent adaptation of the RPC model, the SciComm Optimizer for Policy Engagement (SCOPE), connected researchers and state legislators using email and was evaluated by using a randomized controlled trial. Results showed that legislators who received the intervention were more likely to use research evidence in their social media posts (35). The TX RPC Project model included more engagement and outreach than the SCOPE process, which might be necessary for a short legislative session like that in Texas. Thus, models for connecting researchers and state legislators can accelerate the knowledge transfer of research into public health action, but further evaluation methods should be used to determine effectiveness.

The TX RPC Project model sought to accelerate the adoption and reach of evidence-based public health policy (36) at the state level. The TX RPC Project was the first adaptation of the federal RPC process in which the model developers did not oversee its implementation. Thus, the TX RPC Project provides evidence of scalability and institutionalization of the RPC process in a different setting, suggesting that implementation science approaches can be applied to health policy work (36).

Although the TX RPC Project has several strengths, including building on an existing evidence-based model, current governmental and legislative relationships, and evaluation of the process, there are several limitations. Twenty-one legislators participated in the project, so their views may not reflect the dominant views in the Texas legislature. Alternatively, these legislators might represent the subset interested in advancing public health policy. The participating legislators were identified for their interest in health policy but not for their views on other policy domains. Ideally, every legislator in the Texas legislature would be recruited, but given the short session and limited resources, we chose to prioritize those legislators who were most likely to file and advance health policy legislation. The Texas RPC newsletters were sent to all Texas legislators, and a request form was included that invited legislative offices to contact us for any information related to health policy. Additionally, many of the outcomes of this study are largely based on self-reported process-oriented data. Still, this study demonstrates the utility of the RPC model in a state environment and provides an in-depth evaluation of how Texas legislators view public health researchers as experts in developing effective health policy at the state level.

The TX RPC Project illustrates some of the benefits and challenges of linking researchers to policymakers using a model that has been successful at the federal level. With the past few years of federal Congressional gridlock, state legislators are a promising means of innovating health policy (37). Thus, further work at enhancing strategies that promote evidence-based health policy that addresses the political determinants of health (4) at the state level can lead to improved health outcomes that can, in turn, be used as exemplars for other states and the nation.

The authors do not have any conflict of interest to report or relationships that might lead to bias or a conflict of interest. No copyrighted material, surveys, instruments, or tools were used in the research described in this article. This project was funded by the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation. The co-authors acknowledge the contributions of the TX RPC Project Advisory Committee members and the government relations staff of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Yuzi Zhang, PhD, and Melissa Campos-Hernandez, MPH, for formatting assistance.

D.M.H. obtained study funding, developed the study design and evaluation, oversaw data collection, and drafted and edited the manuscript; A.vdB. assisted in the development of the study design and evaluation, including evaluation instruments, and edited the manuscript; A.E.R. assisted in the development of study materials and evaluation instruments, collected, and analyzed study data, and edited the manuscript; S.F.T. conducted data collection and management, and drafted and edited the manuscript. T.M. provided project management for the study, oversaw recruitment and data collection, provided input on evaluation measures, and drafted and edited the manuscript; K.M., C.J. conducted participant recruitment, supported the researcher training sessions, provided input on evaluation measures, and edited the manuscript; A.H. assisted in the development of the study design and edited the manuscript; J.T.M. served on the Advisory Committee and edited the manuscript; E.L. contributed to the survey design; D.M.C. advised the study design; J.T.S. contributed to all aspects of the evaluation methodology and advised the model adaptation, and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding Author: Deanna M. Hoelscher, PhD, RD, LD, CNS, Michael & Susan Dell Center for Healthy Living, 1836 San Jacinto Blvd, Ste 571, Austin, TX 78701 ( [email protected] ).

Author Affiliations: 1 Michael & Susan Dell Center for Healthy Living, Austin, Texas. 2 The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth Houston) School of Public Health, Austin, Texas. 3 University of Illinois Cancer Center, Chicago, Illinois. 4 Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, West Lake Hills, Texas. 5 Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia. 6 Edna Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania.

- Adler NE, Glymour MM, Fielding J. Addressing social determinants of health and health inequalities. JAMA . 2016;316(16):1641–1642. PubMed doi:10.1001/jama.2016.14058

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health at CDC. Updated December 8, 2022. Accessed August 16, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/about/priorities/social-determinants-of-health-at-cdc.html

- Marmot M. Closing the health gap. Scand J Public Health . 2017;45(7):723–731. PubMed doi:10.1177/1403494817717433

- Dawes DE. The political determinants of health. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins Press; 2020.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy people 2030: SDOH-07. Increase the proportion of the voting-age citizens who vote. Accessed August 16, 2024. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives/social-and-community-context/increase-proportion-voting-age-citizens-who-vote-sdoh-07

- Brownson RC, Royer C, Ewing R, McBride TD. Researchers and policymakers: travelers in parallel universes. Am J Prev Med . 2006;30(2):164–172. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.004

- Scott JT, Larson JC, Buckingham SL, Maton KI, Crowley DM. Bridging the research–policy divide: pathways to engagement and skill development. Am J Orthopsychiatry . 2019;89(4):434–441. PubMed doi:10.1037/ort0000389

- Brennan LK, Brownson RC, Orleans CT. Childhood obesity policy research and practice: evidence for policy and environmental strategies. Am J Prev Med . 2014;46(1):e1–e16. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.08.022

- Otten JJ, Dodson EA, Fleischhacker S, Siddiqi S, Quinn EL. Getting research to the policy table: a qualitative study with public health researchers on engaging with policy makers. Prev Chronic Dis . 2015;12:E56. PubMed doi:10.5888/pcd12.140546

- Innvaer S, Vist G, Trommald M, Oxman A. Health policy-makers’ perceptions of their use of evidence: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy . 2002;7(4):239–244. PubMed doi:10.1258/135581902320432778

- Orton L, Lloyd-Williams F, Taylor-Robinson D, O’Flaherty M, Capewell S. The use of research evidence in public health decision making processes: systematic review. PLoS One . 2011;6(7):e21704. PubMed doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021704

- Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T, Woodman J, Thomas J. A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res . 2014;14(1):2. PubMed doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-2

- Caplan N. The two-communities theory and knowledge utilization. Am Behav Sci . 1979;22(3):459–470.

- Tseng V. The uses of research in policy and practice and commentaries. Soc Policy Rep . 2012;26(2):1–24.

- Crowley DM, Scott JT, Long EC, Green L, Israel A, Supplee L, et al. . Lawmakers’ use of scientific evidence can be improved. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2021;118(9):e2012955118. PubMed doi:10.1073/pnas.2012955118

- Haynes AS, Derrick GE, Redman S, Hall WD, Gillespie JA, Chapman S, et al. . Identifying trustworthy experts: how do policymakers find and assess public health researchers worth consulting or collaborating with? PLoS One . 2012;7(3):e32665. PubMed doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032665

- Oliver K, Cairney P. The do’s and don’ts of influencing policy: a systematic review of advice to academics. Palgrave Commun . 2019;5(1):1–11.

- Wehrens R. Beyond two communities — from research utilization and knowledge translation to co-production? Public Health . 2014;128(6):545–551. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2014.02.004

- Oliver K, Boaz A. Transforming evidence for policy and practice: creating space for new conversations. Palgrave Commun . 2019;5(1):60.

- Crowley M, Scott JTB, Fishbein D. Translating prevention research for evidence-based policymaking: results from the Research-to-Policy Collaboration pilot. Prev Sci . 2018;19(2):260–270.

- Scott T, Crowley M, Long E, Balma B, Pugel J, Gay B, et al. . Shifting the paradigm of research-to-policy impact: Infrastructure for improving researcher engagement and collective action. Dev Psychopathol . 2024;22:1–14. PubMed doi:10.1017/S0954579424000270

- TrestleLink. Research-to-policy collaboration. Accessed August 16, 2024. https://trestlelink.org/models/research-to-policy-collaboration/

- Nichols D, Dowdy D, Atteberry H, Menendez T, Hoelscher D. Texas Legislator Survey: lessons learned from interviewing state politicians about obesity policies. Texas Public Health J. 2017;69(2):14–23.

- Bogenschneider K, Day E, Bogenschneider BN. A window into youth and family policy: state policymaker views on polarization and research utilization. Am Psychol . 2021;76(7):1143–1158. PubMed doi:10.1037/amp0000681

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) — a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform . 2009;42(2):377–381. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Long EC, Smith RL, Scott JT, Gay B, Giray C, Storace R, et al. . A new measure to understand the role of science in US Congress: lessons learned from the Legislative Use of Research Survey (LURS). Evid Policy . 2021;17(4):689–707. PubMed doi:10.1332/174426421X16134931606126

- Downey RG, King C. Missing data in Likert ratings: a comparison of replacement methods. J Gen Psychol . 1998;125(2):175–191. PubMed doi:10.1080/00221309809595542

- Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2014.

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs . 2008;62(1):107–115. PubMed doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Ballotpedia. Dates of 2024 state legislative sessions. Accessed September 30, 2024. https://ballotpedia.org/Dates_of_2024_state_legislative_sessions

- Brandert K, McCarthy C, Grimm B, Svoboda C, Palm D, Stimpson JP. A model for training public health workers in health policy: the Nebraska Health Policy Academy. Prev Chronic Dis . 2014;11:E82. PubMed doi:10.5888/pcd11.140108

- Sibley KM, Khan M, Banner D, Driedger SM, Gainforth HL, Graham ID, et al. . Recognition of knowledge translation practice in Canadian health sciences tenure and promotion: a content analysis of institutional policy documents. PLoS One . 2022;17(11):e0276586. PubMed doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0276586

- Alperin JP, Muñoz Nieves C, Schimanski LA, Fischman GE, Niles MT, McKiernan EC. How significant are the public dimensions of faculty work in review, promotion and tenure documents? eLife . 2019;8(8):e42254. PubMed doi:10.7554/eLife.42254

- Stamatakis KA, McBride TD, Brownson RC. Communicating prevention messages to policy makers: the role of stories in promoting physical activity. J Phys Act Health . 2010;7(suppl 1):S99–S107. PubMed doi:10.1123/jpah.7.s1.s99

- Scott JT, Collier KM, Pugel J, O’Neill P, Long EC, Fernandes MA, et al. . SciComm Optimizer for Policy Engagement: a randomized controlled trial of the SCOPE model on state legislators’ research use in public discourse. Implement Sci . 2023;18(1):12. PubMed doi:10.1186/s13012-023-01268-1

- Purtle J, Moucheraud C, Yang LH, Shelley D. Four very basic ways to think about policy in implementation science. Implement Sci Commun . 2023;4(1):111.

- Sallis JF, Story M, Lou D. Study designs and analytic strategies for environmental and policy research on obesity, physical activity, and diet: recommendations from a meeting of experts. Am J Prev Med . 2009;36(2):S72–S77. PubMed doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.10.006

Abbreviation: SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Abbreviations: TX RPC, Texas Research-to-Policy Collaboration; SD, standard deviation. a Missing, researchers: proactively contacted policymakers to talk about research related to policy issues, n = 72; setting their agenda, n = 72; evaluating a policy or program’s effectiveness or impact, n = 72; deciding about the content or direction of a policy or program, n = 72; I can discuss solving difficult problems, n = 70; if staff oppose me, I can find means to negotiate our different viewpoints, n = 69; it is easy for me to stick to my aims and accomplish my goals, n = 67; I am confident that I could deal efficiently with unexpected issues that come up, n = 69; I am resourceful during meetings, which allows me to handle unforeseen situations, n = 68; I can discuss most problems without eliciting conflict if I invest the necessary effort, n = 68; I can remain calm when facing difficulties because I can rely on my coping abilities, n = 69; when staff confront me with a problem, I can usually find several solutions, n = 68; if I encounter conflict during discussion, I can usually think of a solution, n = 68; I can usually handle whatever comes my way during conversations, n = 67; the multiple factors that policymakers must consider when making decisions, n = 72; the primary information sources policymakers use for decision-making, n = 72; how policymakers’ timeframe for action differs from researchers, n = 72; the ways in which policymakers define evidence, n = 72; common perceptions of researchers that hinder developing trusting relationships with policymakers, n = 72; how to make contact with legislative offices, n = 71; ways I can seek to support legislative offices, n = 70; communicating with policymakers and staff, n = 70; understanding the legislative process and where researchers can play a role, n = 71; how to work with legislative offices, n = 70; best practices for synthesizing literature, n = 72; responding to needs of legislative offices, n = 70; regulations on lobbying and advocacy, n = 71; maintaining a working relationship with legislative offices, n = 70; engaging with advocacy groups, n = 69; responding or engaging with media, n = 71). b Missing, legislators: persuade others to a point of view or course of action, n = 20; attending forums (eg, conference, briefing, webinar) to hear about research findings, n = 20; collaborating with researchers to interpret research findings, n = 20; calling upon researchers to testify at a hearing, n = 20).

The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors’ affiliated institutions.

- Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

- Biostatistics

- Environmental Health and Engineering

- Epidemiology

Health Policy and Management

- Health, Behavior and Society

- International Health

- Mental Health

- Molecular Microbiology and Immunology

- Population, Family and Reproductive Health

- Program Finder

- Admissions Services

- Course Directory

- Academic Calendar

- Hybrid Campus

- Lecture Series

- Convocation

- Strategy and Development

- Implementation and Impact

- Integrity and Oversight

- In the School

- In the Field

- In Baltimore

- Resources for Practitioners

- Articles & News Releases

- In The News

- Statements & Announcements

- At a Glance

- Student Life

- Strategic Priorities

- Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, and Equity (IDARE)

- What is Public Health?

We advance evidence-informed solutions to systemic public health challenges and train tomorrow’s leading health administrators, advocates, policymakers, and researchers.

Explore our Programs

- Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, Equity in Health Policy and Management

- Job Openings

- HPM Postdoctoral Training

- New Policy Proposal Seeks to Improve Access to Medications that Prevent HIV Infection

- HPM PhD Students

- HPM Students

- Job Seeking PhD Candidates

- Distinguished Policy Scholar

- News and Events

- Make a Gift

Health Policy & Management Headlines

Guns remain leading cause of death for children and teens.

Center for Gun Violence Solutions latest annual report highlights CDC 2022 firearm deaths, with focus on young people and people of color

New Study Shows Bipartisan Struggles with Depression, Reveals Gaps in Mental Health Care Access

A new study published in September in the Journal of Public Health Management and Practice sheds light on the mental health crisis gripping millions of Americans, and the findings suggest that depression is a bipartisan issue that affects people across party lines.

Student Spotlight: Glendedora Dolce

For graduate students who are passionate about putting research and policy recommendations into action, the Johns Hopkins Health Policy Institute (HPI) is an invaluable experience. Among the Spring 2024 HPI Fellows is Glendedora Dolce, now in her second year as a Health and Public Policy doctoral student. Glendora's research aims to prevent injuries, illnesses, and health disparities as it pertains to child passenger safety.

What We Do in the Department of Health Policy and Management

Our faculty, staff and students are committed to solving the most entrenched public health challenges in the world through evidence-based policy change.

2023 - 2024 Year in Review

Every day, the Department of Health Policy & Management advances evidence-informed solutions to public health challenges and trains the next generation of leading health administrators, advocates, policymakers and researchers. Learn more about HPM's impact in the 2023 - 2024 academic year.

Health Policy and Management Highlights

Health Policy & Management Department in the 2024 - 2025 U.S. News & World Report

students and 2,000+ alumni

full-time faculty

research centers

Health Policy and Management Programs

As one of the largest health policy and management programs in the country, we are dedicated to advancing local, national, and global health policy to make a difference.

Within four degree programs (three master’s and the PhD), students have opportunities to engage directly with faculty, study internationally, and complete practicums in the field, contributing directly to global policy.

Our students graduate with marketable skills and real-world experience, ready to make an impact, from the #1 school of public health.

Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Health Policy and Management

Our PhD program trains students to conduct original investigator-initiated research through a combination of coursework and research mentoring.

Master of Science in Public Health (MSPH) in Health Policy

MSPH students evaluate health care and work with decision makers to identify relevant regulatory policies, strategies, and interventions. This program also prepares students for further doctoral training in economics and health policy.

Master of Health Administration (MHA)

The Master of Health Administration (MHA) program is uniquely designed for future health care executives early in their careers. The two-year accelerated curriculum includes one year of full-time academic coursework followed by a full-time, 11-month compensated administrative residency in one of many Hopkins affiliates and partner institutions across the country.

Master of Health Science (MHS) in Health Economics and Outcomes Research

The MHS in Health Economics and Outcomes Research is a professionally-oriented degree program designed for individuals seeking specialized academic training to establish or expand their careers as health policy analysts.

Meet the Chair of Health Policy and Management

Keshia M. Pollack Porter, PhD, MPH, an expert in advancing health equity and policy change that promotes safe and healthy environments, has been named chair of the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Her vision for the Department includes amplifying research, dissemination, and training activities with a particular focus on health equity.

Centers and Institutes in the Department of Health Policy and Management

We are home to 18 research and practice-based centers and institutes that focus on a range of public health issues. We also co-direct the Johns Hopkins-Pompeu Fabra University Public Policy Center, a collaboration between Johns Hopkins University, the Bloomberg School and the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, Spain.

Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions

Johns hopkins center for health disparities solutions, center for health services and outcomes research (chsor), johns hopkins center for injury research and policy, center for law and the public's health, center for mental health and addiction policy, center for population health information technology (cphit), johns hopkins evidence-based practice center, institute for health and social policy (ihsp), johns hopkins primary care policy center, the risk sciences and public policy institute at the bloomberg school, the roger and flo lipitz center to advance policy in aging and disability, johns hopkins berman institute of bioethics, hopkins’ economics of alzheimer’s disease & services center, lerner center for public health advocacy, hopkins business of health initiative, about the department's commitment to idare.

The Department of Health Policy and Management is committed to building an inclusive environment where faculty, staff, students, and other members of our community support efforts to dismantle structural oppression and racist policies and practices. The work of faculty, staff, and students in the department often focuses on the intersection of racism, health disparities and inequities, and policies that are on the forefront of national discussions. We are strengthened by our diverse community and understand the critical need for differences and perspectives and understand we have work to do to bring our own department in alignment with the goals of IDARE. Our goal is for all students, faculty, and staff in the department to be adequately equipped to advocate for policies and practices that advance diversity, equity, and inclusion activities within our own department.

Kadija Ferryman, PhD

is a trailblazing anthropologist who examines how race, policy and ethics interact with health technology.

Meet Our Job-Seeking PhD Candidates

Our PhD candidates are seeking solutions to major health policy challenges. Read about their work and where they are headed with their careers.

Support Our Department

A gift to our department can help to provide student scholarships and internships, attract and retain faculty, and support innovation.

Follow Our Department

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

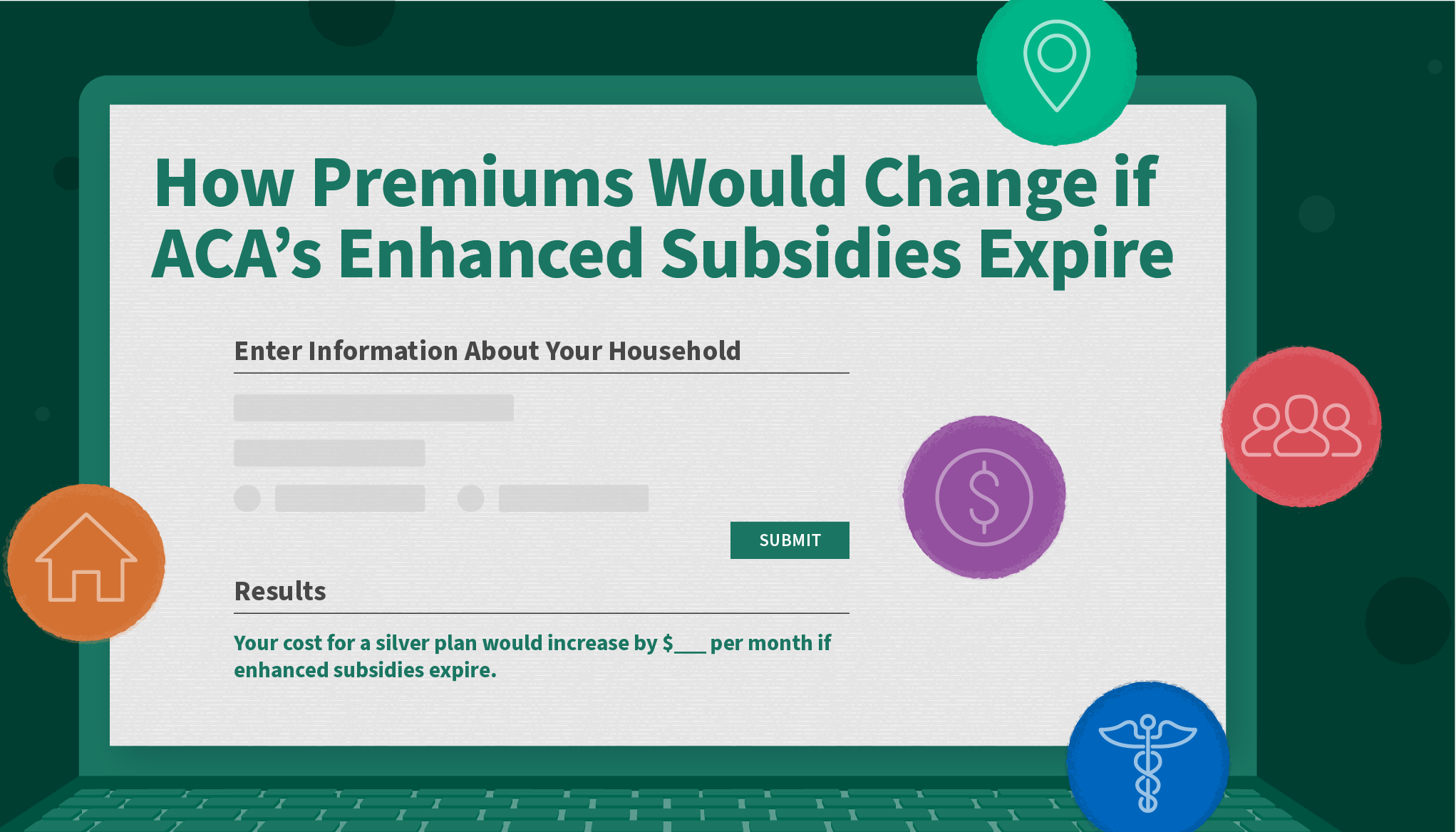

How Much More Would People Pay if Enhanced ACA Subsidies Expired?

What Happens if Enhanced Subsidies Expire?

Where aca enrollment is growing the fastest, 2025 marketplace enrollment tools, quick takes.

Nov 18, 2024

Fewer than a quarter of voters want to decrease government involvement in ensuring childhood vaccinations, suggesting the public may not be eager for disruption in this area. … more

Robin Rudowitz

Nov 14, 2024

While Medicaid did not receive a lot of attention during the campaign, if cuts to Social Security and Medicare are largely off the table, Medicaid is the likely source of funding to extend expiring tax cuts. … more

How Can Key Federal Health Agencies Affect Vaccine Policies?

Childhood Vaccination Rates Continue to Decline

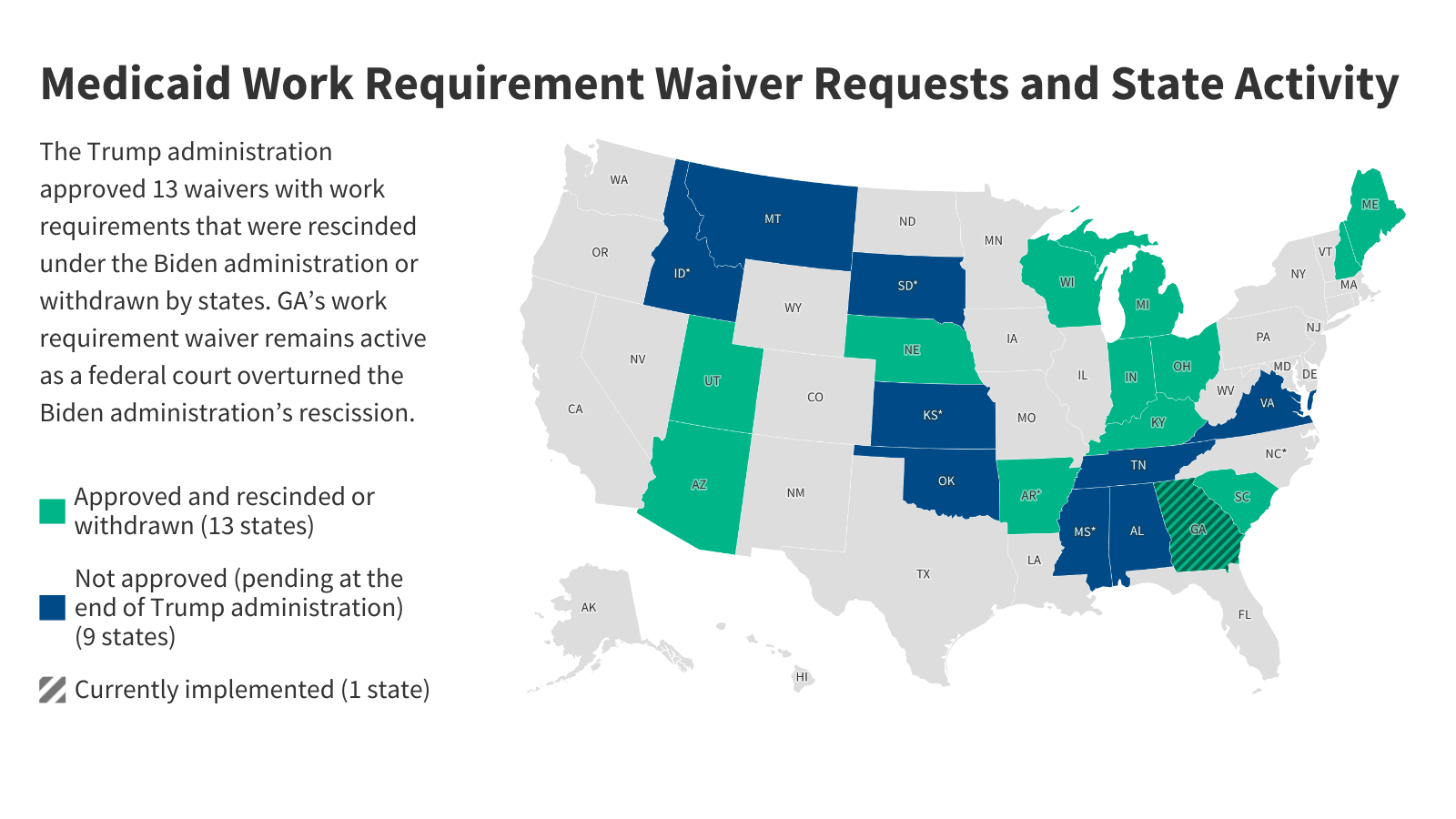

The public’s views on vaccines, mandates and more, state health facts data collection: vaccinations, medicaid work requirements may return to the agenda in the next trump administration.

What Administrative Changes Can a Trump Administration Make to Medicaid?

How medicaid financing works and what that means for proposals to change it, fact sheets: who does medicaid cover in your state, kff health news logo latest news.

Georgians With Disabilities Are Still Being Institutionalized, Despite Federal Oversight

TV’s Dr. Oz Invested in Businesses Regulated by Agency Trump Wants Him To Lead

KFF Health News' 'What the Health?': Trump’s Nontraditional Health Picks

Florida Gov. DeSantis’ Canadian Drug Import Plan Goes Nowhere After FDA Approval

A first look at medicare advantage plans offered in 2025.

The average Medicare beneficiary can choose among plans offered by eight firms in 2025. Three new insurers entered the Medicare Advantage market in 2025, while eight firms exited the market in 2025.

Distrust in Food Safety and Social Media Content Moderation

The latest Health Misinformation Monitor addresses rising distrust in food safety, shifts in social media content moderation, and the trend of self-diagnosis and treatment based on social media videos.

Immigration Policies and Health Under a Trump Administration

Key changes to immigration policies that may take place under the second Trump administration based on his previous record and campaign statements, and their implications for health and the economy.

Beyond the Data, a Column by Drew Altman

In his regular Beyond the Data columns, CEO Drew Altman discusses what the data, polls, and journalism produced by KFF mean for policy and for people.

Browse the Latest from KFF

COMMENTS

Overview. Health policy and systems research (HPSR) is an emerging field that seeks to understand and improve how societies organize themselves in achieving collective health goals, and how different actors interact in the policy and implementation processes to contribute to policy outcomes. By nature, it is inter-disciplinary, a blend of ...

Health Affairs, the leading journal of health policy research, offers a nonpartisan forum to promote analysis and discussions on improving health. With our podcasts, we go beyond the papers to ...

Health Research Policy and Systems (2018) 16:4. The authors aim to identify the top priority issues that impede the conduct, reporting and use of economic evaluation as well as potential solutions as an input for future research topics by the international Decision Support Initiative and other movements.

Topics in Health Affairs journal, Forefront, briefs and other content cover a wide swath of health policy matters and health services research. Fields range from economics to political science to ...

The PhD in Health Services Research and Health Policy at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University is a full-time program that trains researchers in the fields of health policy, health economics, health management, and health services research. Students take doctoral-level classes in the Department of Economics, the Department of ...

New Study Highlights Link Between Minimum Wage, Income Inequality, and Obesity Rates Across U.S. Counties. November 11, 2024. A new study published in the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities in October reveals a significant interaction between minimum wage policy, income inequality , and obesity rates in U.S. counties.

Policy Atlas is a free, web-based, curated research platform that catalogues downloadable policy-relevant data, use cases, and instructional materials and tools to facilitate health policy research. The Policy Atlas includes data on various health topics and policies, and may be used for research, evaluation, or a quick summary of state ...