An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Working from home during the COVID‐19 pandemic, its effects on health, and recommendations: The pandemic and beyond

Canan birimoglu okuyan , phd, mehmet a begen , phd.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence Mehmet A. Begen, PhD, Ivey Business School, Western University, Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Western University, 1255 Western Road, London N6G 0N1, Ontario, Canada. Email: [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Received 2020 Dec 25; Accepted 2021 Apr 27; Issue date 2022 Jan.

This article is being made freely available through PubMed Central as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency response. It can be used for unrestricted research re-use and analysis in any form or by any means with acknowledgement of the original source, for the duration of the public health emergency.

We provide an overview of how to work from home during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic and what measures should be taken to minimize the negative effects of working from during this time.

Conclusions

The COVID‐19 pandemic has forced an adaptation process for the whole world and working life. One of the most adaptation measures is working from home. Working from home comes with challenges and concerns but it also has favorable aspects.

Practice Implications

It is crucial to develop and implement best practices for working from home to maintain a good level of productivity, achieve the right level of work and life balance and maintain a good level of physical and mental health.

Keywords: COVID‐19, mental health, physical health, working from home

A discussion of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) effects on our daily and work lives;

An overview of working from home, especially during the COVID‐19 pandemic;

Recommendations for working from home during COVID‐19.

1. INTRODUCTION

Until the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic is under control (and its subsequent waves are over), millions of people from all over the world have entered into an adaptation process and are following physical distancing requirements, stay home calls and lockdown orders to minimize contact with others, reduce the spread of the disease and flatten the curve. 1 Lockdown orders or stay home calls cover at least one‐third of the global population 2 and it has been the case for most Americans. 3 The COVID‐19 pandemic in general and especially these lockdowns, stay home calls and physical distancing have had a significant impact on our daily lives, from work to traveling, from schools to social life and more. Furthermore, the pandemic has affected the physical and mental health of many people. The results of a recent study done during the pandemic revealed that 37% of individuals experienced posttraumatic stress, 20.8% experienced anxiety, 17.3% had depression symptoms, 7.3% had sleep problems, 21.8% experienced a high level of perceived stress, and 22.9% had adjustment disorder, and one of the biggest challenges of the pandemic adaptation process has been the switch to working from home. 4

Working from home has been one of the most important and visible changes during the pandemic, it has gained even more significance, and more people have started (or had to start) working from due to lock‐downs orders and stay home calls. Even before the pandemic, working from home was getting traction. 5 For example, some JetBlue employees had been working from home since early 2000s. 6 In a research conducted in the United States 7 and several European countries, it was stated that 40% of all work activities could be done from home. 8 , 9 Another study revealed that the annual rate of working from home in the United States increased to 37% in 2015 while it was 9% in 1995. 10 Also, 7% of employees in the United States have an allowance for “flexible workplace” or telecommuting access. However, these employees are mostly managers, white‐collar staff, and high‐paid professionals. 11 In Europe, 5.2% of people aged 15–64 regularly worked from home in 2018, and this rate was higher in some of the countries, for example, 14% in the Netherlands, 13.3% in Finland, 11% in Luxembourg, 10% in Austria. 12 , 13

The pandemic has caused 46% of the businesses in the United States to implement telecommuting policies as of February 2020. 14 In another example, Canadian Bank of Montreal has announced that 80% of its employees can and will most likely continue working from home even after the pandemic. 15 Some occupational groups can easily adapt to working from home, whereas it is a much more difficult experience for others. For example, while academics and interpreters adapt more easily to working from home, other groups, such as teachers, have had difficulty working from home. This could be partly explained by the nature of occupation (e.g., individual vs. need to work with others in real‐time), previous experiences, the suitability of home for work (e.g., physical space availability, caregiver responsibilities, Internet connection accessibility) and other reasons. 16 , 17 A recent study shows that the rate of working from home is lower in developing countries (22%) compared to developed ones (37%). 18 This suggests that financial conditions and challenges of work environment can be two critical interrelated factors. While one always tries to adapt their lifestyles to their work, it is not possible to do this most of the time. Although mobile and Internet‐based technologies are gradually diminishing the importance of physical work requirements, conditions and facilities of the work environments are still critical. As long as home can provide a suitable and feasible working environment, many people may choose working from home option if or when available. And as mentioned above working from home was already getting popular before the pandemic and now with the pandemic it has become even more popular and sometimes necessary in most of the world, in developed and developing countries. Before the pandemic, some jobs' delivery was never considered to be possible or feasible as an online or remote option, such as doctor appointments via phone/Internet in Canada. However, now it seems telehealth is the new normal for Canada and many other countries and it is here to stay even after the pandemic.

Like anything else, working from home is a tradeoff and it has disadvantages as well as advantages. 19

The positive aspects of working from home include freedom of work schedule, 20 more time for and with family and increased leisure time, 21 lower stress and improved efficiency, 22 and cost and time savings on commuting to work. 20 Besides all the benefits and advantages of working from home, there are adverse factors that can lead to loss of control and reduced productivity while working from home. 23 Such factors are managing work and family obligations in the same environment and at the same time, 24 having a nervous and tense mood due to prolonged stay at home while working, spending too much time at home, risk of obesity (due to easy access and excessive eating/drinking), lack of working transparency, difficulty in accessing relevant technology and important documents from home securely, difficulty in controlling the balance between work and life, difficulty in communication and coordination, social isolation, and disruption of children's educational processes due to schools and nurseries' being closed during the pandemic. 25 , 26

Minimizing the negative effects of working from home and generating solutions to decrease adverse factors associated with the disadvantages of working from home are critical for maintaining the productivity and well‐being of individuals at all times but especially during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Adverse effects of the COVID‐19 pandemic has been an active area of research in countries such as Italy and Spain, where the effects of the pandemic have been severe, and in China where the disease first appeared. 4 , 27 , 28 In this article, we aim to provide an overview of how to work from home during the COVID‐19 pandemic, and what measures should be taken to minimize the negative effects of working from during the pandemic.

2. WORKING FROM HOME DURING THE PANDEMIC: BENEFITS, CHALLENGES, AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Working from home is not the most common practice since the usual working environment can be an office space, a factory, a school, an airport, a restaurant or somewhere else but home. Although working from home has many benefits (e.g., more flexibility, less commute, ability to continue to work during a pandemic), it also has its challenges (e.g., life and work balance, need to set up a proper workplace at home, caregiving responsibilities, mental well‐being, risk of obesity), especially during the COVID‐19 pandemic. How can we balance the benefits and disadvantages to have a better, healthier and more productive working experience for working from home during the COVID‐19 pandemic?

2.1. Working environment, ergonomics, and recommended equipment

Previous research shows that there is a strong relationship between a well‐ergonomically arranged working environment and working efficiency and health, 29 , 30 which can also be considered as non‐deteriorating health and job satisfaction. 29 An ergonomic working environment and well‐arranged physical conditions, such as appropriate temperature and low noise levels, increase employee job satisfaction and productivity. 31 It is important to use the right and ergonomic equipment, tools, and methods to prevent possible fatigue or long‐term injuries in the working environment. 32 One important factor for preventing health problems arising from the working environment is to ensure the correct posture during work. 33 Occupational musculoskeletal disorders are leading injuries arising from improper ergonomic working environments, and such disorders can have serious adverse effects on the performance and well‐being of individuals. 34 , 35 These disorders can affect the shoulder, neck, and upper extremities. 36 , 37 In addition, such disorders are traumas that do not suddenly emerge but develop gradually, and while they can disappear with short rests in early stages, it may not be possible to get rid of them in later stages even with long rests. 30 Therefore, for staying healthy and productive, it is crucial to adopt an agronomical approach while setting up the working space at home and working from home.

The most important piece of the working equipment is the ones which we spend considerable time while working. Furthermore, it may be useful to create the working environment at home as similar to the environment at the workplace as possible and to make sure that working materials, especially computers, are placed close to eye level. 36 , 38 In particular, one needs to pay attention to correctly place a computer/laptop screen to have a constant balance between head/neck and hand/wrist postures. 38 Laptops are lightweight, portable, and convenient. Besides these advantages, laptops can have cause serious health problems by allowing users to sit in poor posture positions with their compact design with an integrated display and keyboard. For example, if the screen is at the correct height, then the keyboard position becomes heightened, and when the keyboard is placed correctly, then the screen is too low. Another important component of working home is the sitting arrangement. For example, working or sitting on soft tissue areas, such as a sofa or bed, for a long‐time during working can cause individuals to feel tension and pain. An ergonomic, adjustable work chair and study desk are essential parts of office work and important for health. Pillows, towels, or cushions can be used while sitting to adjust the arms position and raise the elbow height to the tabletop level, and this would also help reducing the pressure on the hip and waist. It is also important to adjust the seat height to create a proper hip angle and achieve a “flat feet” position. If needed, proper equipment should be used to raise feet. Some new generation of desks allow height adjustment and this opens for new and more dynamic posture change possibilities during work. 38 , 39

2.2. Sleep, rest, and exercise

There is a need for adequate sleep and rest to resume working and maintaining a healthy body. 40 Sleep plays a crucial role in the physical and mental health and well‐being, and there is no better daily rest than a good night's sleep. 41 In addition, small breaks during the working day are needed to reduce fatigue, stress and tension occurred while sitting and working. 42 These will also increase productivity and affect the mood of the person positively. 42 One big disadvantage of working from home, especially with stay home calls or lockdown orders during the pandemic, is the reduction of movements of the individuals. For this reason, regular exercise becomes even more important than before during this pandemic. Regular exercise keeps the body fit and help keeping it healthy. 43 Furthermore, regular exercise helps the person to get better sleep overnight and wake‐up well rested and clearheaded. 44 At the same time, doing regular exercise helps to reduce fatigue and tension of muscles makes it easier to get ready to work. 44 , 45 Although many people have a substantial awareness of the importance of exercise in most countries, most people do not exercise. 46 Studies show that the percentage of those who do sufficient physical activity is low. 46 , 47 Therefore, family members and colleagues should encourage each other to have a sufficient sleep, to do regular exercise and to take breaks during the workday for increased productivity, improved physical health and better mental well‐being, especially during this COVID‐19 pandemic.

2.3. Work and life balance

Getting the right work and life balance is crucial and challenging not only during a pandemic but also at regular times. The COVID‐19 pandemic made it extremely difficult to attain and maintain the right level of work and life balance by forcing many employees to work from home while maintaining their family and other commitments at the same time. One challenging aspect of working from home is to separate and balance work and personal time. This is especially challenging for working parents who care for their children at the same time. These families make a significant portion of the population. In the United States, the proportion of children in the population (Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 48 ) and the proportion of both working parents are on the rise. 49 The closure of schools and childcare centers due to COVID‐19 brought an additional burden to working mothers and fathers during the pandemic. Working parents need to coordinate their working time and work activities according to their children and family life. One idea is to establish a routine for the kids and parents so that parents can get some uninterrupted amount of time for their work. Parents can take turns and schedule their time with their kids separately while giving the other parent an opportunity to focus on their work, and at the same time, they can care for their children. When possible, parents can schedule to spend more time with their kids when the kids are active and can provide their kids activities that they can do on their own at kids' quieter times. Some parents find it easier and more efficient to work very early in the mornings (before kids wake up) or late at night (after children go to bed). However, this may not be possible or even feasible for everyone due to the working hours requirement of the parents' jobs. Virtual caregivers, a new concept that many parents are not familiar with, can be a useful and important facilitator to increase productivity and efficiency for working from home. Virtual caregivers cannot change diapers or feed a baby, but they can be great for school‐age children for their education and keeping them occupied for a period of time.

One of the other challenges of maintaining a good work and life balance while working from home is to control for environmental factors and distractions at home. Making plans to prevent interruption of the working process and determining a start and end time for work is crucial. Ideally, one must separate work and personal time during the day to achieve higher work efficiency and to allocate sufficient time for personal and family matters. Although working from home make these more challenging, additional time gained by not commuting to work can be used either for work and life matters when needed. Last but not least, choosing a specific place to work at home can be useful in creating an effective and organized working environment and may help to decrease distractions.

2.4. Maintaining a good health

Maintaining good physical and mental health is crucial for one's well‐being not only during a pandemic but at all times. The pandemic situation brings additional challenges to keep physically and mentally healthy for especially those who are working from home.

The risk of obesity, hence hypertension and cardiovascular diseases, increases due to overeating when people spend an excessive amount of time at home without going out. 50 , 51 Obesity is an important public health problem in the United States, and more than 60% of the US population is overweight or obese. 52 The pandemic, less mobility and spending more time at home with easier and constant access to food may worsen this situation. To prevent gaining weight one can eliminate trans‐fatty acids in their diet and limit the consumption of sugary sodas and high‐calorie drinks. 52 In addition, one must make the necessary lifestyle changes to have a healthy and nutritious diet, and sufficient physical activity. 50 Available opportunities at home environment can be utilized in this sense. For example, a sports area, a walking area, or a hobby garden can be created, as well as activities such as cycling and walking (with physical distance requirements) can be done.

While the complete elimination of anxiety and fear is not a realistic expectation during the COVID‐19 pandemic, one needs to recognize the importance of protecting mental health and avoiding infection. The pandemic has caused fear, helplessness and anxiety in most individuals, and these emotions adversely have affected their behaviors. 53 One can be optimistic and productive under normal working conditions at regular times but they can be tired, unmotivated and nervous during a pandemic such as COVID‐19. It may be possible to reduce or eliminate such adverse effects with help of social interactions and bonds. 54 It is important to maintain daily routines while working at home such as taking a shower, getting dressed formally and having breakfast as if one leaves their home for work. Furthermore, it is essential to detach from work and not to work all the time to prevent burnout. 55 , 56 Taking virtual and real coffee breaks during work with colleagues, friends and family may be the best social activities to boost morale and refresh.

Unfavorable physical conditions, such as high temperature, high humidity, dust and noise at home can also adversely affect both the working performance and health of individuals working from home. 57 , 58 However, such risks can be reduced significantly with simple and effective measures, such as regular cleaning and ventilation of the working environment, use of noise‐canceling earbuds. 57

Waking up in the morning and going from one room to another may not drive sleep away and definitely not the best way to start a day, but walking outside, doing breathing exercises with fresh air, listening to music for a short time, having breakfast, and drinking coffee will make it easier to get ready to work.

3. POSSIBLE WORKPLACE CHANGES AFTER COVID‐19

The COVID‐19 pandemic has affected our lives profoundly in almost every aspect. Although certain companies and countries have been trying to get back to normal to reduce the economic burden of the pandemic, no one really knows what the future will bring, especially for work life. First of all, it may not be possible for people to return to their workplaces for a long time due to COVID‐19. Even if so, companies or employees may not want to work in offices due to various factors, such as profitability, productivity and comfort. Therefore, the pandemic may actually be the beginning of a change for work life. One certain change is that workplaces will not be as before. The pandemic has changed and will reshape working styles, work hours and workplace furniture by requiring and bringing the concept of social/physical distancing. Organizations should plan how to adapt to physical distancing rules and requirements and train their people accordingly. For instance, Cushman & Wakefield, 59 a real estate company, has designed an office space where employees can work two meters apart from each other. Another example is that Twitter, Facebook, Amazon, CapitalOne, Microsoft, Zillow and others have announced that they have allowed almost all of their employees to work from home for good (Twitter) or for a long time (others). 60 Furthermore, some workplaces may require their employees to work in shifts to maintain social distancing rules. Some schools have started implementing alternate day strategy for their students to have smaller class sizes and enable physical distancing rules for face to face classes as well as allowing fully remote education options for students who prefer to stay home. 61

More warning signs and symbols for physical distancing and recommended practices to reduce the spread of the Coronavirus have already been part of our lives since the beginning of the pandemic at most public spaces such as grocery stores. Now with the reopening of schools and workplaces, we will see these signs and symbols more often and especially in workplaces, government offices and almost all public spaces. Visual instructions are (and will be) placed on floors, walls, and even equipment at workplaces to remind and encourage people and employees to practice social distancing, for example, to walk at designated lanes, to prevent overcrowding at workstations and, most importantly, to maintain one‐way flow among people while walking.

In addition to signs to regulate and encourage physical distancing, we also see companies are using a greater number of products with contactless technology such as smart doors, no‐touch scanning, and facial recognition to limit employees to touch somewhere at the workplace and to reduce the potential risk of infection or spreading infection during the pandemic. We further expect most workplaces do renovations to enlarge corridors and working spaces, develop new and more strict cleaning guidelines of workplaces and to invest on new technology and equipment to decrease the spread of COVID‐19 such as proper ventilation systems, protective screens for their employees and customers, virtual meetings and work when possible.

4. CONCLUSION

The COVID‐19 outbreak continues to affect all aspects of human life such as workforce, lifestyle and life plan. 24 One of them is work from home. Working from home can provide a great level of flexibility and opportunity during a pandemic, such as COVID‐19, for those who are able to do so. Furthermore, it also helps to reduce the spread of the disease by keeping most people at home to practice physical distancing. Although working from home has many advantages, it also has its challenges. In this paper, we discuss how to reduce the negative effects and disadvantages of working from home required by the COVID‐19 pandemic, how to improve working conditions from home so that individuals are more productive and feel better by working from home, and how to decrease health issues due to working from home during the pandemic.

Many employees cannot go to workplaces during a pandemic, such as COVID‐19, and need to work from home. In such circumstances, it is crucial to develop and implement best practices for working from home to maintain a good level of productivity, achieve the right level of work and life balance and maintain a good level for physical and mental health. Also, the COVID‐19 pandemic showed that the strong infrastructure for remote work is important. Preventive studies will also need to be carried out against the problems that may arise in cybersecurity, reliability and digitalization during the pandemic. 62 Furthermore, it is expected that the world will focus on the forces of digitalization and technology after the pandemic. 63 Based on this anticipation, qualitative studies can contribute to identifying the challenges associated with working from home and the potential offer of solutions to these.

We believe that our paper is one of the first to examine the problems of an overview of working from home during the COVID‐19 pandemic, its effects on health, and recommendations to make it healthier, more productive and easier.

5. IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING PRACTICE

COVID‐19 has been one of the biggest public health and economic challenges that our world has faced. The pandemic has changed our lives in many ways significantly. One of these changes is working from home. If people can work from home productively and happily that would not only help to reduce the spread of the disease but also reduce the need for mental health services. This has a direct effect on the healthcare systems and also nursing practice. In this review, we discuss how to reduce negative effects and disadvantages of working from home during the COVID‐19 pandemic, how to improve working conditions from home so that individuals are more productive and feel better by working from home, and how to decrease health issues due to working from home during the pandemic.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

The study was conceived by Canan Birimoglu Okuyan and Mehmet A. Begen. Both Canan Birimoglu Okuyan and Mehmet A. Begen wrote and edited the manuscript.

Birimoglu Okuyan C, Begen MA. Practice Implications. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2022;58:173‐179. 10.1111/ppc.12847

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

- 1. Fadinger H, Schymik J (2020). The Effects of Working from Home on Covid‐19 Infections and Production A Macroeconomic Analysis for Germany. CRC TR 224 Discussion Paper Series, University of Bonn and University of Mannheim, Germany. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Kaplan J, Lauren F, MJ. M (2020). A third of the global population is on coronavirus lockdown—here's our constantly updated list of countries and restrictions. Business Insider.

- 3. Holly S, Woodward A (2020). About 95% of Americans have been ordered to stay at home. This map shows which cities and states are under lockdown. Business Insider.

- 4. Rossi R, Socci V, Talevi D, et al. COVID‐19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:790. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00790 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Bloom N. To raise productivity, let more employees work from home. Harvard Bus Rev. 2014;92(1/2):28‐29. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Cosgrove‐Mather B (2004). Jet Blue's Stay‐At‐Home Work Force. Retrieved from January 13. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/jet-blues-stay-at-home-work-force/

- 7. Dingel J, Eiman B (2020). How many jobs can be done at home? Covid Economics. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- 8. Boeri T, Caiumi A, Paccagnella M. Mitigating the worksecurity trade‐off while rebooting the economy. Covid Economics. 2020;(2):60‐66. https://euagenda.eu/upload/publications/covideconomics2.pdf.pdf#page=64 [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Barrot J, Grassi B, Sauvagnat J. Sectoral effects of social distancing. Covid Economics. 2020;(3):85‐102. https://cepr.org/sites/default/files/news/CovidEconomics3.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Jones F (2015. August 19). In U.S., Telecommuting for Work Climbs to 37%. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/184649/telecommuting-work-climbs.aspx

- 11. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019). Flexible benefits in the workplace. https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/factsheet/flexible-benefits-in-the-workplace.htm

- 12. Messenger J, Vargas LO, Gschwind L, Boehmer S, Vermeylen G, Wilkens M (2019). Working anytime, anywhere: The effects on the world of work. European Union and the International Labour Office. Retrieved from http://eurofound.link/ef1658

- 13. Vilhelmson B, Thulin E. Who and where are the flexible workers? Exploring the current diffusion of telework in Sweden. New Technology, Work and Employment. 2016;31(1):77‐96. [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Willis Towers Watson . (2020. March 5). North American companies take steps to protect employees from coronavirus epidemic. Retrieved from https://www.willistowerswatson.com/en-US/News/2020/03/north-american-companies-take-steps-to-protect-employees-from-coronavirus-epidemic

- 15. Alexander D (2020). BMO says 80% of employees may switch to blended home‐office work Retrieved from May 5. https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/bmo-says-80-of-employees-may-switch-to-blended-home-office-work-1.1431569

- 16. Kramer A, Kramer KZ. The potential impact of the Covid‐19 pandemic on occupational status, work from home, and occupational mobility. J Vocat Behav. 2020;119:103442. 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103442 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Bodewits K (2020). Working from home because of COVID‐19? Here are 10 ways to spend your time. Retrieved from https://www.sciencemag.org/careers/2020/03/working-home-because-covid-19-here-are-10-ways-spend-your-time

- 18. Gottlieb C, Grobovšek J, Poschke M. Working from home across countries. Covid Economics. 2020;8:22. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Rubin O, Nikolaeva A, Nello‐Deakin S, te Brömmelstroet M. What can we learn from the COVID‐19 pandemic about how people experience working from home and commuting? Working paper. University of Amsterdam: Centre for Urban Studies. 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Morgan RE. Teleworking: an assessment of the benefits and challenges. European Business Review. 2004;16(4):344‐357. 10.1108/09555340410699613 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Johnson LC, Audrey J, Shaw SM. Mr Dithers comes to dinner: telework and the merging of women's work and home domains in Canada. Gend Place Cult. 2007;14(2):141‐161. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Fonner KL, Roloff ME. Why teleworkers are more satisfied with their jobs than are office‐based workers: when less contact is beneficial. J Appl Commun Res. 2010;38(4):336. [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Fu M, Andrew J, Clinch KJP, King F. Environmental policy implications of working from home: modelling the impacts of land‐use, infrastructure and sociodemographics. Energy Policy. 2012;47:416‐423. [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Bouziri H, Smith DRM, Descatha A, Dab W, Jean K. Working from home in the time of COVID‐19: how to best preserve occupational health? Occup Environ Med. 2020;77(7):509‐510. 10.1136/oemed-2020-106599 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Alexander B, Blandin A, Mertens K (2020). Work from Home after the Covid‐19 Outbreak. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=3650114

- 26. Maruyama T, Tietze S. From anxiety to assurance: concerns and outcomes of telework. Personnel Review. 2012;41(4):450‐469. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID‐19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112934. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Odriozola‐Gonzalez P, Planchuelo‐Gomez A, Irurtia MJ, de Luis‐Garcia R. Psychological effects of the COVID‐19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113108. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113108 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. De Croon EM, Sluiter JK, Kuijer PP, Frings‐Dresen MH. The effect of office concepts on worker health and performance: a systematic review of the literature. Ergonomics. 2005;48(2):119‐134. 10.1080/00140130512331319409 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Kim JY, Shin JS, Lim MS, et al. Relationship between simultaneous exposure to ergonomic risk factors and work‐related lower back pain: a cross‐sectional study based on the fourth Korean working conditions survey. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2018;30:58. 10.1186/s40557-018-0269-1 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Morgeson FP, Humphrey SE. The work design questionnaire (WDQ): developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. J Appl Psychol. 2006;91(6):1321‐1339. 10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1321 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Madhwani KP, Nag PK. Effective Office ergonomics awareness: experiences from global corporates. Indian J Occup Environ Med. 2017;21(2):77‐83. 10.4103/ijoem.IJOEM_151_17 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Waters TR, Dick RB. Evidence of health risks associated with prolonged standing at work and intervention effectiveness. Rehabil Nurs. 2015;40(3):148‐165. 10.1002/rnj.166 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Hoe VC, Urquhart DM, Kelsall HL, Zamri EN, Sim MR. Ergonomic interventions for preventing work‐related musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb and neck among office workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:CD008570. 10.1002/14651858.CD008570.pub3 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Baydur H, Ergor A, Demiral Y, Akalin E. Effects of participatory ergonomic intervention on the development of upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders and disability in office employees using a computer. J Occup Health. 2016;58(3):297‐309. 10.1539/joh.16-0003-OA [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Balogh I, Arvidsson I, Bjork J, et al. Work‐related neck and upper limb disorders—quantitative exposure‐response relationships adjusted for personal characteristics and psychosocial conditions. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):139. 10.1186/s12891-019-2491-6 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Waersted M, Hanvold TN, Veiersted KB. Computer work and musculoskeletal disorders of the neck and upper extremity: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:79. 10.1186/1471-2474-11-79 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Abdalla S, Apramian S, Linda FC, Cullen M Occupation and Risk for Injuries. 3rd edition. Washington (DC): The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. 2017. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Schwartz B, Kapellusch JM, Schrempf A, Probst K, Haller M, Baca A. Effect of a novel two‐desk sit‐to‐stand workplace (ACTIVE OFFICE) on sitting time, performance and physiological parameters: protocol for a randomized control trial. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:578. 10.1186/s12889-016-3271-y [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Chaput JP, Dutil C, Sampasa‐Kanyinga H. Sleeping hours: what is the ideal number and how does age impact this? Nat Sci Sleep. 2018;10:421‐430. 10.2147/NSS.S163071 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Chow CM. Sleep and Wellbeing, Now and in the Future. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2883. 10.3390/ijerph17082883 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Scholz A, Wendsche J, Ghadiri A, Singh U, Peters T, Schneider S. Methods in Experimental work break research: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(20):3844. 10.3390/ijerph16203844 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Dwyer MJ, Pasini M, De Dominicis S, Righi E. Physical activity: benefits and challenges during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2020;30(7):1291‐1294. 10.1111/sms.13710 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Dolezal BA, Neufeld EV, Boland DM, Martin JL, Cooper CB. Interrelationship between Sleep and Exercise: a systematic review. Adv Prev Med. 2017;2017:1364387. 10.1155/2017/1364387 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Wan JJ, Qin Z, Wang PY, Sun Y, Liu X. Muscle fatigue: general understanding and treatment. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49(10):e384. 10.1038/emm.2017.194 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population‐based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(10):e1077‐e1086. 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. McPhee JS, French DP, Jackson D, Nazroo J, Pendleton N, Degens H. Physical activity in older age: perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology. 2016;17(3):567‐580. 10.1007/s10522-016-9641-0 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Forum on Child and Family Statistics . (2020). America's Children In Brief: Key National Indicators Of Well‐Being, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/demo.asp

- 49. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics . (2020). Employment Characteristics of Families https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/famee.pdf

- 50. Hruby A, Hu FB. The epidemiology of obesity: a big picture. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(7):673‐689. 10.1007/s40273-014-0243-x [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1966. 10.1136/bmj.m1966 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Hurt RT, Kulisek C, Buchanan LA, McClave SA. The obesity epidemic: challenges, health initiatives, and implications for gastroenterologists. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6(12):780‐792. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21301632 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 53. Ho CS, Chee CY, Ho RC. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID‐19 beyond paranoia and panic. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2020;49(3):155‐160. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32200399 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 54. Bavel JJV, Baicker K, Boggio PS, et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID‐19 pandemic response. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4(5):460‐471. 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 55. Innanen H, Tolvanen A, Salmela‐Aroa K. Burnout, work engagement and workaholism among highly educated employees: profiles, antecedents and outcomes. Burnout Research. 2014;1(1):38‐49. [ Google Scholar ]

- 56. Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):103‐111. 10.1002/wps.20311 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 57. Soriano A, Kozusznik MW, Peiro JM. From office environmental stressors to work performance: the role of work patterns. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(8):1633. 10.3390/ijerph15081633 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 58. Wolkoff P. Indoor air humidity, air quality, and health—an overview. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2018;221(3):376‐390. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.01.015 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 59. Cushman & Wakefield . (2020). 6 Feet Office. Retrieved from https://www.cushmanwakefield.com/en/netherlands/six-feet-office

- 60. Kelly J (2020. May 19). After Announcing Twitter's Permanent Remote. (2020). Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/jackkelly/2020/05/19/after-announcing-twitters-permanent-work-from-home-policy-jack-dorsey-extends-same-courtesy-to-square-employees-this-could-change-the-way-people-work-where-they-live-and-how-much-theyll-be-paid

- 61. Fantini MP, Reno C, Biserni GB, Savoia E, Lanari M. COVID‐19 and the re‐opening of schools: a policy maker's dilemma. Ital J Pediatr. 2020;46(1):79. 10.1186/s13052-020-00844-1 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 62. Gupta A. Accelerating remote workafter COVID‐19. Covid RecoverySymposium. 2020;1‐2. https://www.thecgo.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Remote-Work-Post-COVID-19.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- 63. Gasser U, Ienca M, Scheibner J, Sleigh J, Vayena E. Digital tools against COVID‐19: taxonomy, ethical challenges, and navigation aid. Lancet Digit Health. 2020;2(8):e425‐e434. 10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30137-0 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

- View on publisher site

- PDF (376.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Open access

- Published: 29 January 2022

Enforced home-working under lockdown and its impact on employee wellbeing: a cross-sectional study

- Katharine Platts 1 ,

- Jeff Breckon 2 &

- Ellen Marshall 3

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 199 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

24k Accesses

29 Altmetric

Metrics details

The Covid-19 pandemic precipitated a shift in the working practices of millions of people. Nearly half the British workforce (47%) reported to be working at home under lockdown in April 2020. This study investigated the impact of enforced home-working under lockdown on employee wellbeing via markers of stress, burnout, depressive symptoms, and sleep. Moderating effects of factors including age, gender, number of dependants, mental health status and work status were examined alongside work-related factors including work-life conflict and leadership quality.

Cross-sectional data were collected over a 12-week period from May to August 2020 using an online survey. Job-related and wellbeing factors were measured using items from the COPSOQIII. Stress, burnout, somatic stress, cognitive stress, and sleep trouble were tested together using MANOVA and MANCOVA to identify mediating effects. T-tests and one-way ANOVA identified differences in overall stress. Regression trees identified groups with highest and lowest levels of stress and depressive symptoms.

81% of respondents were working at home either full or part-time ( n = 623, 62% female). Detrimental health impacts of home-working during lockdown were most acutely experienced by those with existing mental health conditions regardless of age, gender, or work status, and were exacerbated by working regular overtime. In those without mental health conditions, predictors of stress and depressive symptoms were being female, under 45 years, home-working part-time and two dependants, though men reported greater levels of work-life conflict. Place and pattern of work had a greater impact on women. Lower leadership quality was a significant predictor of stress and burnout for both men and women, and, for employees aged > 45 years, had significant impact on level of depressive symptoms experienced.

Conclusions

Experience of home-working under lockdown varies amongst groups. Knowledge of these differences provide employers with tools to better manage employee wellbeing during periods of crisis. While personal factors are not controllable, the quality of leadership provided to employees, and the ‘place and pattern’ of work, can be actively managed to positive effect. Innovative flexible working practices will help to build greater workforce resilience.

Peer Review reports

The Covid-19 pandemic, and subsequent public health lockdowns around the world, have precipitated a shift in the working practices of millions of people. An estimated 47% of the British workforce reported to be working at home in April 2020 (compared to 5% in 2019), with 86% of this number a direct result of the Covid-19 national lockdown [ 1 ].

Home-working, or ‘home-based telework’ as it is sometimes termed [ 2 ], has traditionally been undertaken by mutual agreement between employer and employee, typically in white-collar and professional occupations. Most of what is known about the impact of home-working on employees is in the context of voluntary and consensual arrangements, such as flexible working schedules and hybrid arrangements where time is shared between remote telework and office-based work. How a sudden and unexpected change in working circumstances impacts the psychological, emotional, and physiological wellbeing of workers is not well understood, and yet there is broad consensus that positive employee wellbeing is an important precursor to positive performance at work [ 3 ].

Conceptualization of wellbeing at work

Work-related wellbeing as characterised by Van Horn et al. [ 4 ] comprises the five interrelated dimensions of affective wellbeing (mood/affect, job satisfaction, organisational commitment, emotional exhaustion); cognitive wellbeing (cognitive weariness, concentration and taking up new information); social wellbeing (social functioning in relationships with colleagues); professional wellbeing (autonomy, aspiration, and competence); and psychosomatic wellbeing (physical health). This multi-dimensional approach provides a broader frame of reference to help understand the organisational and job-related factors that influence personal wellbeing. Though focused on the individual, these constructs are important to employers who must ensure that gains are not achieved at the cost of poor employee health outcomes [ 5 ].

Wellbeing in a home-working context

Experience of home-working will differ from population to population. While many studies have supported the view that home-working engenders positive health outcomes such as reduction in stress [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ], burnout [ 10 ] and fatigue [ 11 , 12 ], as well as increases in general happiness [ 11 ] and quality of life [ 8 , 13 ], others have found detrimental impacts to general psychological wellbeing [ 14 , 15 ], burnout [ 16 ], and work-life balance [ 17 , 18 ]. Nevertheless, the mechanisms driving these effects are not always clear and are dependent upon a range of individual and environmental factors. Gender and parental status, for example, play key roles in the nature and experience of working at home, as this arrangement tends to promote a more traditional division of labour, with women often using home-working as a tool to maintain work capacity in periods of increased family demands, such as after childbirth [ 19 ].

Flexible working arrangements, including working at home, that increase employee autonomy and choice are generally found to be conducive to positive wellbeing [ 20 ] and may help improve work-life balance. Flexible working arrangements are more accommodating of individual needs and allow for greater employee independence, higher levels of work-time control and agency over work-related decisions (autonomy), yet are associated with significantly higher levels of work-life conflict [ 21 ], where work concerns distract from and disrupt home life (or vice versa) wherein stress is induced or increased and efforts at sleep and recovery are hampered [ 22 , 23 ].

The elimination of choice – transitioning to a an ‘enforced’ home-working scenario

Inquiry into whether what is known about home-working under ‘normal’ circumstances holds true when the element of personal choice is removed, and the worker may have to share space and resources with other household members mandated to stay at home under lockdown.

Recent research suggests that mandated home-working environments may have negative impacts from a physical health perspective [ 24 ], that the persistent overuse of technology for communications is increasing levels of stress [ 25 ], and the social deficit created by lack of interpersonal contact while working at home under lockdown may be detrimental to emotional wellbeing [ 26 ]. Some have suggested that work-life conflict is exacerbated in an environment where the boundaries between work and home are permeable and ill-defined, in particular at a time when leaving the home for long periods of time is not possible, such as during lockdown [ 18 ]. For employees managing long-term mental health conditions, working at home during lockdown is likely to have had serious negative consequences, as routines are disrupted and access to critical support services and social contact are lost [ 27 , 28 ].

Female employees may be more at risk of emotional exhaustion and physical health problems under lockdown circumstances than male employees [ 29 , 30 ], and increased autonomy, such as the ability to adjust working times and work overtime to catch up on work at home, has a particularly detrimental impact on women due to increased work-life conflict [ 31 ]. Women, and those of both genders in younger age groups (< 35 years), more often report high emotional demands at work and physical exhaustion during periods of mandated home-working [ 32 ].

Quality of leadership, supervisory and collegial support all influence employee experience, yet in a time of crisis such as the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown, organisational leaders may not be properly equipped to manage their people from a distance, lacking the essential skills of effective ‘virtual leaders’ [ 33 , 34 ].

Aims of this study

This study examined the combined impact of age, gender, dependants, mental health status and work status in relation to enforced home-working and the effects on wellbeing markers including stress, burnout, depressive symptoms, and sleep in UK employees. The study considered the following across public, private and third sector organisations; (i) which groups have the poorest wellbeing levels at a time of mandated home-working and (ii) which factors exert significant moderating and mediating influences; both in terms of personal and environmental factors such as gender, age and dependants, and work-related factors such as quality of leadership and social support.

Participants and procedures

Ethical approval for the study was obtained via Sheffield Hallam University Research Ethics Committee (No. ER23891582). Private, public and third sector organisations operating in the United Kingdom were invited to participate in the study. Participating organisations were required to have a significant proportion of their workforce involuntarily working from home due to Covid-19 pandemic lockdown measures. Nine organisations volunteered to participate, with private ( n = 5), public ( n = 2) and third sector ( n = 2) organisations represented in the sample. A total of 623 adults from these organisations responded to an invitation to participate delivered via their employer. Individual participant inclusion criteria included being of working age (18 years +) and in either full-time or part-time employment. A summary of participant demographics can be found in Table 1 .

Data collection and measures

Cross-sectional data were collected over a 12-week period from May 2020 to August 2020 during the first wave of Covid-19 pandemic lockdown measures in the UK. A 33-item questionnaire was developed for the purposes of the study and delivered online using Qualtrics secure web-survey (© Qualtrics LLC, 2021). Informed participant consent was collected on the Qualtrics platform prior to data collection, and those that did not consent were not able to access the survey.

Five demographic items were collected: age category, gender, number of dependants, mental health status (defined in two categories as presence or absence of diagnosed mental health condition), and work status (defined in four categories as working at home full-time, working at home part-time, working in usual place of work, furloughed).

Job-related and health and wellbeing factors were measured using 28 items from the English version of the Third Copenhagen Psychosocial Risk Assessment Questionnaire (COPSOQIII) [ 35 ] comprising core items plus additional items from the middle and long version as appropriate. The COPSOQIII was deemed appropriate for the study due to its effectiveness across diverse industry sectors and in organisations of varying sizes, and for allowing analysis against different workplace wellbeing frameworks including the Five-Dimension Model [ 4 ].

Work-related factors in six domains were investigated by assessing to what extent respondents were able to exert control over breaks (1 item), extent of overtime worked (1 item), how they rated quality of organisational leadership (2 items), how they rated social support from their supervisor and colleagues (2 items) and level of work-life conflict experienced (4 items). Work-related items were measured on a 5-point rating scales using various statements appropriate to the question.

Wellbeing factors in six domains were investigated by assessing to what extent the respondent suffered from common symptoms. The domains were sleeping troubles (1 item), burnout (4 items), stress (3 items), somatic stress (3 items), cognitive stress (3 items) and depressive symptoms (4 items). Wellbeing items were measured on a 5-point rating scale (scored as 100 = all the time, 75 = a large part of the time, 50 = part of the time, 25 = a small part of the time, 0 = not at all). All wellbeing subscales showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s \(\alpha >0.8\) ) but the two items from the ‘control over working time’ subscale (control over breaks and extent of overtime worked) had poor consistency and were therefore used separately in analysis.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses of data were undertaken using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Version No. 26) Stress, burnout, somatic stress, cognitive stress and sleep trouble were all at least moderately correlated and demonstrated similar impact so were tested together using MANOVA initially and then MANCOVA to test mediating effects, all with Tukey post-hoc tests; whereas group comparisons for depressive symptoms were not consistent and were tested separately for all analyses.

A standardised factor score to represent ‘overall stress’ (alpha = 0.87) was created from the stress-related subscales stress, burnout, somatic stress, cognitive stress, and sleep trouble, and used instead of the individual variables. Initial analysis used independent t-tests and one-way ANOVA to test differences in overall stress, for each of the key demographic variables. Regression trees were used to identify groups with higher levels of the stress factor score or depressive symptoms using the core demographic variables of interest and the key work-related factors of quality of leadership, social support, and work-life conflict.

A total of 623 people completed the survey (62% female). 53% of all participants had one or more dependants, while 11% reported a diagnosed mental health condition. The majority (81%) were working at home because of lockdown restrictions, either full-time or part-time, while 9% continued to work in their usual place. 5% of participants were furloughed and so did not complete all the questions from the work-related subscales. 5% of people defined their work status as ‘other’ and were removed from analyses where work status was considered.

Gender, age, mental health status, dependants and work status effects on wellbeing markers and work-life conflict

As shown in Table 1 , women had significantly higher levels of stress and depressive symptoms (t = -3.06, p = 0.002; t = -4.19, p < 0.002), but men reported significantly higher levels of work-life conflict (t = 2.31, p = 0.021). Across both genders, those aged 25–44 years had significantly higher stress compared to those aged 45 + years ( F = 8.98, p < 0.001). Depressive symptoms decreased with age, with those aged 16–24 years reporting the highest levels, and those aged 45 + years reporting lower levels than all other age groups. The 35–44 age group reported significantly higher levels of work-life conflict than those aged < 25 years or 45 + years of age ( F = 4.9, p = 0.001). Those who reported a diagnosed mental health condition had significantly higher stress and depressive symptoms than those who did not (t = -7.5, p < 0.001; t = -5.7, p < 0.001), but no significant difference in work-life conflict was found between these two groups. The number of dependants did not impact on depressive symptoms, but stress variables were found to be consistently higher for those with two dependants ( F = 4.24, p = 0.006). Levels of work-life conflict were significantly higher for those with two dependants when compared to the effects of 0, 1, or 3 + dependants ( F = 15.8, p < 0.001).

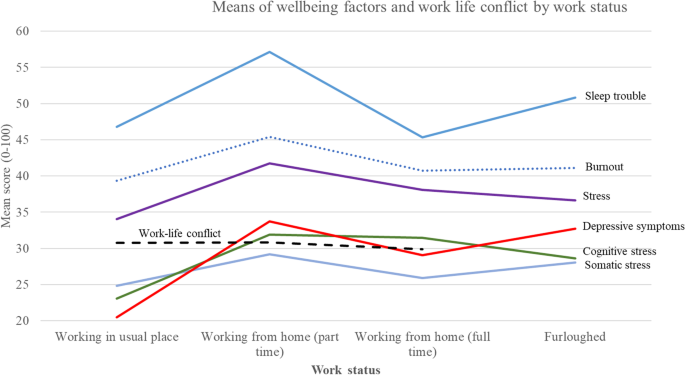

As shown in Fig. 1 , those working at home part-time generally had the highest levels of stress and depressive symptoms. There were significant work status differences for sleeping troubles ( F = 5.32, p = 0.001), with those working at home part-time having significantly higher levels of sleep troubles than those working at home full-time. Those working at home full-time or part-time, and those furloughed, had significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms than those working in their usual place of work ( F = 3.94, p = 0.009).

Wellbeing factors and work life conflict by work status

Work status and mental health

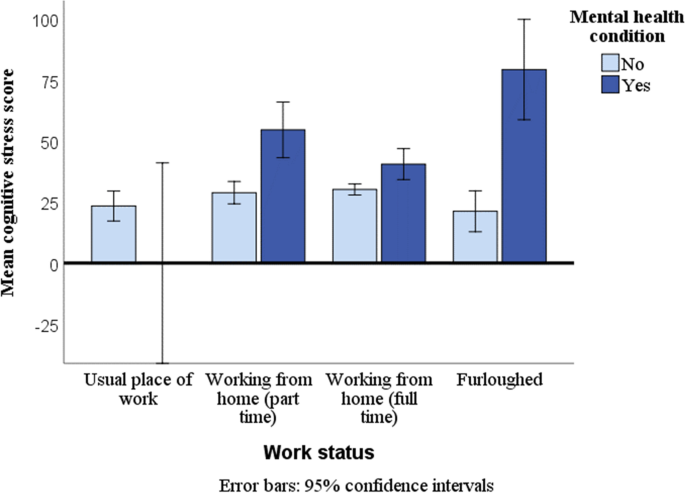

There was a significant interaction between work status and mental health [Wilk's Λ = 0.935, p = 0.002, \({{\eta }_{p}}^{2}=0.022]\) for the stress-related variables, and for depressive symptoms [ F (3,534) = 3.35, p = 0.019, \({{\eta }_{p}}^{2}=0.018]\) . Those with a diagnosed mental health condition had consistently higher levels of stress, cognitive stress, somatic stress, burnout, and sleep troubles when working at home or furloughed. Within this group, part-time home-workers and those who were furloughed experienced the highest levels stress and depressive symptoms (see Fig. 2 as a typical example), although the differences were not significant for depressive symptoms.

Mean cognitive stress (marginal) by work status and mental health status. 95% Confidence Intervals

Combined effects of work status and gender

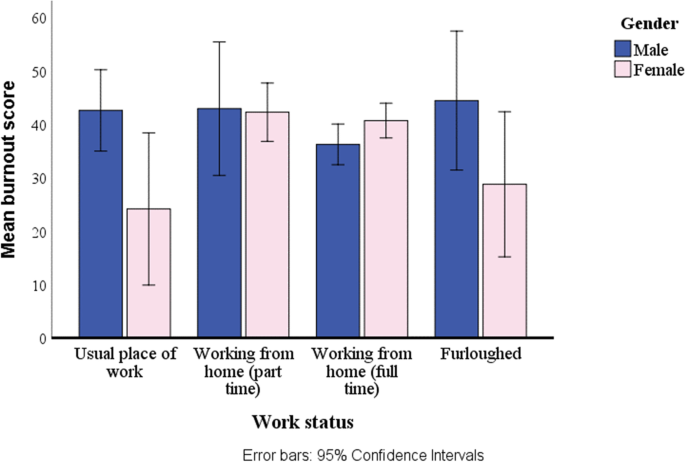

The combined effects of work status and gender were only examined for the group with no diagnosed mental health condition. The interaction was significant between work status and gender for stress [Wilk's Λ = 0.935, p = 0.007, \({{\eta }_{p}}^{2}=0.022]\) . As shown in the example in Fig. 3 , work status generally had more of an impact on women, with those working at home, particularly part-time, having consistently higher scores on the stress variables. For those in their usual place of work, men scored significantly higher than women for stress and burnout.

Burnout by work status and gender

Quality of leadership was a significant negative predictor of stress, burnout, somatic and cognitive stress for both men and women [Wilk's Λ = 0.959, p = 0.003, \({{\eta }_{p}}^{2}=0.041]\) . After controlling for quality of leadership, the interaction between gender and work status for stress was still significant [Wilk's Λ = 0.951, p = 0.015, \({{\eta }_{p}}^{2}=0.025]\) but the place-of-work differences observed for women were reduced, so quality of leadership was not a mediating factor.

After controlling for work-life conflict, the interaction between gender and work status for stress was significant [Wilk's Λ = 0.953, p = 0.017, \({{\eta }_{p}}^{2}=0.024]\) ], and gender differences increased as men had higher work-life conflict scores generally. For those working full-time at home, women had significantly higher stress, burnout, somatic stress, and sleep trouble than men after controlling for work-life conflict. Women working at home part-time had significantly higher stress scores than men, and women in their usual place of work had significantly higher levels of sleep troubles. No significant interactions were found between work status and gender for depressive symptoms.

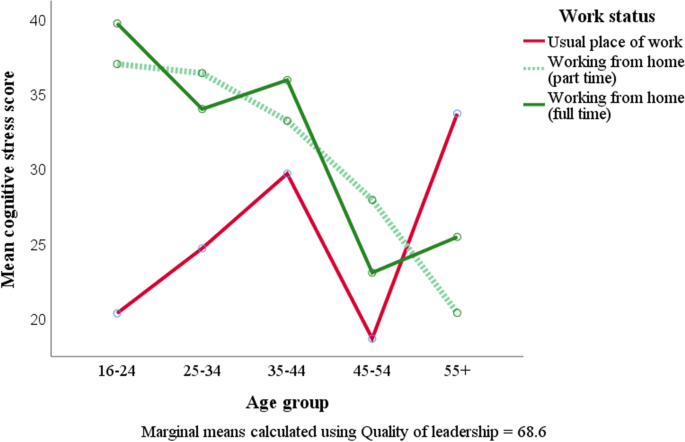

Combined effects of work status and age

The interaction between work status and age group for stress-related factors was significant (Wilk’s lambda = 0.848, p = 0.037, \({{\eta }_{p}}^{2}=0.034\) ) for the group with no diagnosed mental health condition, with age impacting most on part-time home-workers, and those in the 35–44-year age group most stressed. After controlling for quality of leadership, differences became more pronounced and a more general downward trend by age group was observed – particularly for somatic and cognitive stress (Fig. 4 ). No significant interactions were found between work status and age for depressive symptoms.

Cognitive stress by work status and age group

Combined effects of work status and number of dependants

The interaction between work status and number of dependants for stress was not significant so was removed from the model. The interaction between work status and number of dependants for depressive symptoms was borderline significant [F(9,466) = 800.9, p = 0.054,, \({{\eta }_{p}}^{2}=0.035\) ]. Those with one dependant whilst working at home full-time or part-time had significantly higher levels of depressive symptoms than those in their usual place of work. Those with 3 + dependants and on furlough leave experienced significantly more depressive symptoms than those in their usual place of work.

Identifying groups of workers with highest and lowest levels of depressive symptoms or stress.

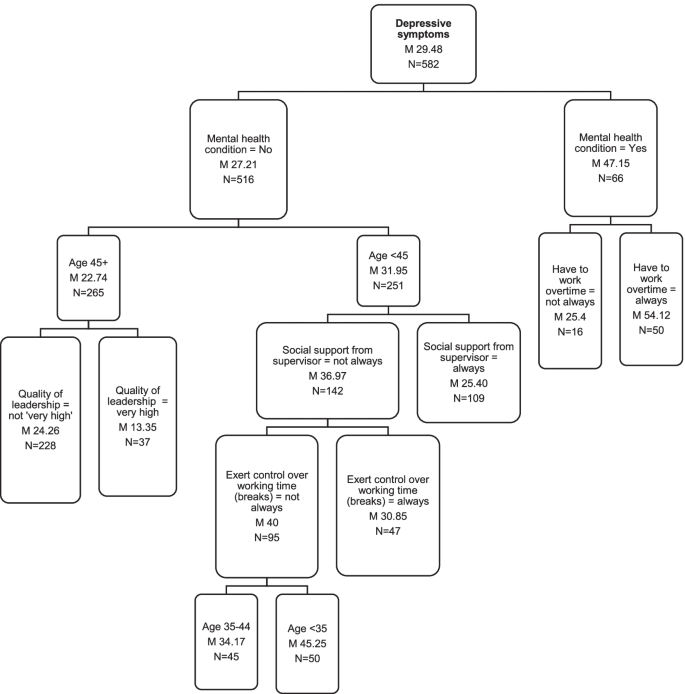

Regression tree analysis enabled further groupings to be identified from a wider range of variables. Figure 5 shows the regression tree with depressive symptoms as the dependent variable and all key demographic and work-related factors included. The presence or absence of a mental health condition gave rise to the largest difference in mean level of depressive symptoms (20-point difference), so the groups were separated first. Those with an existing mental health condition who occasionally or always worked overtime were the most depressed group (M 54.1, 95% CI 47,61). Those with a mental health condition who never worked overtime had a much lower score for depressive symptoms (M 25.4, 95% CI 14,37) which is more in line with the group with no mental health condition (M 27.2).

Comparison of wellbeing and work-related factor means by depressive symptoms regression tree group (M = mean score 0–100)

Amongst those with no mental health condition, the sub-group with the lowest depressive symptoms overall was the one aged over 45 years who rated quality of leadership highly (M13.35, 95% CI 9,18), and the sub-group with the highest levels of depressive symptoms overall were those aged under 35 years, who didn’t always have social support from their supervisor and could not always exert control over taking breaks (M 45.3, 95% CI 39,52).

Ten sub-groups were identified using the standardised stress factor score as the dependent variable which has a mean of zero; thus, positive scores were above average and negative scores were below average. Table 3 shows the group means for each of the stress variables as well as the standardised score for each group. The presence or absence of a mental health condition gave rise to the largest difference in mean level of stress, so those groups were separated first. Mean stress levels were highest overall in the sub-group with diagnosed mental health conditions that always had to work overtime (M 1.16, 94% CI 0.89,1.42). For the group with no mental health condition, the key variables selected to separate groups were quality of leadership, age, control over breaks, number of dependants and gender. Where quality of leadership was low (M < 69), the group with the highest mean levels of stress were those aged 25–44 (M 0.41, 95% CI: 0.21,0.62). Where quality of leadership was high (M 69 +) the group with the highest levels of stress had 2 + dependants and were less able to exert control over breaks (M 0.57, 95% CI: 0.15,1). This sub-group also had the highest levels of burnout, somatic stress, and sleep trouble. The sub-group with the lowest levels of stress were those aged under 25 or 45 + who had high levels of control over their breaks and zero dependants (M -0.97, 95% CI: -1.3,-0.64). This group also had the lowest levels of burnout, somatic stress, cognitive stress and depressive symptoms and relatively high levels of social support.

Employee wellbeing has been impacted by the recent global pandemic, typically resulting from increased levels of enforced home-working. This study set out to examine the impact of age, gender, dependants, mental health status and work status on employee wellbeing under enforced home-working conditions, as well as the influence of work-related factors such as work-life conflict, quality of leadership and social support from supervisors and colleagues.

The findings suggest that detrimental wellbeing impacts of enforced home-working are most acutely experienced by those with existing mental health conditions, regardless of age, gender, or work status, and that home-working and having to work regular overtime strongly exacerbate issues of poor sleep, stress, and depression in those who are suffering with mental health issues. In healthy individuals, both age and gender appear to play moderating roles in feelings of stress and depression at times of enforced home-working, with women and younger age groups generally faring worse than others.

Working pattern and place (‘work status’) has emerged [ 36 ], alongside the presence of a mental health condition, as a key factor in determining wellbeing impacts of enforced home-working, with place and pattern of work having a greater impact on women. Those working at home full- or part-time reported significantly higher levels of stress and depression than those who continued to work in their usual place during lockdown, indicating that abrupt disruption to routine and unfamiliarity of working practices and environment, potentially coupled with job insecurity and concerns about the pandemic in general, has a broadly negative effect on emotional wellbeing.

Quality of leadership and social support from colleagues also play key roles in moderating wellbeing outcomes, with leadership quality particularly influential in mental health outcomes for younger age groups. Poor organisational leadership and the requirement to work after hours are known to be significantly associated with occupational stress, anxiety, and depression [ 37 , 38 ] and for those with mental health issues these factors appear amplified; indeed, where regular overtime is not required, the positive impact on depressive symptoms in this cohort is considerable. Where leadership quality was rated highly in the present study, it had a positive impact by reducing stress and depressive symptoms in those working at home full-time with a diagnosed mental health condition. This reinforces the critical role organisational leaders play in mitigating any damaging effects of home-working in those suffering poor mental health, and thus should be a priority for organisations.

Any individual may suffer altered mood states on a short-, medium- or long-term basis which are experienced as depressive symptoms, stress, and poor sleep, as has been the case for much of the global population during the Covid-19 pandemic [ 39 ]. In the UK, around 1 in 5 adults reported feelings of depression in early 2021 – over double pre-pandemic levels [ 40 ]. In the present study, leadership quality impacted across several healthy groups and influenced the extent to which employees experienced stress, depressive symptoms and trouble sleeping. For example, leadership quality strongly influenced experience of depressive symptoms in employees aged 45 + , with those experiencing ‘very high’ leadership quality suffering virtually no depressive symptoms at all, compared to those who were not. This evidence suggests that the most important protective factors against stress and depressive symptoms were not having an existing mental health condition and high quality of leadership, the latter of which may act, for example, as a buffer against the stresses of a lack of work resources [ 41 ].

The role of gender and work status on mental health

Women’s psychological health appears to have been deeply affected by the pandemic [ 42 ]. Women have suffered significant and clinically relevant declines in mental wellbeing [ 39 ] alongside generally higher levels of health anxiety [ 43 ]. Evidence from this study shows that women suffered higher levels of stress, burnout, somatic stress, sleep trouble and depressive symptoms than their male counterparts during lockdown, particularly when home-working on a part-time basis, while men reported higher levels of work-life conflict.

As many organisations consider a move to permanent remote-working or ‘hybrid’ working models in the wake of the pandemic, they must be appropriately sensitive to the mental health challenges this may bring about for working women. Approximately 70% of the British national part-time workforce are women (some 5.67 million women in Q1 2021) [ 44 ] and the choice of many women to work part-time appears to be connected to childcare responsibilities [ 45 ]. Childcare and housework responsibilities remain predominantly within the remit of the mother (in households with children), with women in part-time work spending more time on house-work and childcare than those in full-time work [ 46 ]. Women working from home during lockdown with no access to supportive childcare are especially exhausted [ 42 ]. It is feasible that long periods of involuntary part-time home-working, such as that which could be imposed via a ‘hybrid’ model, could results in increased poor health outcomes for women as they struggle to balance domestic and professional responsibilities.

The impacts of enforced (often abrupt) new working patterns and practices appear to be equally felt by men. Working parents in general have higher levels of stress [ 47 ] and work-life conflict [ 48 ], and this study found that overall stress was significantly higher for individuals of either gender with two dependants (compared to 0,1, or 3 + dependants), although no impacts on depressive symptoms were found. Therefore, while women report more negative psychosomatic wellbeing effects, men appear to experience the greatest disruption under lockdown, reporting the highest levels of work-life conflict while home-working – which was itself observed to have a strong positive relationship with stress. This finding is somewhat unexpected and suggests that women are in some way better prepared to manage disruptions to their working life than men, which may be due to persisting traditional gender and parenting roles. The presence of dependants at home and age of dependants will influence stress-related issues [ 48 ], so in the absence of physical or temporal boundaries between work and home life, how effective an individual is at managing their transition between work and non-work activity whilst home-working may strongly influence the level of work-life conflict they experience [ 49 ], regardless of gender.

The influence of age and work status on mental health

For young adults in the UK, experience of depressive symptoms more than doubled during the pandemic, with 29% of those aged 16–39 reporting symptoms in early 2021 [ 40 ]. The reasons underpinning this wave of poor mental health are complex, but loneliness, work uncertainty, and financial insecurity are all indicated as factors that have amplified feelings of depression and sadness in young people during the pandemic [ 49 , 50 , 51 ].

For individuals without diagnosed mental health conditions, age emerges in this study as the key variable in determining level of depression and stress during periods of enforced home-working, with symptoms of both decreasing with age. After controlling for quality of leadership, differences between age groups became more pronounced and a downward trend by age was observed – particularly for somatic and cognitive stress. With poor ‘ cognitive wellbeing’ [ 4 ] comes lack of concentration, weariness, and burnout [ 52 ], yet a simple change in schedule may decrease the likelihood of job stress by 20% and increase job satisfaction [ 53 ] providing further evidence of the importance of competent and ‘health promoting’ leadership to maintain both positive wellbeing [ 54 ] and work engagement.

Professional isolation and lack of contact and communication with colleagues will negatively affect mental wellbeing in times of home-working during a crisis [ 55 , 56 ]. In this study, those under 35 without a pre-existing mental health condition who had low levels of support from supervisors (and no control over breaks) were found to have the highest levels of depressive symptoms, while those aged over 45 who rated leadership quality highly were the least depressed group in this study. While older age groups may be suffering less, they appear more willing to seek help and support with serious illness than their younger counterparts [ 57 ], which may make identification of arising issues more difficult. These findings further emphasize the importance of factors such as autonomy and relationships associated with the ‘ social’ and ‘ professional’ dimensions of wellbeing [ 4 ], and directs organisations to encourage employees to develop regular, meaningful social contact with peers and supervisors; but equally be supported to psychologically detach from work and draw firm boundaries between their work and domestic domains.

Implications for practice

There is a need to adapt approaches to leadership (and its training) that embrace the differences between home-working and traditional office-based environments and the challenges of ‘virtual’ leadership. It does not seem viable to rely on typical approaches to leadership and management that do not have currency and flexibility in the future work context. Organisations must invest in manager training and adopt a style of virtual leadership that is supportive and empowering (not intrusive or exploitative) alongside clear referral pathways for those needing more professional mental health support. This also raises the opportunity of increasing managers awareness of wellbeing in the workplace, its impact, and strategies for alleviating ill-health and enhancing wellbeing.

Limitations and future research

Working practices, especially for office-based individuals, are forever-changed. There is a need for research to consider the unique and varied contexts within which employees now work and to apply a range of quantitative and qualitative methods to understand both the ‘what’ and ‘why’ of home-working and its impact on individuals using validated tools [ 58 ].

A cross-sectional survey design was chosen for this study due to the ease and speed of implementation in a pandemic context, however the limitations of this design are acknowledged, as is the risk of sampling and survey bias. Though efforts were made to limit this, the analysis is susceptible to random statistical error due to sample size. Equally, the homogenous geographical location of participants must be considered. Nevertheless, this study provides critical insights and direction for future research, which must consider the mediators and moderators of employee wellbeing across larger and geographically diverse groups and provide frameworks for organisations to monitor and evaluate the effect of the workplace, be that office-based, or a blend of both.

Employee experiences of enforced home-working are influenced by factors such as personality, home environment, access to social support, physical and mental health issues, employment support structures and financial status. Yet, perhaps the most important factor that can be controlled and better managed by organisations is the quality of leadership provided to employees. The Covid-19 pandemic has forced employers to rethink their approach to how, where and when their employees work but the awareness of the need for adapting leadership styles, processes and mechanisms appears to be lagging. There is a need to better understand the factors that positively and negatively influence employee wellbeing and take a more proactive and preventative approach to improving employee outcomes through policy development, manager training and creative health interventions. While the pandemic will pass in time, organisations must consider the impact of future crises on their flexible working practices to build greater resilience in systems and employees. While personal employee factors are not controllable, organisations must develop a greater understanding of the role they play in reducing the likelihood of ill-health and promoting increased wellbeing and subsequently morale and productivity.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are held within Sheffield Hallam University Research Store and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ONS: Coronavirus and homeworking in the UK: April 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/coronavirusandhomeworkingintheuk/april2020 (2020). Accessed 1 March 2021.

Eurofound and the International Labour Office: working anytime, anywhere: the effects on the world of work. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg and the International Labour Office, Geneva. 2017. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef1658en.pdf . Accessed 1 March 2021.

Taris TW, Schaufeli WB. Individual well-being and performance at work: a conceptual and theoretical overview. In: van Veldhoven M, Peccei R, editors. Well-being and performance at work: the role of context. London: Psychology Press; 2015. p. 24–43.

Google Scholar

Van Horn JE, Taris TW, Schaufeli WB, Schreurs PJG. The structure of occupational well-being: a study among Dutch teachers. J Occup Organ Psychol. 2004;77(3):365–75. https://doi.org/10.1348/0963179041752718 .

Article Google Scholar